They say…

Best beer and travel writing award 2015, 2011 -- British Guild of Beer Writers Awards

Accredited Beer Sommelier

Writer of "Probably the best book about beer in London" - Londonist

"A necessity if you're a beer geek travelling to London town" - Beer Advocate

"A joy to read" - Roger Protz

"Very authoritative" - Tim Webb.

"One of the top beer writers in the UK" - Mark Dredge.

"A beer guru" - Popbitch.

|

European Beer Bloggers Conference 2011

ABV: 8.15%

Origin: Stabio, Ticino, Switzerland

Website: www.badattitude.ch

Birrificio Ticinese Bad Attitude Two Penny Porter Yes, another brewer with a bad attitude, this time explicity proclaimed, and hailing from well-behaved Switzerland, though from the Italian speaking region, within a stone’s throw of the Italian border. Brewer Roberto Bianchi creates the beers at the Ticinese brewery, which also produces the San Marino brands, though I’m not clear about the relationship between them — contract, brewery share or just separate families of beers [Since writing this, Swiss-based beer writer Laurent Mousson has clarified the situation — see his comment below]. Lavishly illustrated labels and publicity materials feature appropriate grafitti and collage artwork with ransom note lettering — strange how today’s bad boys are still borrowing from the rebellious imagery of 35 years ago.

Bad Attitude hit the news last year as the first European brewery to produce craft beer in cans, following US models like Oskar Blues and Maui, but this sample was bottled, and bottle conditioned too. The beer is inspired by British porter — the union flag on the label isn’t just for punk cred — and refers in its name to 18th century London beer prices, but I wouldn’t rely too much on the historical credentials. The roasted malt may be British but the hops — Amarillo, Chinook and Willamette — are decidedly transatlantic.

It’s a very dark brown beer, near black, with a nice foamy beige head and a slightly chocolatey, malty aroma with a light hint of exotic spice. The palate is dark with chocolate and pencil lead flavours, very slightly acidic and tangy but also very creamy with notably burry, coffeeish hops lending a definite bitterness. Tangy fruit starts a long finish which develops hints of mint before ending with plenty of burnt, ashy roasted malt character. Overall a stylish, flavourful and imaginative twist on the style.

This was one of the beers featured at the Live Beer Blogging session at the Beer Bloggers Conference — but I confess I forewent my laptop for my old fashioned notebook and pencil.

Read more about this brewerys’ beers at ratebeer.com: http://www.ratebeer.com/brewers/birrificio-ticinese-sa/2853/

European Beer Bloggers Conference 2011

ABV: 8.2%

Origin: Dunbar, East Lothian, Scotland

Website: http://www.innisandgunn.com/

Innis & Gunn Oak Aged Beer Scotland’s Innis & Gunn specialises in oak ageing beer — “like no other beer”, they’ve been known to claim rather inaccurately, although their take on the process is unusual. It came about when Dougal Sharp, then brewer at Caledonian, was asked to create a beer purely for seasoning barrels destined for whisky production. It was never intended for consumption, but Dougal noticed it being enjoyed by distillery staff. Innis & Gunn followed in 2003 as what was almost certainly the UK’s first commercially marketed oak matured beer. I&G is a beer firm rather than a brewer, mainly commissioning from Greene King subsidiary Belhaven, though they’re also now contracting to Tennent Caledonian’s Wellpark brewery in Glasgow. Bottled beers aren’t bottle conditioned.

I confess I’ve never been a great fan of I&G, finding its flagship products rather soft and sickly, so this beer came as a very pleasant surprise. Canada is an important export market for the company, thus these strong specials which first appeared a few years back to mark Canada Day/Fête du Canada on 1 July. At first they were matured in Canadian oak but this 2011 version, presented at the Live Beer Blogging session of the Beer Bloggers Conference, uses bourbon oak and is hopped with Fuggles.

A reddish beer with a cherry tinge and a light bubbly head, this has an inviting, definitely casky wood aroma with a smokey bourbon note and a touch of cheese. As usual with I&G the palate is sweetish but very minty, fresh and spicy, quite unusual with a very well balanced mix that includes spiced orange and notes reminiscent of coriander, though to my knowledge none is added. A lightly spicy, toasty finish continues the slight minty tone, with a touch of charcoal. Definitely the best I&G I’ve tried and also popular with my fellow tasters.

Read more about an earlier version of this beer at ratebeer.com: http://www.ratebeer.com/beer/innis-gunn-limited-edition-canadian-cask-oak-aged-beer-bottle/103719/

European Beer Bloggers Conference 2011, Top Tastings 2011

ABV: 4.5%

Origin: Nynäshamn, Södermanland, Sweden

Website: www.nyab.se

Nynäshamns Bedarö Bitter One of the highlights of the Beer Bloggers Conference was a Night of Many Beers hosted by Camden Town brewery, most of which I spent hovering by the table of Swedish and Italian craft beers which were nearly all new to me. The Swedish selection proved particularly alluring, especially since two of the brewers represented were there in person. But my pick of those I tried was this very memorable and remarkable beer, one of those brought along by Swedish-based blogger and industry figure Darren Packman of Beer Sweden, who described it as a modern Swedish classic.

It’s certainly done well in its home territory. It was the first brew to emerge from this microbrewery at Nynäshamn, on the coast near Stockholm, when it opened in 1997 — Bedarö is the name of a nearby island — and went on to win numerous awards including Best Swedish Beer at the Stockholm Beer Festival in 2006. It’s proved so popular in the country’s Systembolaget shops — the state controlled monopoly on alcohol sales — that since 2009 it’s been stocked in all of them. An unpasteurised beer made from British pale, crystal and wheat malts from Fawcetts, and Chinook and Cascade hops, it’s intended as an interpretation of an Extra Special Bitter but is very distinctive in its own right.

This deep gold beer has a light yellow foamy head and a spicy aroma with plenty of citrus and an oily note that for some reason made me think of pilchards. That fishy, though not at all unpleasant, quality — maybe it’s the Scandinavian associations at work in my brain here — persists into a sweet, spicy and also slightly oily palate that rapidly develops lovely fruit flavours too. I noted redcurrants and blackcurrants, peaches and spicy retronasals in unusual combination. After the sparkling complexity of the palate, the finish is satisfyingly soothing, with a nice bite of pippy, peppery hops turning slightly powdery and pursing on the tongue. Highly distinctive and well deserving of its success.

Read more about this beer at ratebeer.com: http://www.ratebeer.com/brewers/nynashamns-angbryggeri/1067/

European Beer Bloggers Conference, London, May 2011 What low horizons we Europeans sometimes have. When I first got an email inviting me to the first ever European Beer Bloggers Conference, my first thought was that it must be a joke or a scam. Not that I thought European beer bloggers were unworthy of being dignified with something as important and grand-sounding as a conference, I just didn’t expect this importance to be recognised by anyone with the resources to organise such an event. Then I spotted the name of Mark Dredge, one of the top UK beer bloggers, a fine writer who has also always struck me as a sensible fellow, which convinced me to click through to the registration page. But even Mark’s involvement was inadequate to bridge the credibility gap for some.

European Beer Bloggers Conference 2011: Hop pickers on stilts escort delegates from the old Whitbread brewery in Chiswell Street, City of London, to Dirty Dick's pub, courtesy of Wells & Young's. In the event 72 people took a chance, assembling on Friday 21 May at the wonderfully appropriate main venue, the old Whitbread brewery on Chiswell Street on the northern edge of the City of London. Most of those were bloggers, with some mainly print writers, covering the spectrum from unpaid ‘citizen bloggers’ to successful professional writers who also blog, and a handful of industry people. Most were from the UK, unsurprisingly given the number of beer blogs based here and the language issue, but with a smattering from Belgium, France, the Irish Republic, Italy, the Netherlands and Sweden. A number confided later they had no idea what to expect. Collectively, however, we were not disappointed, for #EBBC11, as it was rapidly hashtagged on Twitter, turned out to be a remarkable and highly rewarding weekend — surely one of the most exciting beer-related events ever staged in Britain. It also had the feeling of being the beginning of something which can only get even better and more significant.

Allan Wright of Zephyr Adventures making one of his exemplary briefings to delegates. Interestingly, it took a US-based event organiser to convince us of our own significance. Allan Wright runs Zephyr Adventures, a small adventure holiday company based in Red Lodge, Montana. Through organising wine tours, Allan had encountered the wine blogging scene and for several years has run wine bloggers’ conferences in both North America and Europe. Thinking from a US perspective, a beer bloggers’ conference seemed a logical step and the first one was held in Boulder, Colorado, last year. I must admit that at this point I’d have been shaking my head at the obvious next challenge and thinking “it might work here but is it really going to work in Europe?” But in true American style Allan saw the opportunity and went for it. A little desk research led him to Mark and everything started to take shape.

In the process, Zephyr has stolen a march on the indigenous organisations. Committee members of the British Guild of Beer Writers could be heard at the conference muttering things like, “Why didn’t we do something like this?” CAMRA seems to have either failed to notice or chosen to ignore the event — perhaps unsurprisingly given its national chairman Colin Valentine’s recent rather boggling tirade against the ‘bloggerati’.

Most importantly, the brewers took it seriously, even some of the multinational ones. Molson Coors was a major presence, hosting a superb dinner on the first night. In attendance at this were two giants of brewing that both now operate under the Molson Coors umbrella — Sharp’s Stuart Howe and the legendary Steve Wellington, custodian of White Shield, who used the occasion to announce his impending retirement. Other significant supporters included Brain’s, Fuller’s, Hall & Woodhouse, Marston’s and Wells & Young’s. The effusive Václav Berka, head brewer at one of the world’s best known breweries, Plzeňský Prazdroj (Pilsner Urquell), flew in from Bohemia with a supply of unfiltered pils for a party in a room decked out with cardboard cutouts of the Plzeň townscape, as seen in the brewery’s impressive new stop frame animation commercial.

Beer and food matching, courtesy of the Beer Academy. Free beer flowed copiously, and some of the attendees were clearly overwhelmed by the attention. Irish-based Reuben commented on his Tale of the Ale blog that he was treated like royalty. “We were treated like the gods of the blogosphere,” wrote Hayo on Dutch blog Beste tot nu toe.

Not that it was just one big boozeup — in fact most of the event was taken up with much more sober conference sessions, which by and large were extremely useful, interesting and engaging, with lots of open and lively discussion. Among those that most impressed were Peter Haydon’s erudite history of the big London porter brewers; Pete Brown and Tim Hampson in a sparkling, near-unscripted conversation on the past and future of beer writing; Pete again, alongside Melissa Cole and Mark Fletcher, dispensing blogging wisdom such as being aware of your audience, brevity and the ethics of freebies, highly appropriate under the circumstances; and workshops on technical beer tasting from FlavorActiV and beer and food matching from the Beer Academy.

The FlavorActiV workshop, in which we were invited to smell and taste six samples of Carling (courtesy of Molson Coors) that had been deliberately “spiked” with off flavours, was instructive if sometimes confusingly presented. I was relieved I recognised nearly all of the problematic flavours I’ve been writing about for years, but the oddly elusive, harsh and acidic note that results from a “lightstruck” beer in a clear glass bottle provoked the most discussion. It also yielded one of the event’s jaw dropping moments when a brewer from Shepherd Neame defended his brewery’s use of clear glass by asserting that being “sunkissed” was now regarded as a flavour characteristic of Whitstable Bay Organic Ale. Presumably they give each bottle a last turn on the sunbed before dispatching it.

Serving up Windsor & Eton Conqueror Black IPA at the Live Beer Blogging session. Funding and resourcing a big event like this inevitably favours the presence of big names, which could give it a rather glossy, corporate flavour — but in brewing that’s thankfully offset by the genuine enthusiasm and love that pervades every level of the profession. And balancing things out were two events where smaller brewers shone. The Live Beer Blogging session on the Saturday afternoon included beers from the likes of Wallonia’s Brunehaut, Italian speaking Switzerland’s Bad Attitude and southeast England’s Windsor & Eton. The day ended at Camden Town brewery for a Night of Many Beers that included a range of Italian and Swedish craft beers making rare British appearances.

Indeed the theme of the relationship between big beer and small beer threaded through some of the meatier discussions at the event. Molson Coors’ director of public affairs Scott Wilson struck what I thought was a slightly defensive tone in his opening welcome speech with a plea to celebrate all beer rather than harping on divisions between craft and non-craft beer. Later David Sheen from trade body the British Beer & Pubs Association showed us some market research that suggested the majority of people don’t understand beer has a huge diversity of flavours and can partner a wide variety of foods.

When I suggested this may be because the weight of marketing over several decades has been to position a few unchallenging and innocuous beers as everyday bulk refreshers, distinguished from each other more by their funny adverts than their flavours, Scott snapped back that already dividing lines were being drawn, and that Carling is a speciality beer among the very large number of people for whom it is special. Next day the same company’s Kristy McCready — herself a great beer enthusiast and prolific tweeter — challenged BrewDog’s Martin Dickie, complaining he and his colleagues had attempted to boost their position by attacking other brewers’ beers as bland.

Real Ale Girl Shea Luke (left) and Pencil & Spoon's Mark Dredge in live beer blogging mode. Now, of all the multinational brewers, I have considerable time for Molson Coors, at least as regards their interventions in the UK. They do actually seem to get craft beer, offering a number of products that for some drinkers will act as a stepping stone from mainstream beers to more challenging but ultimately more satisfying products. They have also provided an environment in which brewing talents like Steve Wellington can flourish, and I’m confident they will do the same for Stuart Howe at Sharp’s, continuing to support the production of small batch wonders like the partly distilled 24% Turbo Yeast Unspeakable Abhorrence from Beyond the Ninth Level of Hades III which we enjoyed after dinner on Friday night, as they’ve enabled Steve to pursue loving historical recreations like P2 and Bass No 1 at the Coors Visitor Centre.

This way to more free beer. But the idea that we shouldn’t make distinctions between mainstream beers and more specialist examples, let alone rank them in order of merit, doesn’t bear much examination. It also seems to fly in the face of marketing sense. Specialist beers are special precisely because they’re not mainstream, and have a more limited appeal to a more knowledgeable consumer — one that either always looks for a different experience from a beer than they’ll find in the mainstream, or who drinks mainstream beer in certain circumstances but finds specialist beer more appropriate for others. BrewDog have arguably crossed the line in some of their provocations, and Martin, clearly an instinctive rebel rather than a theorist, stumbled when challenged by Kristy. But they’re only following in the footsteps of US brewers like Stone in positioning their beers as products that aren’t for everyone, flattering their customers for setting themselves apart from the “bland” mainstream in choosing BrewDog beers. And it makes sound marketing sense.

And in the end, as an old-fashioned sceptic of the postmodernist thesis that everything is relative, I do think there are grounds to say that beers like Punk IPA and Thornbridge Jaipur and Rochefort 10 and Stone Smoked Porter, and indeed Worthington White Shield and Turbo Yeast Unspeakable Abhorrence from Beyond the Ninth Level of Hades III, are better and more valuable, in the grand scale of human culture, than Carling and Fosters. There’s nothing wrong with brewing or drinking the latter, but if beer is your chosen field of human endeavour, then the pursuit of creativity and excellence, and the appreciation of both, surely leads you to the boundaries of possibility rather than languishing in the comfort of the mainstream. And difficult though it might be to articulate, particularly in a culture like Britain’s which traditionally ducks explicit value judgements in favour of supposedly uncontroversial empiricism, I suspect most of the people at the conference instinctively feel this too.

Pete Brown inadvertantly touched on this point when he talked about knowing the audience and our motivations for writing and blogging. “How many people here blog because they want to persuade more people to drink more interesting beers?” he asked. And the majority of people in the room put their hands up. There’s nothing to be ashamed of in the pursuit of excellence.

Beer picks

- Belhaven Innis & Gunn Canada Day 2011 8.2% Dunbar, East Lothian, Scotland

- Molson Coors UK William Worthington Red Shield 4.2% Burton upon Trent, Staffordshire, England

- Nynäshamns Bedarö Bitter 4.5% Nynäshamn, Södermanland, Sweden

- Plzeňský Prazdroj kvasnicový 4.4% Plzeň, Plzeňský kraj, Czech Republic

- Sharp’s Turbo Yeast Unspeakable Abhorrence from Beyond the Ninth Level of Hades III 24% Rock, Cornwall, England

- Ticinese Bad Attitude Two Penny Porter 8.15% Stabio, Ticino, Switzerland

Banner for the Toer de Geuze 2011 on display at 3 Fonteinen. Snobbery aside, there are some potentially defensible grounds on which to build a case that making wine is a higher field of human endeavour than making beer. Winemakers squeeze the maximum complexity and variety from the minimum of means. From New World varietal superplonk to grand cru classé, it’s all just grapes and a huge amount of human skill, patience and experience. And quite likely those grapes were grown only a few hundred metres from where they were crushed, fermented, matured and bottled, giving the resulting wine a unique provenance, an unbroken, traceable link between the soil and climate of the vineyard and the liquid that finally glugs from the bottle. Winemakers might justifiably claim that brewers, with their huge choice of dry ingredients and their lab-reared libraries of yeast cultures, have it easy. Where is the struggle with nature, the umbilical link with the land?

But then there’s lambic.

Gigantic wooden tuns at Boon, Lembeek. This family of commercially produced spontaneously fermented beers, still surviving and indeed now even modestly expanding in a few pockets of Belgium, perpetuates the specific engagement with the immediate environment that was once the everyday experience of all brewers. The method still might not have quite the simplicity of winemaking, and still draws on a mix of dry materials, these days sometimes trucked long distances. But the fermentation process at its heart is as primeval as brewing gets, rejecting the legacy of Louis Pasteur and instead throwing the wort open to the elements, inviting a whole menagerie of airborne wild yeasts to infect and ferment it. The local microclimate, most notably in the style’s heartland of the Pajottenland, in the valley of the river Zenne west and southwest of Brussels, stamps its imprint on the beer through the microorganisms it nurtures. So do the casks in which the beer is matured and even the very bricks of the breweries.

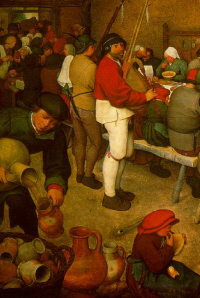

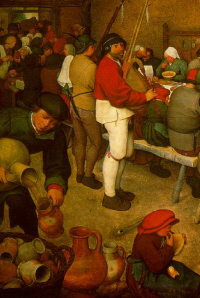

Pieter Bruegel de Oude, De Boerenbruiloft, detail: note lambic at left. Lambic brewers like to point to the famous bucolic painting De Boerenbruiloft (Peasant Wedding) by Pieter Bruegel de Oude (1525-69), which includes a depiction of someone dispensing straw coloured beer from a large ceramic crock. There’s a reproduction of the painting on display at lambic blenders De Cam in Gooik, next to a microscopic enlargement of assorted wild yeast cells. Appeals to centuries old tradition are of course a familiar trope in beer marketing, though rarely can the products concerned trace their history much further than the 1950s, or the 1720s at a push. But in the case of lambic, the appeal to history is almost certainly justified. Why it survived is a puzzle, but survive it clearly did, in defiance of all the trends of the industry over the past century and a half, even more of a delightfully stubborn anachronism than British cask ale.

If lambic is one of the world’s most important beer styles, then the flagship celebration of lambic brewing, the Toer de Geuze, must be one of the world’s most important beer events. Shame on me, then for being so tardy in parcipating, but the event’s infrequent timing, on the first Sunday in May of odd numbered years, has caught me out until now. It’s organised by HORAL, or Hoge Raad voor Ambachtelijke Lambiekbieren, which translates rather pompously into English as ‘high council for craft-brewed Lambic beers’ but is simply the trade association for lambic brewers and blenders in the Pajottenland and Zenne valley. They work closely with the volunteers of De Lambikstoempers, the local affiliate of Belgium’s beer consumer organisation Zythos.

The Toer, which has just been mounted for the eighth time, is essentially a doors open day for the lambic industry. HORAL members throw open their doors for brewery tours, tastings and beer sales, with catering, live music, bouncy castles and other activities completing the offer of a fun day out for all the family. HORAL organises tour buses which this year plied eight routes, each taking in five of the nine participating sites. Or you can find your own way round, with cycling a particularly popular mode of travel. Other organisations also lay on transport — commercial operator Podge’s Belgian Beer Tours and Dutch beer consumer organisation PINT were among those out and about this year. The bars and tastings are an excellent opportunity to try the various HORAL members’ straight lambics, most of which usually end up in blends.

With little idea of what each brewery might offer the visitor, I spent €12.99 prebooking HORAL’s bus route 1, which was covering a couple of my favourites and a couple I was curious about. So I found myself at 1015 on a beautifully bright and sunny Sunday at Halle station, boarding a comfortable double decker coach. Welcoming me aboard was the very knowledgeable and amply hirsute Johan ‘Wanne’ Madalijns, chair of the Lambikstoempers. My fellow passengers were mainly Flemish and mainly male, though with a good range of ages, and a smattering of Brits, Dutch, Italians, North Americans and Scandinavians. The news on VRT-1, the main Dutch language TV channel, reported with some amazement that evening on visiting Americans, including Pete Slosberg of Pete’s Wicked Ale fame. But it was reassuring to see so much national support for a beer style which only a couple of decades ago was on the brink of extinction.

Indeed this was a very Flemish occasion and I was glad of my Dutch skills. Lambicland largely falls within Vlaams-Brabant, in the Dutch speaking part of Belgium, which wraps to the south of the officially bilingual but predominantly francophone Brussels Capital Region as a narrow strip separating it from French-speaking Brabant-Wallonie. All the lambic enterprises are in Flemish territory except Cantillon in Brussels, not a HORAL member, and the soon-to-launch Tilquin, of which more in a later post. As we approach, Wanne introduces each brewery in Dutch, asking people to translate if necessary for their neighbours. Most of the brewery tours are also conducted in Dutch, though the guides happily deal with individual enquiries in English.

This is one of Europe’s most populated areas, and no more than ten minutes on the train from the busy international rail interchange of Bruxelles-Midi, but the surroundings are surprisingly rural, and attractively lush and green in the sunshine. Rolling lanes run between small woods and fields where Belgian Blue cattle graze, and our coach is clearly uncomfortable in the narrow streets of the villages that liberally dot the landscape.

Karel Goddeau of De Cam, Gooik, with lambic cask. First stop is De Cam, attached to a community centre, musical instrument museum and bar in the village of Gooik, the self-proclaimed ‘pearl of the Pajottenland’. The building dates from 1515 and was a brewery in a former incarnation — the name is an old dialect word for brewery. The current beer-related activity is more recent, dating from 1997 when Karel Goddeau set up shop as a lambic blender, buying in lambics from Boon, Girardin and Lindemans and brewing himself at 3 Fonteinen. Karel welcomes us and explains how the unusual process of lambic production facilitates such collaborations.

Wild yeasts typically ferment slowly, and the resulting product is too acidic to drink when young, so the beer is matured in wooden barrels, both to complete its fermentation and to round off the rough edges. Age is usually quoted in years but strictly speaking it is measured in summers, reflecting the seasonal cycle of lambic brewing, which is only practical in cooler weather. Beer is aged for one or two summers, occasionally for three or four. Given the unpredictability of the wild yeast, consistency is achieved through blending, and palatability is also enhanced, famously, by steeping fresh fruit in the beer.

There’s no reason why maturation, steeping and blending can’t take place in a different location from the one where the beer was brewed, creating openings for specialist blenders, known in Dutch as geuzestekerijen. Day old beer, already colonised by the local yeasts, is transported in bulk from the brewery to the stekerij, where it’s placed in large oak barrels or tonnen. These are normally venerable old vessels that have been reused many times – most of those at De Cam are 1,000l capacity vats that were originally used for lagering at Plzeňský Prazdroj (Pilsner Urquell).

De Cam proudly displays a local CAMRA Beer of the Festival award. “Lambic,” says Karel, “is the mother of all beers,” recounting that it can be traced back in the Pajottenland at least to the year 1400, while the sparkling blend of lambics known as geuze (gueuze in French) was perfected from the 1820s. “Lambic is basically a flat beer, “ he tells us, “so for geuze we ferment year-old lambic with three- or four-year-old beer. The younger beer wakes up the fermentation and the older one cools it down a bit. It all depends on temperature, acidity and nine different microorganisms, including brettanomyces.

“Everything in the bottle is wholesome and healthy,” he continues, “and there are less calories in a bottle of our geuze than in a glass of milk. It’s full of antioxidants, which also protect it – geuze will keep for 20 years after the bottling date. If you have a cellar with a constant temperature of 10-12°C, lay down a couple of bottles of geuze every year, and within twenty years you’ll have heaven on earth in your cellar.”

Karel’s geuze, like nearly all the best examples, meets the protected European definition of oude geuze (oude meaning ‘old’), containing 100% spontaneously fermented beer with no additional sugar, unpasteurised and fermenting in the bottle. The cherry-steeped kriek is similarly designated oude, with 900kg of sour cherries added to 1500l of lambic. The traditional Belgian fruit variety used, Schaarbeekse krieken, named after Schaarbeek, a former village just to the north of Brussels city centre, are sometimes not available in large enough quantities so morellos from Limburg are substituted, or if necessary frozen sour cherries from Poland.

De Cam is a relatively small operation, essentially a barn with a blending vessel and all those Bohemian vats quietly doing the business. The tour ends with a free tasting from the bar in the adjoining café, where an impromptu band performs a folksy jam on guitar, accordion and bagpipes, the last another echo of Bruegel’s wedding scene.

Seeing the light at De Troch, Wambeek. Next up is De Troch, one of the most fascinating stops on the tour. It’s best known for its extensive range of sweetened low gravity concoctions of lambic and exotic fruit juices under the Chapeau brand, which hasn’t endeared it to fine beer enthusiasts, but it has one of the longest pedigrees of all the surviving lambic breweries. Dating back to the early 18th century and clustered round a courtyard next to an associated drinks warehouse in the centre of the village of Wambeek, its buildings certainly look the part of the village family brewery. The small first floor brewhouse was spring cleaned in 2004 following a health scare but is still creaky and cobwebbed, with light shining through gaps in the tiled roof above. “Think how much water is in your beer, madam” quips our guide to a visitor who points this out.

A remarkably small mash tun (roerkuip in Dutch) from the 1930s, the oldest of its type still in use, is employed to mash barley malt, mainly pale but with a smattering of darker malt, and unmalted wheat – a 1986 law specifies at least 30% wheat must be used in lambic. The mashing temperature is raised in five steps between 45° and 78°C to achieve optimal release of enzymes. Next the wort is boiled in copper kettles with considerable quantities of aged hops, mainly from the Czech Republic with some from Germany, which retain their preservative and stabilising qualities but without the bitterness and aroma that would clash with the sourness of the finished beer. The brew is then filtered and run to the immediately adjacent steel lined koelschip, the characteristic broad, shallow vessel resembling a paddling pool in which the fresh wort is left to consummate its union with the local microflora. This requires it cooling to a temperature less than 18°C, or ideally under 15°C, therefore the limitation on summer brewing.

De Troch lambic and some of its less connoisseur-friendly derivatives. Before it earns the designation lambic, the wort has to spend a few months in wooden vats, of which De Troch has an extensive magazine, each one lending its contents an individual character. At six months it might be used for fruit beers or as part of the geuze blend, but De Troch ages lambics for up to three years, including for use in its oude geuze, Chapeau Cuvée. “Once people were happy to drink sour lambics,” says the guide, “but then they wanted sweeter and sweeter beers. Now it’s changing with demand going back towards sour beers again.” Good to hear in a lovely old brewery which still doesn’t quite live up to its potential.

Crowds converge on Boon, Lembeek. Then we’re off to the village that gave its name to the style, Lembeek, and to Boon, the biggest and best known establishment on my trip. Frank Boon first blended lambic in 1975 when he bought the old De Vits brewery at Halle, moving into brewing in 1990 and shortly afterwards expanding into this former metalwork factory, literally on the banks of the infant Zenne. It operates in partnership with national brewer Palm, but Frank has retained credibility while pursuing commercial success, notably in the export market, and is recognised as one of the saviours of lambic.

It’s lunchtime and Boon’s extensive site is thronged with people enjoying beer, sausages and roast meat (nothing for veggies – I end up resorting to a packet of crisps and a plate of cheese at one of the village pubs), music and brewery tours conducted with impressive efficiency by a small army of brand-compliant guides. Inside the brewhouse, a red-painted mash tun is in action, its rotating blades lazily stirring a steaming porridge of barley and wheat. Given the warm weather I guess this may have been laid on for the visitors.

Mash tun in action at Boon, Lembeek Boon boasts a generously proportioned koelschip, alongside some extensive blending vessels and a fine collection of oak tuns, some of which are gigantic, with a capacity of over 7,000l, big enough to hold a small drinking party in. No simple bungs here – the biggest tuns are accessed using chunky metal devices that might challenge the skills of a professional safe picker. The three-year-old lambic we’re offered straight from one of these is absolutely divine, one of the most extraordinary beers I’ve ever tasted.

Our final calls are both in Beersel, another important lambic village, though its name looks curiously appropriate only to English eyes. Sadly the Toer is a fortnight too early for its new Lambic Visitor Centre, due to open on 15 May. The village, atop a steep hill climbed by a winding lane that seriously challenges our coach, is also famous for its distinctive castle, once the seat of the Seneschal of Brabant.

I’m looking forward to 3 Fonteinen, territory of another legendary saviour of lambic, Armand Debelder. His family owned a pub in the village since 1953, one of the few to perpetuate the once common tradition of maturing and blending its own geuze, and Armand developed these blends into a well respected brand. In the 1990s, fearing that the rapid decline in the industry threatened future supplies, the company began to brew its own lambic, but in 2009 a faulty thermostat destroyed much of the (uninsured) stock of maturing bottled lambics and the financial impact of this has seen them scaling back to a simple geuzestekerij again for the foreseeable future.

Boterham Jeroen Meus and a 3 Fonteinen Oude Geuze at the Lambikodroom, Beersel. In the event I’m disappointed as there’s not much to see, with no tours of the old brewery or maturation rooms. The narrow yard is uncomfortably packed with visitors, with several coach parties arriving at once. Somewhere in the throng is celebrity chef Jeroen Meus signing copies of his latest book Dagelijkse Kost (‘Everday food’). For the occasion he’s devised an interpretation of the traditional lambic beer snack, plattekaas, a mild, white and foamy local cream cheese spread on a big slice of farmhouse bread. Normally this comes with spring onions and radishes, but the boterham Jeroen Meus is flavoured with horseradish and honey, spinkled with walnuts and garnished with fresh watercress from nearby Loonbeek. I squeeze into the slightly quieter surrounds of the adjoining tasting room, the Lambikodroom, to try one with a geuze – the combination works well but I miss the crunchy radishes.

Entrace to the Geuzestekerij Oud Beersel, the former Vandervelden brewery, Beersel. On the other side of the village is Oud Beersel, formerly the Vandervelden lambic brewery, established in the 1880s – Oud Beersel became its principal brand. Closed in 2003, it was reopened shortly afterwards as a blender and brewing museum by Gert Christiaens, and its current form is partly the result of winning a makeover programme on TV. It’s an atmospheric old place, with two old cylindrical brewing vessels and a koelschip under the authentically cobwebbed eaves, and displays of old brewers’ and coopers’ tools, but they’re for display purposes only. Gert has attracted some criticism for labelling the place a brouwerij when all the beer is brewed and seeded, using Vandervelden recipes, at Boon.

The maturation rooms are still very much in business: the fresh beer is tanked from Lembeek to develop in 500l oak tuns, some of which were previously used for port and are up to 50 years old. Guide Christiaan Robeyns explains how a wide choice of lambics is needed to ensure a consistent blend, as inevitably with spontaneous fermentation, each brew will be slightly different. He also shows us the historic installation that cleans the tuns with a combination of high pressure water, sulphur dioxide and metal chains to scour the inner surface.

Microbiology working its silent magic in wooden tuns at Oud Beersel, Beersel. I enjoy a final lambic across the road, where a temporary collection of bars, food stalls, tables and chairs and yet another bouncy castle is doing brisk business. Then we’re back in Halle and Wanne is wishing us all goodbye and see you in two years. VRT-1 reports that this year’s Toer de Geuze was more successful than ever, with more than 8,000 people in attendance and the HORAL buses selling out weeks in advance. The success is well deserved as this crash course in the wonders of Lambicland must be one of the world’s most unique beer events, giving you a genuine sense of how geography, history and culture are fused in the creation of one of our most extraordinary and precious beer styles.

Beer picks

More information

Toer de Geuze 2011, Top Tastings 2011

ABV: 6%

Origin: Lembeek, Vlaams-Brabant, Vlaanderen

Website: www.boon.be

Traditional lambic crocks and samples at Boon, Lembeek On very rare occasions I taste a beer that’s so extraordinary it sends my rating system off the scale, and this, sampled direct from one of the gigantic oak casks at the Boon brewery during the Toer De Geuze, was one of them. Thanks to his deal with Palm, Frank Boon’s guezes and fruit lambics are now produced on a relatively significant scale and are the most often seen of the authentic “oude” style, which makes them a little too commonplace for the snobbier beer geeks, but for some time now they’ve been consistently good. Their quality reflects that of the base beers maturing in massive casks at the Lembeek brewery, and some of these, if my tasting experiences are anything to go by, are on another plane altogether.

The previous day I’d tasted an old Boon beer matured at another blender which had already rocketed into my top tastings of the year, but this one seriously realigned my scale of beer appreciation. So singular, so breathtakingly complex and sophisticated and yet so beautifully integrated, it was one of the most sublime taste experiences of my life.

As often with old lambics, it had matured into a foxy red-amber colour and was completely flat, with a perfumed, slightly spirity aroma of sherry, dried fruit and nuts. The palate was slightly syrupy, sourish and very, very complex, with mellow vanilla, dried fruit, coconut, vinous fruit, tannins and petrol. A souring but still kind, satisfying and long lingering finish had oily orange peel that developed fuller, fruitier tones, reminiscent of apricot pastry with a scattering of nuts.

And yet clearly not for everyone – some of my fellow brewery tourists were looking uncertain and leaving half-finished glasses. Lambic is indeed an acquired taste, but after sampling this, I had no doubt I’d finally got it.

Read more about this beer at ratebeer.com: http://www.ratebeer.com/beer/boon-oude-lambik/23579/

Toer de Geuze 2011

ABV: 5%

Origin: Gooik, Vlaams-Brabant, Vlaanderen

Website: www.decam.be

De Cam brewery and museum, Gooik De Cam is a blender rather than a brewery, buying in lambics from Boom, Girardin and Lindemans, so I’ve no idea where this beer was actually brewed, but it was matured for at least one summer in one of the Plzeňský Prazdroj casks in Gooik and tasted as a free drink on a visit there during the 2011 Toer de Geuze.

This was an excellent lambic, a slightly hazy pale amber colour, almost completely still with hardly any head. A lovely nutty and apply aroma, only slightly acidic, heralded a dry but fruity and complex palate, with that smacky wet plastic ‘funky’ note, developing quite intense sour apple flavours. The finish was tart but notably matured, with a lingering lemon note and some firm cereal malt coming through.

Read more about this beer at ratebeer.com: http://www.ratebeer.com/beer/de-cam-oude-lambiek/31842/

Toer de Geuze 2011

ABV: 5.7%

Origin: Lembeek/Beersel, Vlaams-Brabant, Vlaanderen

Website: www.oudbeersel.com

Appropriately decorated window at Oud Beersel, Beersel Brewed at Boon in Lembeek to former Vandervelden brewery recipes, the Oud Beersel lambics are tanked to Beersel to undergo maturation and blending. I assume this one, served from a bag in a box at Oud Beersel’s outdoor bar during the Toer de Geuze, was only a year old but couldn’t get confirmation from the bar staff..

Though well worth drinking and as strange and unique as all genuine lambics are, this beer was some notches down in complexity and interest from the truly extraordinary things that can be achieved in the Zenne valley with wild yeasts and cask ageing. It was a flat amber beer with a trace of whitish head and a sharpish, moderately fruity aroma with a distinct citrus note. The palate had more citrus, grapefruit flavours, and that typical funky smack of brettanomyces yeasts, leading to a slightly warming finish with still more citrus, and a light pippy note of apple or cider with pleasantly lingering nutty flavours.

Read more about this beer at ratebeer.com: http://www.ratebeer.com/beer/oud-beersel-oude-lambik/23561/

Toer de Geuze 2011

ABV: 5.7%

Origin: Wambeek, Vlaams-Brabant, Vlaanderen

Website: www.detroch.be

Lambic straight from the cask at De Troch, Wambeek Much of De Troch’s lambic ends up in its sweetened fruit beers which, if this rather fine example is anything to go on, is a great shame. Part of the pleasure of sampling it on the 2011 Toer de Geuze was watching a brewery worker expertly catch the stuff in a jug as it gushed in golden gouts from a big oak vat. A chalk mark on this gave the brewing date as 22 January 2009.

The beer was pale golden and lightly bubbly, with a nutty dried fruit note on the mellow aroma. The wild and fruity citric palate had definite notes of pineapple and other tangy fruits alongside vanilla. A tangy finish spread across the tongue with tart orange flavours, lingering long with fleeting notes of nuts and apricot. It was my first lambic of the day, and a very good start.

Read more about this beer at ratebeer.com: http://www.ratebeer.com/beer/de-troch-oude-lambik/24075/

First published in Beers of the World October 2008

De Bierkoning bierwinkel, Amsterdam Amsterdam has always had a good line in pubs with its celebrated bruine cafés oozing traditional gezelligheid (cosiness, homeliness). But a couple of decades ago you’d have been lucky to find anything other than a foaming but bland Dutch pils with which to soak up the atmosphere. Nowadays the range of beers is massively improved, and, as befits the capital of a trading nation, they are sourced from all over. In fact Belgian specialities can be easier to find than the products of the emerging crop of Dutch micros.

Binnen de Bierkoning: een grote assortiment Nederlandse bieren City centre beer shop De Bierkoning – the Beer King – has been widening the tastes of Amsterdammers since 1985. Former market trader and sound engineer Jos van Niele opened it out of frustration with the difficulty of buying speciality beer locally. Jos is still in charge, and now employs a staff of three. Though no longer the only specialist beer shop in the city, it’s the biggest and best-established and, with its impressive and well-chosen range and enthusiastic and expert customer service, it’s arguably one of the best in Europe.

Around 900 different beers are cleverly shoehorned into a modestly-sized space, while leaving room to browse in a pleasant natural wood interior while filling up your attractive woven basket. Almost half are Belgian, with several rarities and aged beers, and a small downstairs area devoted to quality lambics. Brits and Germans get a good showing, and there are some well-chosen bottles from the USA, Czech Republic, Russia and elsewhere. But perhaps most impressive is the large range of Dutch specialities, from veterans like Brand and Gulpener alongside relative newcomers such as local brewer ’t IJ, which brews a special beer, Vlo, for the shop, and current international cult success De Molen.

Een glas voor een koning gepast “We focus on specialities, not supermarket beers,” says Jos, “preferably from smaller brewers. The quality of Dutch microbrewers is improving – we’re particularly enthusiastic about the beers from De Molen right now. And we’ve commissioned another new beer ourselves, Labelle’s Chocoladestout (chocolate stout) from De Schans in Uithoorn, which I just tasted and found sublime.” There are shelves for seasonal beers – visit in the autumn and you’ll find a comprehensive range of Dutch and other boks – and preselected mixed cases. Then there’s around 300 different glasses, plus books, T-shirts and breweriana. Organised tastings can also be arranged.

De Bierkoning, Amsterdam Like the beers, the customers come from far and wide including the US and Britain – as usual for cosmopolitan Amsterdam, English is fluently spoken. The shop enjoys a prime site a few paces from Damplein and, fittingly for a beer king, around the corner from the Royal Palace. As beer sellers go, this is one of the crown jewels.

Fact file

Address: Paleisstraat 125, 1012 RK Amsterdam

Phone: +31 (0)20 625 2336

Web: www.bierkoning.nl

Hours: Mon 1300-1900, Tues-Fri 1100-1900, Sat 1100-1800, Sun 1300-1800

Drink in? No

Mail order: Currently selected mixed cases and glasses only, though upgrade is planned. Email for delivery charges if outside Netherlands.

Manager’s favourites: “Hoppy beers, from blond to black”

Beer picks

- ’t IJ Speciale Vlo 7%, Amsterdam, North Holland. No half measures for this house beer, a big, vivid golden ale with sweetish body, bready yeast, bitter hop and powerful coriander notes.

- De Molen 1914 Porter 5.8%, Bodegraven, South Holland. Limited production authentic chocolate biscuit and roast porter from restlessly inventive rising international star.

- St Christoffel Blond 5%, Roermond, Limburg. One of the world’s best pale lagers, unfiltered, unpasteurised, long, dry and packed with peachy malt and intoxicating hops.

- Schans Van Vollenhoven’s Extra Stout 7%, Uithoorn, North Holland. Blackcurrant, smoky bacon, malt loaf, nuts, caramel and charred wood mix in a complex and welcome revival of a speciality abandoned by Heineken.

- Schelde Schoenlappertje 6.5%, Bergen op Zoom, North Brabant. “The only genuine Dutch fruit beer”: real blackcurrants from South Beveland add red tinge and a minty Cabernet Sauvignon tartness to a juicy, malty amber ale.

|

Cask  This pioneering new book explains what makes cask beer so special, and explores its past, present and future. Order now from CAMRA Books. Read more here. This pioneering new book explains what makes cask beer so special, and explores its past, present and future. Order now from CAMRA Books. Read more here.

London’s Best Beer  The fully updated 3rd edition of my essential award-winning guide to London’s vibrant beer scene is available now from CAMRA Books. Read more here. The fully updated 3rd edition of my essential award-winning guide to London’s vibrant beer scene is available now from CAMRA Books. Read more here.

|