They say…

Best beer and travel writing award 2015, 2011 -- British Guild of Beer Writers Awards

Accredited Beer Sommelier

Writer of "Probably the best book about beer in London" - Londonist

"A necessity if you're a beer geek travelling to London town" - Beer Advocate

"A joy to read" - Roger Protz

"Very authoritative" - Tim Webb.

"One of the top beer writers in the UK" - Mark Dredge.

"A beer guru" - Popbitch.

|

London’s Best Beer, Pubs and Bars updates

Central London: Borough

Contemporary pub (Independent, small group)

231 Long Lane SE1 4PR

T 020 7357 8740 w www.simonthetanner.co.uk f simonthetannerlondon tw Simon_theTanner

Open 1200-2300 (2230 Sun). Children welcome until 1900.

Cask beer 3 (Adnams, 2 unusual often local guests), Other beer 6 keg (UK & international), 15 bottles, Also Real cider, 10 wines.

Food Imaginative gastro/pub grub, Wifi. Disabled toilet.

Tue quiz, Wed live piano.

Simon the Tanner, London SE1. Pic: Simon the Tanner This corner of Bermondsey is a typically curious London mix: arty gentrification along Bermondsey Street which has been hailed by Vogue as the coolest street in south London; an old established antiques market formerly notorious for trading stolen goods now housed in a regenerated square overlooked by a boutique hotel; and remaining patches of 1930s and 1960s social housing once populated by dockers or workers in local industries such as the leather trade. That now vanished occupation is recalled in the unusual name of this recently made-over pub which now provides the area with a much needed outlet for great beer.

A pub for over 200 years, Simon the Tanner lay derelict for six years before being reopened in 2011 by the same group that runs the lovely Queens Head near Kings Cross. Like that pub, it’s a friendly community venue with a great beer choice – a little less varied than its sister pub but still much better than average. There’s a changing Adnams cask beer, plus two others that might come from the likes of Buntingford, Castle Rock, Cottage, Mighty Oak, Redemption, Tring or Windsor & Eton. Interesting keg beers include organic Black Isle Porter from Scotland, BrewDog 77 Lager, Duvel Green and a changing guest US beer, while among the bottles are examples from London brewers London Fields and Redchurch as well as several Brooklyn beers and Schlenkerla smoked beer.

A shortish food menu has reasonably priced pies, charcuterie boards, vegetable risotto, ploughmans with speciality cheese and tempting home made desserts like apple, pear and walnut crumble. It’s a smallish place, tastefully decorated in greys and pale greens with Andy Warhol prints, a mixed crowd and an especially relaxed and welcoming atmosphere that makes it something of a hidden gem.

National Rail River London Bridge Underground Borough Cycling LCN 22, link to NCN 4, LCN+ 183 Walking Link to Jubilee Greenway, Jubilee Walkway, Thames Path

London’s Best Beer, Pubs and Bars updates

Central London: Borough

Restaurant (bar) (Wright Brothers)

11 Stoney Street SE1 9AB

T 020 7403 9554 w thewrightbrothers.co.uk f WrightBrothersOysters

Open 1200 (1100 Sat)-2300 (2100 Sun).

Cask beer None, Other beer 3 keg, 10 bottles (mainly stouts and porters), Also 40+ wines including sparkling and sherry.

Food Oysters, seafood, fish, Outdoor Stools and barrels on street.

Wright Brothers Oyster and Porter House, London SE1 Pleasingly, this Borough Market shopfront for Cornish oyster fishery Wright Brothers honours its beer friendly surroundings by foregrounding porters and stouts as the ideal accompaniment to the company’s principle product. The drinks lists goes considerably beyond the obvious Draught Guinness in offering an impressive choice of the dark stuff, appropriately enough for an outlet a stone’s throw from the site of what was once one of the greatest porter brewers in the world, Barclay Perkins. Suppliers include local brewers Kernel and Redchurch as well as Anchor, Harviestoun, Palmers (the oyster stout commissioned by celebrity chef Mark Hix), Meantime, Pitfield, St Peter’s and Whitstable. Decent lager and Kernel IPA are on sale for the roasted malt-shy, and then there’s the more expensive but equally traditional matching option of champagne.

Five varieties of oysters are served, as well as mussels, shrimps, crab, various fish and beef, Guinness and oyster pie: vegetarians will find themselves rather at sea, and prices nudge into posh restaurant territory. Non-diners might be able to squeeze themselves a stool at the bar at quiet times, but this is a small, intimate place with the limited table space reserved for diners, perhaps taking advantage of the seductive bivalve’s reputed aphrodisiac properties, and pre-booking is advised.

National Rail Underground River London Bridge Cycling Links to NCN4, CS7, LCN+ 22 23 183 Walking Link to Jubilee Greenway, Jubilee Walkway, Thames Path

Traditional pub (Interpub/Beds & Bars)

121 Borough High Street SE1 1NP

T 020 7407 2392 w www.stchristopherspub.co.uk

Open 1000-0100 (0200 Fri-Sat). Children welcome until 1900.

Cask beer 5 (Rebellion, St Austell, 3 often unusual guests), Other beer 5 keg, 20+ bottles (mainly Belgian).

Food Shortish pub grub menu, Outdoor Benches in side alley, Wifi. Disabled toilet.

Thu-Sat live music, occasional big screen sport (not football), functions.

St Chrisophers Inn, London SE1. Pic: Interpub This old pub on the corner of one of Borough High Street’s historic coaching yards is owned by an international backpackers’ hostel group, which offers accommodation both above the pub and at other addresses in the High Street (central reception is at number 161). It was previously run as a hostel bar, aimed squarely at a youthful, studenty crowd. The company began as a pub operator, though, and a couple of years back returned to its roots by restoring a traditional feel that now attracts a higher proportion of Londoners than young travellers. The long, narrow space is done out in dark wood, with bare floorboards and drinking shelves. There’s extra space towards the back with more loungey seating, and a function room in the cellar.

The international connection is preserved in a wide range of beers, though perhaps not quite as much as the 100 varieties promised by advertising. Rebellion IPA and Tribute are regulars on the handpumps, with guests coming from brewers like Aylesbury, Bath, Purity or Vale. Paulaner Hacker-Pschorr Pils, Meantime London Stout and Huyghe Delirium Tremens are on keg, while the bottled range has a Belgian slant: Chimay, Duvel, Lefèbvre Barbãr and Palm Steenbrugge Tripel are highlights, while some good choices from Meantime and American standards like Anchor Steam increase the choice. A shortish menu of fresh cooked comfort food with ingredients sourced from nearby Borough Market – gammon and chips, Pieminster pies and mash, grazing platters – has moderate prices for the area.

Insider tip. The inscription in Dutch over the bar, presumably inspired by sister venues in Amsterdam, reads “In de hemel is geen bier, daarom drinkt wij het hier” (There’s no beer in heaven, so we drink it here).

National Rail River London Bridge Underground Borough, London Bridge Cycling Links to NCN4, CS7, LCN+ 22 23 183 Walking Link to Jubilee Greenway, Jubilee Walkway, Thames Path

London’s Best Beer, Pubs and Bars updates

Central London: Borough

Traditional pub (Nicholson’s/M&B)

26 Hays Galleria SE1 2HD

T 020 7407 1991 w nicholsonspubs.co.uk

Open 1000-0030 (2330 Mon-Tue, 2400 Wed, 2300 Sun). Children welcome if dining.

Cask beer 10 (Fuller’s, Sharp’s, St Austell, Thornbridge, 6 Nicholson’s guests) Cask Marque, Other beer 3 keg, 3 bottles, Also A few wines.

Food Nicholson’s pub grub menu, Outdoor Terrace on Thames Path, Wifi. Disabled toilet.

The Horniman at Hays, London SE1. Pic: M&B On a prime site on the Thames Path right by HMS Belfast, overlooking a stretch of river that was once thick with shipping, the Horniman is also handy for City Hall and the More London development. It makes the best of its river views with a long frontage and an extensive terrace. Indoors is spacious, with a correspondingly long bar and a mezzanine-style balcony, though it’s often busy.

This is a Nicholson’s pub furnished in their traditional saloon bar style, and though its beer selection is not in the same league as some of the outstanding beer pubs in the area, it’s generous by the standards of this reliable chain, and the environment would suit a family outing. London Pride, Doom Bar, Tribute and (usually) Jaipur are the fixtures, while the remaining six pumps explore the pubco’s seasonal lists: Box Steam, Brains, Brentwood, Wold Top and one of the Project Venus collaboration beers were on when I called. You might also catch Brooklyn Lager or Shepherd Neame beers in bottle, and Hoegaarden on keg. Food is a slightly more expensive version of Nicholson’s standard ‘pub grub plus’ menu though this is one of the more affordable options in a generally upmarket area – look out for the early evening fixed price deal.

Visitor note. A former home of one of Southwark’s once plentiful breweries, this site became a dock and warehouse complex known as Hays Wharf in the 1840s. Shortly afterwards it was taken over by the tea trading Horniman family, and by 1891 it was the centre of the world’s biggest tea business. In the 1980s developers covered over the dock and added a high roof to create Hays Galleria, a spectacular public space surrounded by specialist shops and dominated by David Kemp’s fascinating kinetic sculpture The Navigators. The pub was opened in one of the adjoining warehouses in 1997.

National Rail Underground River London Bridge Cycling NCN 4, LCN+ 22 183 Walking Jubilee Greenway, Jubilee Walkway, Thames Path

Abbaye des Saveurs, Lille A major interchange on the fast rail routes connecting England, Belgium and the Netherlands with France, Lille is the sort of place you remember primarily for passing through. Many a Belgian-bound British beer enthusiast will have found themselves hastily clearing up the formerly empty seat next to them for the benefit of a passenger joining at what the Dutch language announcement terms “Rijsel, station Lille Europe.”

This is a shame, as Lille turns out to be a fascinating city, the regional capital of Nord-Pas de Calais and the archetype of what the French have in mind when they think of ‘le nord‘. Founded by the Dukes of Flanders in the 11th century and seized and fortified in the late 17th century by the French, it’s long stood on the frontier of French and Flemish culture.

Thanks partly to its proximity to important coalfields, in the 19th century it became a major industrial centre, particularly for textiles, and known as the Manchester of France, an apt comparison in several ways. Today it’s at the core of a 1.9million strong conurbation that sprawls over the Belgian border to include Mouscron and Tournai in Hainaut and Kortrijk in Dutch-speaking West Flanders.

Craig Allan and Mont des Cats at Abbaye des Saveurs, Lille Beer lovers have a particular reason to regret not stopping off, as this is also the urban centre of France’s richest regional beer culture. All of historic Flanders and neighbouring Picardy is beer country by geography, climate and tradition. Grains and, formerly, hops flourished here in a climate too cool for grapes and for centuries hundreds of farmhouse brewers slaked the thirst of agricultural workers with rustic ales.

Industrialisation also favoured brewing and the 19th century saw bigger regional breweries emerging to serve the swelling ranks of new proletarians. Growth drove technological development: the great microbiologist Louis Pasteur was based in Lille for much of his life, and worked on his groundbreaking Études sur la bière here.

Iconic northerners -- Ch'ti 'tapis de bar' at Abbaye ds Saveurs, Lille But as in many other places local brewing came under pressure in the postwar period from emerging national brands, mainly emanating from Alsace, another stretch of border country, where the transnational influences are German and lager is the beer style of choice. By the 1970s the wisest local brewers were withdrawing from the losing battle with mainstream lagers and instead reviving the old regional farmhouse style of ‘beer for keeping’, bière de garde.

French gastronomic culture is traditionally sympathetic to regional specialities, and these rejuvenated beers, led by Duyck Jenlain, gained a youthful following among people wanting to express a distinct French-Flemish identity.

From around 2,000 breweries at the beginning of the 20th century, the region boasts a mere 30 today. But these include some of the most vibrant and interesting beer makers in France, as the historic bière de garde producers are joined by an increasing number of new micros, some with ambitions far beyond upholding local tradition.

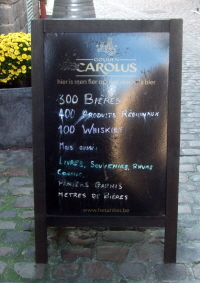

Shop window for local beer: Abbaye des Saveurs, Lille Visit the huge Carrefour supermarket in the striking Euralille development around the international station to find better known regional brands like Jenlain, Ch’ti and Trois Monts at bargain prices. For the smaller brewers, though, you’re best advised to explore Vieux-Lille, the mediaeval core around the island created by the river Deûle that gives the city its name in both languages (‘l’île’, or in Middle Dutch, ‘ter ijssel’). Among the specialist shops in narrow and picturesque rue des Vieux Murs (‘old walls street’, recalling former fortifications), the Abbaye des Saveurs (‘abbey of flavours’) is unique in offering both local and global craft beers alongside specialist regional foods.

The smallish and charming shop is the sort of place a tourist may stumble upon while exploring the alluringly picturesque lanes of the old town, and at weekends in particular it’s well used by visitors from all over France, the UK, Belgium, the Netherlands and further afield loading up with authentic titbits.

Franck di Grégorio proudly displays the house beers at Abbaye des Saveurs, Lille. But the dazzling range and the reasonable prices belie any suggestion of a tourist trap. Its founders – former engineer Franck Di Grégorio and his business partner Anthony D’Orazio, a chemist by training who once brewed at brewpub chain Les 3 Brasseurs – are genuinely and deeply passionate and knowledgeable about their wares.

“If you want to sell beer it’s important you know what it tastes like, the styles and the history,” Franck tells me. “When I began to drink beer at 18 I was first fascinated with sous bocks – beer mats – and wanted to know what the beers they advertised tasted like. So I read lots of books about beer and tasted as many beers as I could. I tried all the traditional Northern French beers then started travelling just to taste beer. I’ve been all over the world, and I have no prejudice about where beers should come from.”

Franck and Anthony noticed that despite the rich regional patrimoine brassicole, Lille’s single specialist beer store sold only Belgian beers. So when they opened the Abbaye in 2005, they were determined it should do justice to the local scene. That emphasis continues today, with the best part of the wall on the right given over to around 90 beers from 23 local breweries.

The impressive regional shelves at Abbaye des Saveurs, Lille Besides a comprehensive range of familiar brands –Ch’ti, Choulette, Goudale, Trois Monts – there are lesser known bières de garde including the delightfully traditional Theillier Bavaisienne, Vieux Lille from Brasserie des Sources and beers from the Annoeullin, Bailleux and Saint-Germain breweries. Then there are the mould-breaking micros, from trailblazer Thiriez to the youthful likes of 2 Caps, Artésienne (Saint-Glinglin), Caou (Kaou’ët) and Pays Flamand.

Among these are the wonderfully distinctive house offerings from Craig Allan, an expatriate Scot and old friend of Anthony from his days as a student in Edinburgh. Though these are currently brewed over the border at Proef in West Flanders, the Abbaye team are working with Craig on opening their own brewhouse in nearby Cassel later in 2012.

Belgian beers have their place too, with a particularly well chosen selection. Lambics might include Cantillon’s dry hopped Cuvée Saint-Gilles, gueuze from new blender Tilquin and serious rarities from 3 Fonteinen (I spotted Armand 4 Saisons at €45). Trappists include the new beer brewed at Chimay for the Mont des Cats monastery, and first class brews from Abbaye des Rocs, Belgoo, Dochter van de Korenaar, Dupont, Ellezelloise, De Ranke, Sint-Bernardus, Saint-Feuillien and Struise are also on sale.

International choices, tellingly, mainly represent talked about new brewers with a global reputation rather than textbook classics. So there’s Thornbridge and BrewDog from the UK, US extreme beers from Stone, Danish gypsy brewer Mikkeller, Molen from the Netherlands, BFM from Switzerland, Dieu de Ciel from Québec and Toccalmatto from Italy. “We do get beer geeks,” concedes Franck, spontaneously using the English term. “Of course our customers travel and use the internet so some of them are familiar with these names.”

Regional delicacies at Abbaye des Saveurs, Lille The food shelves, though, are unashamedly Flemish: pots of carbonnade flamande, several varieties of the mixed meat terrine known as potjesvlees, pâté with beer or genever, various waffles, cinnamon spekuloos biscuits and even spekuloos flavoured spread. Then there’s the local genièvre, beer eau-de-vie from a nearby distillery and a handful of whiskies including imported malts.

“There’s no point in trying to compete with supermarkets,” says Franck. “We can advise people about beer flavours and recommend beers they might like. The supermarkets can’t do that. So a customer might come in wanting one beer and end up buying 10 in different styles.” I imagine the infectious enthusiasm of the staff contributes as much to such happy outcomes as their knowledge and authority.

This enthusiasm has since spilled beyond the murs. In 2008, the duo opened a little pub, La Capsule, just around the corner at 25 rue des Trois Mollettes. With 10 draught beers and approaching 150 bottles, including cellar aged examples, it’s one of very few bars in the city to showcase regional brewers rather than big brands. It also offers monthly tastings and food pairing events.

Late in 2011, the business expanded again with a bigger venue called the Monk’s Café, a bar restaurant in the heart of the modern day city centre at 3 rue Nicolas Leblanc. A further opening is planned for 2012, with live music promised alongside more beer.

Abbaye des Saveurs, Lille The expansion reflects how the growing craft beer movement is revitalising interest in beer even in the traditional brewing regions of Europe, coupling a concern for heritage and local production with a broad appreciation of flavour fuelled by international brewing culture. “We’ve been very successful,” concludes Franck, “because people want to drink beers with true taste, with bitterness or sourness, with full flavour and aroma.” Louis Pasteur would be delighted.

Researched November 2011.

Fact file

Address: 13 rue des Vieux Murs, 59000 Lille

Phone: +33 3 28 07 70 06

Web: www.abbayedessaveurs.com

facebook: Abbaye Des Saveurs

Hours: 1100 (1400 Tue)-1900 (1330 Sun, closed Mon)

Drink in? No, only in nearby pub

Mail order: Yes, via website

Manager’s favourites: 3 Fonteinen oude geuze, Proef/Craig Allan Cuvée d’Oscar, Saint-Glinglin and Kaou’ët beers

Beer picks

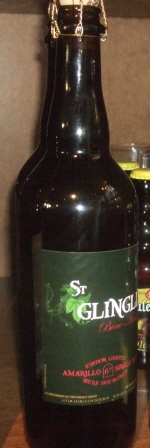

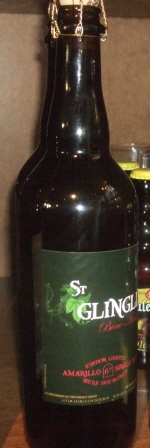

- Artésienne St Glinglin Édition Limitée Amarillo 6% Auchy-les Mines, Pas-de-Calais, France

- Pays Flamand Anosteké Brune Imperial Smout 8.5% Blaringhem, Nord, France

- Proef/Craig Allan Cuvée d’Oscar 7.5% Lochristi, Oost-Vlaanderen, Vlaanderen

- Theillier Bavaisienne Ambrée 6.5% Bavay, Nord, France

- Thiriez Blonde d’Esquelbecq 6.5% Esquelbecq, Nord, France

Beer sellers: Abbaye des Saveurs

ABV: 6%

Origin: Auchy-les Mines, Pas de Calais, France

Website: http://biereartisanale.fr/

Artésienne St Glinglin Limited Edition Single Hop Amarillo You’ll look in vain for the delightfully assonant St Glinglin (pronounced like ‘san-glan-glan’ but with French nasalised vowels) in the Dictionary of Saints. When a French speaker says something will happen on St Glinglin’s day, it’s a humorous way of saying it won’t happen at all, similar to English expressions like ‘when pigs fly’. When Thomas Pierre chose to label his first commercial beers after the nonexistent holy man, he was deliberately digging at breweries that fake monastic credibility with the names of fictitious or defunct religious institutions.

Such irreverence is characteristic of a brewer still in his late 20s, who moved from garage brewer to professional in 2007 on a budget of a mere €50,000. He’s succeeded through quality, flair and an iconoclastic imagination, catching attention with a cannabis beer called Weed alongside new twists on more familiar styles.

Une jolie verre de St Glinglin This superb special edition, recommended to me refermented in a 750ml bottle at the Abbaye des Saveurs beer shop in Lille, is one of an occasional series taking Thomas’ basic St Glinglin blonde recipe but with a single hop – in this case the distinctive and fashionable Pacific Northwest variety Amarillo, yielding a fusion between Flemish abbey blond and hop-accented American pale.

My bottle poured clear and very pale golden with a fine bead and a thickish, very tight white head. An inviting and distinctive aroma had notes of apricot, black pepper, roses and grass. The palate was crisp but full with plenty of herbal and fruity complexity, apricot, tobacco, honey and lemon with faint notes of detergent and burnt dried fruit. Salad green bitterness emerged in the mouth and developed in the lingering finish, but wonderfully softened by fruit, with a rush of juicy orange, and more apricots and pepper.

It would have been unthinkable a decade or so back for such a vivid and unusual beer to emerge from a Northern French brewery – so maybe St Glinglin has his day after all.

Beer sellers: Abbaye des Saveurs

ABV: 6.5%

Origin: Esquelbecq, Nord, France

Website: www.brasseriethiriez.com

Thiriez Blonde d'Esquelbecq Daniel Thiriez began reinventing Northern French beer as far back as 1996. He ploughed a lonely furrow for some years – only from the mid-2000s have other startup breweries in the region dared to brew beyond established traditions. But Daniel maintains a commanding position with his world class beers, several of which I’ve written about elsewhere on this site.

Blonde d’Esquelbecq is his best seller, a tasty and distinctive but accessible blond beer that’s a great first step in exploring the newer beers of the region. Named for the village where the brewery is based (from an old Dutch name meaning ‘acorn brook’), the beer is brewed whenever possible from local barley malted at the Château du Soufflet, with bittering hops from Flanders and aroma hops from the Czech Republic. The yeast originally came from Brussels, and the beer is conditioned for at least three weeks at the brewery before being reconditioned in the bottle with fresh yeast and sugar.

A 330ml bottle bought in late 2011 at the Abbaye des Saveurs in Lille poured a hazy gold with a fine white head and mineral malt aroma with suggestions of coriander (though I’ve no evidence the beer is spiced) and some slightly phenolic, medicinal notes. Those mouthwashy phenols persisted, if gently, on a very creamy, fresh, quite clean and malty palate, with notes of citrus and grassy, gently spicy “noble” hops. The finish remained coating, creamy and full, with more citrus and hops and a building nugget of bitterness. A perfectly poised blond with extra interest from more complex flavours.

The recipe has been tweaked slightly very recently and the beer, and an alternative English language label, simply reading Thiriez Blond, now declares only 6% ABV.

ABV: 4.5, 6.4 and 7.2%

Origin: San Francisco, California, USA

Website: http://thirstybear.com

ThirstBear Brewing Company and Spanish Cuisine, San Francisco Northern California’s Bay Area is indisputably the birthplace of the modern US craft brewing movement, whether you date it from Fritz Maytag buying and reviving San Francisco’s historic Anchor brewery in 1965 or Jack McAuliffe founding the first US microbrewery of the modern era, New Albion, in Sonoma in 1976. Inspired in part by the atmosphere of nonconformism and experimentation that the principal city and its outlying region has nurtured since at least the 1950s beat scene, when Kerouac and Ginsberg hung out at Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s North Beach bookstore City Lights, Bay Area brewers have moved in all kinds of weird and wonderful directions – think of Drakes, Lagunitas, Moonlight, Moylans, Napa Smith or Russian River.

Compared to that lot, often overlooked San Francisco brewpub ThirstyBear seems, well, more grounded – but the quality and the ambition are just as keen as among the purveyors of three-figure IBUs and menageries of wild yeast. It’s a stylish place in the City’s SoMa neighbourhood – so named as it’s south of the diagonal axis of Market Street.

The area was formerly, and remains partly, industrial, with a reputation that dates back at least to the beginning of the last century of catering to itinerant workers and the homeless — still a disturbingly common sight on the city’s streets for all its liberal values and prosperity. Today’s SoMa is a slightly edgy mix that includes major cultural institutions like the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Yerba Buena Center, galleries and craft shops, the Moscone Center with its high tech trade shows, the cruisier side of the local gay scene along Folsom Street and a world class beer shop, City Beer Store.

Iconic Spanish imagery at the ThirstyBear. The brewpub’s founder, former immigration lawyer and all round bundle of energy Ron Silberstein, conceived the place as a way of combining two of his passions when he opened it in 1996 – a home brewing hobby he’d acquired as a student in Massachusetts in 1978, and a love of Spanish food, especially tapas, that developed during a two year sojourn in Madrid in the 1980s. As brewpubs boomed in the 1990s, Ron chucked in his job and joined the first cohort on the American Brewers Guild’s Intensive Brewing Science and Engineering Diploma.

Fermentation vessel at the ThirstyBear. As well as all the other aspects of running the business, Ron did all the brewing in the early days and developed many of the core recipes. But trade grew and pressure on time increased, and in 2002 he took on a full time brewer, the garrulous Brendan Dobel, another former home brewer who served his professional apprenticeship at Tabernash in Colorado (since absorbed by Left Hand). Brendan then trained at the Doemens-Akademie in Munich, and worked at the Fässla brewery and the famous Weyermann maltings in Bamberg before returning to his native California determined to brew German-style beers. Which he still does to an extent, and the influence is clear, but it’s not the overarching theme of the Bear.

The original concept was to give equal weight to food and beer and food remains a strong part of the offer. The place has a claim on being the first authentic contemporary Spanish restaurant in the USA and includes on its menu well cooked version of traditional staples like paella (including one with locally foraged wild mushrooms), pescaditos fritos, empanadas de polla and membrillo. But there are also burgers, bar snacks and Californian artisanal cheeses, and you’re welcome to pop in just for a drink at the bar. Despite the “Please wait to be seated” sentry at the door, the contemporarily styled, split level quasi-industrial space with its long tables, bare brick and bullfight posters still has the sociable, bustling feel of a bar more than a restaurant.

Casks at the ThirstyBear. Brewing takes place in the extensive basement but the tall conico-cylindrical fermenting vessels tower impressively, penetrating through to the public space. The design is as it was on first opening and Ron says he would do things differently now, as some of the kit is hard to access and the layout doesn’t make the best of the brewhouse as a feature of interest for customers, but it’s certainly capable of producing some very decent beer. In the grain store I spotted supplies from Brendan’s former employer Weyermann, Gambrinus in British Columbia and from Crisp in the UK, but the brewery also makes use of more local supplies – it has brewed beers made entirely from California-grown malt and hops. All the ingredients are organic – it is the first and so far the only San Francisco brewery certified by the state accreditation body CCOF.

The name, incidentally, has nothing to do with the bear on the California state flag but is taken from a headline in the San Francisco Chronicle which caught Ron’s eye in 1991, “Thirsty bear bites man’s hand for beer”, recounting an incident in the Ukraine when an escaped circus bear had attacked an unfortunate drinker, one Viktor Kozlov, and took his beer. The victim is commemorated in the regular stout, Kozlov Stout. This is one of seven regular brews that also include a pils, a brown ale that aims at a British rather than a contemporary US style, an IPA and a Belgian-style wheat beer. All are unpasteurised and usually served from kegs and bright tanks, with the stout and ESB dispensed nitrokeg style, but the brewery also experiments with wood ageing and usually offers at least one cask beer, sometimes a cask version of a regular.

Glasses for quenching bear-sized thirsts. Taster fights with small glasses of all the available beers are sold, and I worked my way round one, picking out a few to write about in more detail. ThirstyBear’s brews aren’t “extreme” beers – they’re by and large very flavoursome and well made, but also approachable, balanced and not too assertive, very much reflecting the original intention of creating quality beers to match with food. Well worth seeking out, even if you don’t have a bear-sized thirst.

Golden Vanilla is the lowest gravity of the regular brews and one of the pub’s most popular lines, a delicate golden ale, shading on light amber, that’s infused during conditioning with whole organic vanilla pods. Vanilla is obvious on the aroma and also on the palate, giving a cream soda note but remaining dry rather than sweet, with some tangy fruit and biscuity malt. The shortish finish develops very gentle hop notes – the beer is only rated at 15 IBUs. This is a light hearted, easy quaffing beer with a subtle twist and you can see why they get through so much of it.

Meyer ESB is ThirstyBear’s entry in the extensive ranks of US craft beers honouring England’s, and more specifically Fuller’s, Extra Special Bitter style. Like many other examples it’s a bit stronger than the original at 6.4%. It’s fermented with Wyeast’s ‘1968’ classic British ale yeast strain and is habitually served stout-style using nitrogen but occasionally pops up in cask.

Firkin Tuesday at the ThirstyBear (firkin puns thankfully avoided). My sample was a rich amber with a fine, dense yellowy-beige head and an aroma of fruit, malt and cream. The palate was big but very smooth and rounded, with that sweet-dry ambiguity I find characteristic of the original. Again there was fine biscuity malt, with some slightly stewed, earthy hop flavours coming through – the bitterness is rated at 30 IBU. A coating and very moreish finish had a light but not overbearing bite of hops. Overall this was my favourite of the beers I tried.

There are regularly changing seasonals and specials and when I called they were serving Ryeison, a saison-style beer made with rye. This came about as a result of one of those homebrew competitions where the prize is to have your beer made by a professional brewery. It was a golden beer with a bit of white head. A fruity and notably soured aroma heralded a soft but complex palate, with typical oily and spicy rye flavours, aromatic orange notes, some gritty malt and a hint of vanilla. A sweetish, fruity finish dried to leave tangy orange marmalade and herbal flavours.

Shopfront at the Beermongers, Portland, Oregon, USA Portland, Oregon, is a beautiful, prosperous, civilised inland port city straddling the Willamette river. Looking west from the riverside, across a fine strip of parks and beyond the traffic calmed city centre with its free public transport, elegant squares and compact walkable blocks, thickly wooded slopes climb steeply, forming one of the USA’s largest and lushest urban forest parks. Besides fine views and many miles of surprisingly rugged trails, it boasts a zoo and a world famous rose garden, and you can reach it on a modern light rail system, only a few stops from the urban centre of Pioneer Courthouse Square.

Just to the north the Willamette drains into the Columbia river which divides the state of Oregon from neighbouring Washington. Tumbling from the Cascade mountains on its way to to the Pacific, the Columbia has carved a spectacular gorge 130km long and up to 1,200m deep, now protected as a National Scenic Area.

Sean Campbell pours a beer at the Beermongers, Portland, Oregon. So though it’s some way down the list of famous US cities, Portland has much to reward the discerning visitor – and even more so if one of your interests is beer. Oregon is one of the cradles of US craft brewing, home to some major names with their roots in the early growth of the movement in the 1980s, like Deschutes, Full Sail, Rogue and Widmer Brothers, this last in Portland itself.

The state is now the second largest craft beer producer and the third largest craft beer market in the country. And as its biggest city, Portland is a major focus of the industry, hosting Oregon Craft Beer Month in July and boasting 43 breweries, more than any other city in the world.

Readers who know their hops will pick up a clue to one of the reasons for such beery excellence from some of the geographical names mentioned above. Both the Willamette and the Cascade range lend their names to hop varieties, reflecting the state’s longstanding importance as a hop growing region, now the second biggest hop producing state in the US.

Full Sail Session Lager at the Beermongers Decent beer here has become a commonplace – even tiny local delis offer a selection of craft brewed bottles and cans. Amid such abundance, it’s more of a challenge than usual for specialist outlets to stand out, but one place that really makes an impression is the BeerMongers, one of the city’s most youthful beer venues.

The format combines a shop and a bar – a setup that’s becoming more widespread on the US scene and is also employed by another excellent Portland venue, the older-established Belmont Station, not far away. But whereas Belmont splits the space between the two functions, at the BeerMongers they coexist in a single space.

It’s in southeast Portland, some way from the city centre – I took a long walk there on a warm early autumn day, across the river and southeast following the railroad tracks, but it’s also by a bus stop with a frequent and reliable service. It’s set back from the road in a row of industrial units clustered around a little car park.

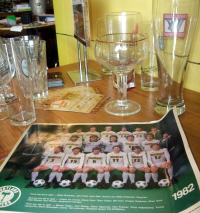

Rare and empty bottles at the Beermongers The interior of this rather smallish and rather anonymous concrete space has been turned into something that’s homely and amicably cluttered, with a mix of art, sporting ephemera and breweriana on display. An assemblage of beer bottles and cans, both vintage and contemporary, has been donated by local collectors, including a 1979 sample of the first commercial bottling of Anchor Old Foghorn, courtesy of veteran Anchor brewer Ron Wolf, who now works for local brewpub chain McMenamins and occasionally serves behind the bar at Beermongers events.

The McMenamins connection extends to cheerful and enthusiastic chief beermonger Sean Campbell, who has worked for the bigger company for 15 years and continues to do so, splitting his time with his own business. He and his business partner wanted their own beer-related project and first thought of a brewery, but decided there was too much competition already. Speciality beer stores, however, were relatively rare. “Where I live, there are three wine shops I can walk to but nobody does a good range of beer, even though everyone drinks it,” says Sean.

Well-stocked fridges at the Beermongers. Besides the large fridges containing around 525 bottled beers that line two walls, there are also eight draught taps – a relatively small number by US craft beer bar standards but vital nonetheless and well tended by Sean and bar manager Josh. “We always intended to have in-store consumption when we opened in 2008,” Sean explains. “The law in Oregon allows it so long as we don’t allow minors or serve hard alcohol.”

Originally the stock was just bottles, sold at the same keen prices both for drinking in and out, a policy which happily endures. “But as the first year went on,” Sean continues, “we got this really great group of customers that wanted to spend more time here, so we got the bar built and added more seating, and people have taken to it as a place they like to hang out. And that’s great – I’ve always liked working behind bars and chatting to people. I used to live in England and worked in pubs there. Not having too many taps means we focus on specials and seasonals, often from small local brewers, and we can give each beer the attention it deserves.”

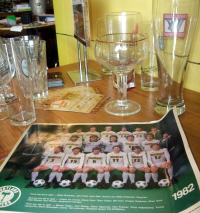

Sean’s professional background explains a slight British touch to the decor – there are some second hand English church pews his parents found for him, and most of the woodwork was created by a British expat carpenter. Displays that honour the popular local proper football – as in soccer – team, the Portland Timbers, add to the effect.

Glasses and real footie at the Beermongers The beers are arranged not, as is usual, by country and region but by style, irrespective of origin, creating some interesting juxtapositions that invite comparison and contrast. So Belgian classics like Saison Dupont line up beside American interpretations from small Oregon brewers like Ambacht, Beetje, Logsdon, Upright and the puzzlingly named Captured by Porches, while fellow Oregonians Southern Oregon and Fort George challenge Bitburger and Budvar in the pils section.

Belgian-style and genuine Belgian beers are well-represented beyond saison, with lambics from 3 Fonteinen, Boon and Hannsens and big ales and sour browns from Anker, Rochefort, St Bernardus, St Feuillien, Verhaege and lesser known names such as Gaverhopke and Schelde. These are ranged alongside American tributes and variations from the likes of Deschutes, Pelican (both from Oregon), Avery, Anchorage, Boulevard, Green Flash, Nebraska and the always appreciated but hard to find Russian River.

Still, US beers dominate, and as you’d expect, pale ales and IPAs are particularly well represented. Other small Portland brewers on the shelves include Alameda, Hopworks and Lompoc while 10 Barrel, Beer Valley, Caldera, Flat Tail, Hop Valley, Klamath Basin, Ninkasi, Oakshire, Pelican, Seven Brides and Silver Moon come from elsewhere in the state. Other West Coast brews – Diamond Knot, Fish Tail and Pike from Washington, Bison, Green Flash and Uncommon from California – line up beside admired craft brewers from across the nation. The cultish Pabst Blue Ribbon is a sole ironic nod to the mainstream, a survivor from the early days when they also offered a range of national brands but found most of them ended up in the bargain bin.

Imported offerings besides those already mentioned include Scandinavian eccentricities from Beer Here, Evil Twin, Midtfyns, Mikkeler and Xbeeriment; some British classics from Fuller’s, JW Lees and Traquair; and the odd bottle or two from Canada, Italy, the Netherlands and Japan. A small range of craft ciders is set to expand as local interest in this sector grows.

The range includes some beers the management admits are relatively slow sellers “Drinkers have gotten more experimental with sour beers, geuzes and other funky beers that they wouldn’t have recognised three or four years ago,” says Sean. “As soon as I start thinking, ‘why are we carrying that?’, someone will come in and say it’s their favourite. And our approach is good for brewers too – if they come up with something new they will often put it out to us because we’ll at least try it.”

Sean Campbell of the Beermongers It’s a densely populated part of town but the shop gets visits both from across Portland and far beyond, with customers from across the US and Canada, including numerous younger craft beer fans. Sean has learned not to stereotype. “Young folks who look like they just got off their skateboard might go straight for Rodenbach,” he says. Other customers are members of the city’s sizeable home brewing community, looking to try examples of styles they intend to make.

Events include regular Meet the Brewer evenings, themed days when countries, styles or regions take over all the taps, an annual Orval event and beer festivals where they expand into a marquee in the car park. Expansions are planned, such as adding aged beers (including Orval), or even opening a second branch. Good advice is on hand when you need it. “People are here for fun and the shopping experience,” Sean confirms, “so there’s a delicate balance between education and hovering.”

Online and social marketing have proved a key to success in an increasingly web-based beer scene. “We had facebook and twitter accounts right from the beginning,” Sean recalls. “It takes your time, but it doesn’t take anything out of your pocket and I don’t think we would be nearly as successful without that stuff. I’m 40 and a bit of a dinosaur as I still read the newspapers, but lots of people younger than me get all their stuff online, including from trusted beer blogs.”

Sign at the Beermongers. I spotted exceptions. Great little places like the Beermongers are currently riding the crest of a wave of excitement in fine beer, not only in places like Portland but elsewhere. Even in the midst of recession, craft beer is flourishing as an affordable luxury that people like Sean are keen to share. “It’s great to be able to tell people they can enjoy the greatest sour beer in the world for less than $20,” he concludes. I’ll raise a glass to that.

Researched September 2011

Fact file

Address: 1125 South East Division Street, Portland OR 97202 (corner of SE 12th and Division)

Phone: +1 503 234 6012

Web: http://thebeermongers.com

Hours: 1100-2300 (Fri-Sat 2400)

Drink in? Yes

Mail order: No

Manager’s favourites: Orval, Oud Beersel Oude Geuze, Heller-Trum Schlenkerla Rauchbier Märzen, Upright Belgian-style beers

Beer picks

All from Oregon

Beer sellers: Beermongers

ABV: 5.4%

Origin: Pacific City, Oregon, USA

Website: http://pelicanbrewery.com

Pelican Kiwanda Cream Ale US craft brewers, particularly West Coast ones, are known to beer fans in Europe primarily as producers of extreme beers – hyper-hopped, ultra gravity, wild fermented monsters that have preferably spent two years maturing in a bourbon barrel. But the truth is most brewers pay the rent with much more everyday and approachable brews that shade towards what Brits might recognise as session beers, and in my view these are at least as interesting, particularly those that look back to historic, pre-Prohibition styles.

When brewer Darren Welch was devising the initial recipes for the nascent Pelican brewpub, right on the ocean at Pacific City, Oregon, in 1996, he puzzled about what style to adopt as the entry level beer on offer. Avoiding the obvious pale ales and lagers, Darren developed a recreation of a 19th century cream ale. This style had originally developed as the old established ale brewers’ answer to the growing popularity of pale lagers from German-American breweries, using pilsner-style ingredients and a cold conditioning period but with a warm fermenting yeast, rather like Kölsch is made in Germany today. He named it after the protected coastline of Cape Kiwanda nearby.

Kiwanda Cream uses two-row pale malt, carapils malt and flaked barley, with a single hop, Mount Hood, a variety known for its German-style subtlety rather than the vivid citric and pine flavours most associated with American hops.

A 650ml bomber bottle bought at the Beermongers in Portland, Oregon, yielded a pale yellowy gold beer with a fine and full white head and a creamy and slightly spicy malty aroma with a classic hop note. The palate was straightforward but accomplished, with cracker-like malt lifted by firmly tingly and gently flowery hops. The finish left a creamy texture in the mouth, with light citric flavours and a refreshing bitter note. Overall a very well-balanced, tasty, honest and satisfying ale.

|

Cask  This pioneering new book explains what makes cask beer so special, and explores its past, present and future. Order now from CAMRA Books. Read more here. This pioneering new book explains what makes cask beer so special, and explores its past, present and future. Order now from CAMRA Books. Read more here.

London’s Best Beer  The fully updated 3rd edition of my essential award-winning guide to London’s vibrant beer scene is available now from CAMRA Books. Read more here. The fully updated 3rd edition of my essential award-winning guide to London’s vibrant beer scene is available now from CAMRA Books. Read more here.

|