Banner for the Toer de Geuze 2011 on display at 3 Fonteinen.

Snobbery aside, there are some potentially defensible grounds on which to build a case that making wine is a higher field of human endeavour than making beer. Winemakers squeeze the maximum complexity and variety from the minimum of means. From New World varietal superplonk to grand cru classé, it’s all just grapes and a huge amount of human skill, patience and experience. And quite likely those grapes were grown only a few hundred metres from where they were crushed, fermented, matured and bottled, giving the resulting wine a unique provenance, an unbroken, traceable link between the soil and climate of the vineyard and the liquid that finally glugs from the bottle. Winemakers might justifiably claim that brewers, with their huge choice of dry ingredients and their lab-reared libraries of yeast cultures, have it easy. Where is the struggle with nature, the umbilical link with the land?

But then there’s lambic.

This family of commercially produced spontaneously fermented beers, still surviving and indeed now even modestly expanding in a few pockets of Belgium, perpetuates the specific engagement with the immediate environment that was once the everyday experience of all brewers. The method still might not have quite the simplicity of winemaking, and still draws on a mix of dry materials, these days sometimes trucked long distances. But the fermentation process at its heart is as primeval as brewing gets, rejecting the legacy of Louis Pasteur and instead throwing the wort open to the elements, inviting a whole menagerie of airborne wild yeasts to infect and ferment it. The local microclimate, most notably in the style’s heartland of the Pajottenland, in the valley of the river Zenne west and southwest of Brussels, stamps its imprint on the beer through the microorganisms it nurtures. So do the casks in which the beer is matured and even the very bricks of the breweries.

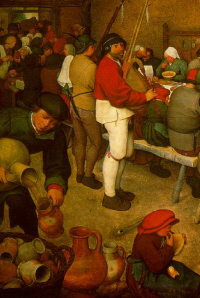

Lambic brewers like to point to the famous bucolic painting De Boerenbruiloft (Peasant Wedding) by Pieter Bruegel de Oude (1525-69), which includes a depiction of someone dispensing straw coloured beer from a large ceramic crock. There’s a reproduction of the painting on display at lambic blenders De Cam in Gooik, next to a microscopic enlargement of assorted wild yeast cells. Appeals to centuries old tradition are of course a familiar trope in beer marketing, though rarely can the products concerned trace their history much further than the 1950s, or the 1720s at a push. But in the case of lambic, the appeal to history is almost certainly justified. Why it survived is a puzzle, but survive it clearly did, in defiance of all the trends of the industry over the past century and a half, even more of a delightfully stubborn anachronism than British cask ale.

If lambic is one of the world’s most important beer styles, then the flagship celebration of lambic brewing, the Toer de Geuze, must be one of the world’s most important beer events. Shame on me, then for being so tardy in parcipating, but the event’s infrequent timing, on the first Sunday in May of odd numbered years, has caught me out until now. It’s organised by HORAL, or Hoge Raad voor Ambachtelijke Lambiekbieren, which translates rather pompously into English as ‘high council for craft-brewed Lambic beers’ but is simply the trade association for lambic brewers and blenders in the Pajottenland and Zenne valley. They work closely with the volunteers of De Lambikstoempers, the local affiliate of Belgium’s beer consumer organisation Zythos.

The Toer, which has just been mounted for the eighth time, is essentially a doors open day for the lambic industry. HORAL members throw open their doors for brewery tours, tastings and beer sales, with catering, live music, bouncy castles and other activities completing the offer of a fun day out for all the family. HORAL organises tour buses which this year plied eight routes, each taking in five of the nine participating sites. Or you can find your own way round, with cycling a particularly popular mode of travel. Other organisations also lay on transport — commercial operator Podge’s Belgian Beer Tours and Dutch beer consumer organisation PINT were among those out and about this year. The bars and tastings are an excellent opportunity to try the various HORAL members’ straight lambics, most of which usually end up in blends.

With little idea of what each brewery might offer the visitor, I spent €12.99 prebooking HORAL’s bus route 1, which was covering a couple of my favourites and a couple I was curious about. So I found myself at 1015 on a beautifully bright and sunny Sunday at Halle station, boarding a comfortable double decker coach. Welcoming me aboard was the very knowledgeable and amply hirsute Johan ‘Wanne’ Madalijns, chair of the Lambikstoempers. My fellow passengers were mainly Flemish and mainly male, though with a good range of ages, and a smattering of Brits, Dutch, Italians, North Americans and Scandinavians. The news on VRT-1, the main Dutch language TV channel, reported with some amazement that evening on visiting Americans, including Pete Slosberg of Pete’s Wicked Ale fame. But it was reassuring to see so much national support for a beer style which only a couple of decades ago was on the brink of extinction.

Indeed this was a very Flemish occasion and I was glad of my Dutch skills. Lambicland largely falls within Vlaams-Brabant, in the Dutch speaking part of Belgium, which wraps to the south of the officially bilingual but predominantly francophone Brussels Capital Region as a narrow strip separating it from French-speaking Brabant-Wallonie. All the lambic enterprises are in Flemish territory except Cantillon in Brussels, not a HORAL member, and the soon-to-launch Tilquin, of which more in a later post. As we approach, Wanne introduces each brewery in Dutch, asking people to translate if necessary for their neighbours. Most of the brewery tours are also conducted in Dutch, though the guides happily deal with individual enquiries in English.

This is one of Europe’s most populated areas, and no more than ten minutes on the train from the busy international rail interchange of Bruxelles-Midi, but the surroundings are surprisingly rural, and attractively lush and green in the sunshine. Rolling lanes run between small woods and fields where Belgian Blue cattle graze, and our coach is clearly uncomfortable in the narrow streets of the villages that liberally dot the landscape.

First stop is De Cam, attached to a community centre, musical instrument museum and bar in the village of Gooik, the self-proclaimed ‘pearl of the Pajottenland’. The building dates from 1515 and was a brewery in a former incarnation — the name is an old dialect word for brewery. The current beer-related activity is more recent, dating from 1997 when Karel Goddeau set up shop as a lambic blender, buying in lambics from Boon, Girardin and Lindemans and brewing himself at 3 Fonteinen. Karel welcomes us and explains how the unusual process of lambic production facilitates such collaborations.

Wild yeasts typically ferment slowly, and the resulting product is too acidic to drink when young, so the beer is matured in wooden barrels, both to complete its fermentation and to round off the rough edges. Age is usually quoted in years but strictly speaking it is measured in summers, reflecting the seasonal cycle of lambic brewing, which is only practical in cooler weather. Beer is aged for one or two summers, occasionally for three or four. Given the unpredictability of the wild yeast, consistency is achieved through blending, and palatability is also enhanced, famously, by steeping fresh fruit in the beer.

There’s no reason why maturation, steeping and blending can’t take place in a different location from the one where the beer was brewed, creating openings for specialist blenders, known in Dutch as geuzestekerijen. Day old beer, already colonised by the local yeasts, is transported in bulk from the brewery to the stekerij, where it’s placed in large oak barrels or tonnen. These are normally venerable old vessels that have been reused many times – most of those at De Cam are 1,000l capacity vats that were originally used for lagering at Plzeňský Prazdroj (Pilsner Urquell).

De Cam proudly displays a local CAMRA Beer of the Festival award.

“Lambic,” says Karel, “is the mother of all beers,” recounting that it can be traced back in the Pajottenland at least to the year 1400, while the sparkling blend of lambics known as geuze (gueuze in French) was perfected from the 1820s. “Lambic is basically a flat beer, “ he tells us, “so for geuze we ferment year-old lambic with three- or four-year-old beer. The younger beer wakes up the fermentation and the older one cools it down a bit. It all depends on temperature, acidity and nine different microorganisms, including brettanomyces.

“Everything in the bottle is wholesome and healthy,” he continues, “and there are less calories in a bottle of our geuze than in a glass of milk. It’s full of antioxidants, which also protect it – geuze will keep for 20 years after the bottling date. If you have a cellar with a constant temperature of 10-12°C, lay down a couple of bottles of geuze every year, and within twenty years you’ll have heaven on earth in your cellar.”

Karel’s geuze, like nearly all the best examples, meets the protected European definition of oude geuze (oude meaning ‘old’), containing 100% spontaneously fermented beer with no additional sugar, unpasteurised and fermenting in the bottle. The cherry-steeped kriek is similarly designated oude, with 900kg of sour cherries added to 1500l of lambic. The traditional Belgian fruit variety used, Schaarbeekse krieken, named after Schaarbeek, a former village just to the north of Brussels city centre, are sometimes not available in large enough quantities so morellos from Limburg are substituted, or if necessary frozen sour cherries from Poland.

De Cam is a relatively small operation, essentially a barn with a blending vessel and all those Bohemian vats quietly doing the business. The tour ends with a free tasting from the bar in the adjoining café, where an impromptu band performs a folksy jam on guitar, accordion and bagpipes, the last another echo of Bruegel’s wedding scene.

Next up is De Troch, one of the most fascinating stops on the tour. It’s best known for its extensive range of sweetened low gravity concoctions of lambic and exotic fruit juices under the Chapeau brand, which hasn’t endeared it to fine beer enthusiasts, but it has one of the longest pedigrees of all the surviving lambic breweries. Dating back to the early 18th century and clustered round a courtyard next to an associated drinks warehouse in the centre of the village of Wambeek, its buildings certainly look the part of the village family brewery. The small first floor brewhouse was spring cleaned in 2004 following a health scare but is still creaky and cobwebbed, with light shining through gaps in the tiled roof above. “Think how much water is in your beer, madam” quips our guide to a visitor who points this out.

A remarkably small mash tun (roerkuip in Dutch) from the 1930s, the oldest of its type still in use, is employed to mash barley malt, mainly pale but with a smattering of darker malt, and unmalted wheat – a 1986 law specifies at least 30% wheat must be used in lambic. The mashing temperature is raised in five steps between 45° and 78°C to achieve optimal release of enzymes. Next the wort is boiled in copper kettles with considerable quantities of aged hops, mainly from the Czech Republic with some from Germany, which retain their preservative and stabilising qualities but without the bitterness and aroma that would clash with the sourness of the finished beer. The brew is then filtered and run to the immediately adjacent steel lined koelschip, the characteristic broad, shallow vessel resembling a paddling pool in which the fresh wort is left to consummate its union with the local microflora. This requires it cooling to a temperature less than 18°C, or ideally under 15°C, therefore the limitation on summer brewing.

Before it earns the designation lambic, the wort has to spend a few months in wooden vats, of which De Troch has an extensive magazine, each one lending its contents an individual character. At six months it might be used for fruit beers or as part of the geuze blend, but De Troch ages lambics for up to three years, including for use in its oude geuze, Chapeau Cuvée. “Once people were happy to drink sour lambics,” says the guide, “but then they wanted sweeter and sweeter beers. Now it’s changing with demand going back towards sour beers again.” Good to hear in a lovely old brewery which still doesn’t quite live up to its potential.

Then we’re off to the village that gave its name to the style, Lembeek, and to Boon, the biggest and best known establishment on my trip. Frank Boon first blended lambic in 1975 when he bought the old De Vits brewery at Halle, moving into brewing in 1990 and shortly afterwards expanding into this former metalwork factory, literally on the banks of the infant Zenne. It operates in partnership with national brewer Palm, but Frank has retained credibility while pursuing commercial success, notably in the export market, and is recognised as one of the saviours of lambic.

It’s lunchtime and Boon’s extensive site is thronged with people enjoying beer, sausages and roast meat (nothing for veggies – I end up resorting to a packet of crisps and a plate of cheese at one of the village pubs), music and brewery tours conducted with impressive efficiency by a small army of brand-compliant guides. Inside the brewhouse, a red-painted mash tun is in action, its rotating blades lazily stirring a steaming porridge of barley and wheat. Given the warm weather I guess this may have been laid on for the visitors.

Boon boasts a generously proportioned koelschip, alongside some extensive blending vessels and a fine collection of oak tuns, some of which are gigantic, with a capacity of over 7,000l, big enough to hold a small drinking party in. No simple bungs here – the biggest tuns are accessed using chunky metal devices that might challenge the skills of a professional safe picker. The three-year-old lambic we’re offered straight from one of these is absolutely divine, one of the most extraordinary beers I’ve ever tasted.

Our final calls are both in Beersel, another important lambic village, though its name looks curiously appropriate only to English eyes. Sadly the Toer is a fortnight too early for its new Lambic Visitor Centre, due to open on 15 May. The village, atop a steep hill climbed by a winding lane that seriously challenges our coach, is also famous for its distinctive castle, once the seat of the Seneschal of Brabant.

I’m looking forward to 3 Fonteinen, territory of another legendary saviour of lambic, Armand Debelder. His family owned a pub in the village since 1953, one of the few to perpetuate the once common tradition of maturing and blending its own geuze, and Armand developed these blends into a well respected brand. In the 1990s, fearing that the rapid decline in the industry threatened future supplies, the company began to brew its own lambic, but in 2009 a faulty thermostat destroyed much of the (uninsured) stock of maturing bottled lambics and the financial impact of this has seen them scaling back to a simple geuzestekerij again for the foreseeable future.

In the event I’m disappointed as there’s not much to see, with no tours of the old brewery or maturation rooms. The narrow yard is uncomfortably packed with visitors, with several coach parties arriving at once. Somewhere in the throng is celebrity chef Jeroen Meus signing copies of his latest book Dagelijkse Kost (‘Everday food’). For the occasion he’s devised an interpretation of the traditional lambic beer snack, plattekaas, a mild, white and foamy local cream cheese spread on a big slice of farmhouse bread. Normally this comes with spring onions and radishes, but the boterham Jeroen Meus is flavoured with horseradish and honey, spinkled with walnuts and garnished with fresh watercress from nearby Loonbeek. I squeeze into the slightly quieter surrounds of the adjoining tasting room, the Lambikodroom, to try one with a geuze – the combination works well but I miss the crunchy radishes.

On the other side of the village is Oud Beersel, formerly the Vandervelden lambic brewery, established in the 1880s – Oud Beersel became its principal brand. Closed in 2003, it was reopened shortly afterwards as a blender and brewing museum by Gert Christiaens, and its current form is partly the result of winning a makeover programme on TV. It’s an atmospheric old place, with two old cylindrical brewing vessels and a koelschip under the authentically cobwebbed eaves, and displays of old brewers’ and coopers’ tools, but they’re for display purposes only. Gert has attracted some criticism for labelling the place a brouwerij when all the beer is brewed and seeded, using Vandervelden recipes, at Boon.

The maturation rooms are still very much in business: the fresh beer is tanked from Lembeek to develop in 500l oak tuns, some of which were previously used for port and are up to 50 years old. Guide Christiaan Robeyns explains how a wide choice of lambics is needed to ensure a consistent blend, as inevitably with spontaneous fermentation, each brew will be slightly different. He also shows us the historic installation that cleans the tuns with a combination of high pressure water, sulphur dioxide and metal chains to scour the inner surface.

I enjoy a final lambic across the road, where a temporary collection of bars, food stalls, tables and chairs and yet another bouncy castle is doing brisk business. Then we’re back in Halle and Wanne is wishing us all goodbye and see you in two years. VRT-1 reports that this year’s Toer de Geuze was more successful than ever, with more than 8,000 people in attendance and the HORAL buses selling out weeks in advance. The success is well deserved as this crash course in the wonders of Lambicland must be one of the world’s most unique beer events, giving you a genuine sense of how geography, history and culture are fused in the creation of one of our most extraordinary and precious beer styles.

Beer picks

- Boon Oude Lambik 3 jaar oud 6% Lembeek, Vlaams-Brabant, Vlaanderen

- Cam Oude Lambiek 1 jaar oud 5% Gooik, Vlaams-Brabant, Vlaanderen

- Oud Beersel Oude Lambik 1 jaar oud (Boon) 5.7% Beersel, Vlaams-Brabant, Vlaanderen

- Troch Oude Lambik 2 jaar oud 5% Wambeek, Vlaams-Brabant, Vlaanderen

More information

- HORAL www.horal.be

- De Lambikstoempers www.lambikstoempers.be

- VRT-1 news report http://youtu.be/RmlRe0b9knk

- Lambicland, the definitive guide to lambic beers, 2nd edition, by Tim Webb, Chris Pollard and Siobhan McGinn. Buy from Amazon.

Leave a Reply