A collaboration brew is a chance to create something out of the ordinary. Among my competitors, Pete Brown has gone for a dubbel, Glenn Payne for a rye IPA and Adrian Tierney-Jones for a saison full of C-hops.

Choosing an unassuming, straightforward style is probably tying one hand behind my back, though I’m comforted to note that Sophie Atherton, bless her, has made a similar decision – she’s brewed a classic Munich-style Märzen, and rather good it is too.

And my choice is at least a beer that’s rarely attempted in the UK, despite its obvious affinity to British brewing traditions. I want to brew a spéciale belge.

Spéciale belge is an everyday Belgian pale ale that could be described as like a British bitter but with a Belgian twist, at a moderate strength of no more than 5% ABV. The best examples are amber or copper in colour, with a similar biscuit malt character to a good bitter but typically less hoppy and with a fruity, spicy note from the yeast.

The classic example is De Koninck, which is to Antwerp what Guinness is to Dublin or, indeed, what Brains is to Cardiff. It’s served by default in a goblet-shaped glass known as a bolleke, which always raises titters among British English speakers but simply means ‘little ball’.

Beer hunter Michael Jackson loved De Koninck: on his first ever visit to Belgium he “lost an afternoon” drinking it in a backstreet Antwerp pub that he never managed to find again. I love it too, particularly as an indivisible part of the experience of my favourite Belgian city.

Like many aficionados, I head for Den Engel, the classic bruin café on the Grote Markt, renowned for the freshness of its beer, and enjoy a bolleke looking out on the astonishing 16th century stadhuis (city hall) with its mix of Gothic and Renaissance styles, and the fountain depicting Brabo lobbing a giant hand at the river. More of him later.

There are other examples. Palm from Steenhuffel is the best seller but I find it slightly bland and oversweet. Special De Ryck, from a small family brewer in Herzele, is a deliciously authentic example but hard to find, as is the similarly old fashioned Tonneke from Contreras. Zinnebir, from the excellent Zennebrouwerij/Brasserie de la Senne in Brussels, is a poised and accomplished modern interpretation.

The similarity to English ales is not accidental. By the end of the 19th century, imports from the UK, as well as Germany and Bohemia, had become very popular among Belgian drinkers.

The domestic industry was not well placed to challenge this competition, as Belgian brewers rarely looked beyond local sales, producing idiosyncratic local and regional styles that were appreciated by drinkers used to them but were less than ideal material for building the sort of mass market that was already enriching brewers elsewhere.

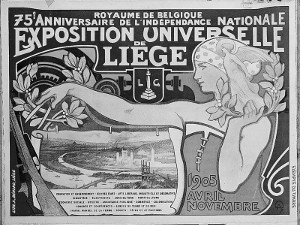

The Exposition Universelle in Liège in 1905 where the results of the competition to create a national Belgian beer style were announced also marked the 75th anniversary of Belgian independence.

In response to this, in 1904 the Unie van Belgische Brouwers (Union of Belgian Brewers, today known simply as Belgische Brouwers) organised a competition to create a new and contemporary beer that might build a following throughout Belgium. Doubtless there was also a more deeply ideological outcome in mind too – such a beer might contribute to a sense of shared national identity and unity in a nation state that was (and remains) an uncomfortable bracketing of disparate linguistic and cultural communities.

Entry guidelines were kept deliberately broad: the beer could be made using any ingredients or methods, so long as it had an original gravity of 4-5 Belgian degrees (1040-1050 original gravity) and cost 15-20 cents per glass.

The results were unveiled at the 1905 Exposition Universelle et Internationale in Liège. Out of 73 entries (including seven lagers and nine spontaneously fermented beers), the winner was Belge du Faleau from Brasserie Binard in Châtelineau, Hainaut – an easy drinking amber beer that stood out at a time when most domestic products were wheat beers or brown ales.

The brewery is long gone but its beer left a long legacy, as many other Belgian breweries gradually began to copy it, often appending the adjective belge to the results. De Koninck’s version was launched in 1913; Palm is a relative latecomer, from 1928.

Today’s examples are relatively few – the huge growth in popularity of pilsner-style beer following World War II devastated pale ales just as it did the wheaty, dark and wild beers those pale ales were originally intended to supersede. This trend didn’t reverse until the growth of interest in local, artisanal and speciality beers in the 1980s and 1990s.

Thankfully spéciale belge survives as a healthy niche product. It’s now recognised officially in Belgium as a streekprodukt (regional product) and there’s an application pending with the EU for Protected Geographical Indication status.

Recipes are generally simple: pale malt and a bit of Germanic-style coloured malt, a restrained dose of some relatively traditional and unassertive European hops, and a fruity but still relatively clean house ale yeast.

De Koninck is made just from pilsner and Vienna malts, Czech & Belgian Žatec (Saaz) hops, and the brewery’s own yeast culture, which is famously also sold by the shot at the brewery tap as a chaser for the beer. There are some more elaborate recipes listed on homebrewing sites, involving black malt and all kinds of other stuff, but Brains head brewer Bill Dobson and I have agreed to keep it simple.

I’m lucky, too, to have access to the advice of two of the world’s leading craft beer gurus, brewers and writers Stan Hieronymus and Randy Mosher, both fellow judges at the Great American Beer Festival in Denver, Colorado. We hold our conversation in the appropriate setting of the brewhouse at Great Divide, at a North American Guild of Beer Writers social event.

“Where are you brewing it?” asks Randy. “At Brains? Oh, just tell them to brew one of their regular bitters or pale ales but with a Belgian yeast.”

Is it really that simple? “Well, it would probably be more authentic to use German specialty malts rather than British ones. But try using East Kent Goldings as the single bittering hop. Lots of traditional Belgian brewers use Goldings.”

Stan agrees. “The hop rate should be low anyway, but you might think about using a classic European hop for a hint of aroma, like Saaz or Hallertauer. It has to be a Belgian yeast. If you can’t get one from one of the Belgian breweries, White Labs and Wyeast have some good ones.”

Following some email exchanges and some of Bill’s own research, he devises a final recipe. Ideally we’d use pilsner malt but we settle for ease on Brains’ regular stock of Simpsons Perle pale malt from the big silos in one corner of the brewery yard. We’ll use a mix of Weyermann Munich malt and caramalt to deepen the beer, Goldings as the bittering hop and a mixture of Goldings and Žatec as a late addition for aroma.

As to the vital choice of yeast, we consider White Labs’ appropriately titled Antwerp Ale Yeast, but Bill in the end picks Wyeast’s Belgian Ardennes strain (3522).

Here’s the grist bill for an initial mash with about 7.5 barrels (1250l) of liquor (water):

- 300kg (66.7%) pale ale malt

- 100kg (22.2%) Munich malt

- 50kg (11.1%) caramalt

Following sparging, for a total wort volume of 17 barrels (2780hl), we’ll add:

- 2kg East Kent Goldings as a bittering hop at the beginning of the boil

- 1kg East Kent Goldings and 1kg Žatec as a late hop at the end of the boil

To get the right strength of around 5% ABV, we’re aiming for 2.5l of liquor for every 1kg of malt.

The Brabo fountain outside the Stadhuis on the Grote Markt in Antwerp, Belgium. Note the water-spouting severed hand. Pic: Ph.Viny, Wikimedia Commons.

Oh, and then there’s the name. It crosses my mind to suggest Brains Bolleke, but I can see myself accused of bringing the industry into disrepute with schoolboy humour and shamefully vilified on Pump Clip Parade, the online rogues’ gallery of misadvised beer branding. So my mind goes back to that statue of Brabo on the Grote Markt in Antwerp, sculpted by Jef Lambeaux in 1887.

Low Countries folklore is full of stories of giants, or reuzen in Dutch, a particularly frightening notion in such a flat landscape. One such reus, by the unlikely name of Druon Antigoon, guarded the river Schelde at Antwerp, extorting tolls from people crossing the river. He was notorious for cutting off the hands of those who couldn’t or wouldn’t pay, and throwing them into the water.

The giant was finally slain by a brave Roman soldier, Silvius Brabo, who exacted poetic justice by cutting off and throwing away the giant’s own hand. Unreliable folk etymology attributes the name of the province and former duchy of Brabant to Brabo, and the name of the city to his deed – hand werpen in Dutch means to throw a hand, and sounds a bit like ‘Antwerpen’, the city’s Dutch name.

I doubt I will metaphorically slay my competitors, the giants of beer writing like Brown and Tierney-Jones, nor do I have any desire to amputate their writing hands and lob them in the Taf or the Thames. But Brabo still sounds a good name for a beer.

For more about the brewday itself, see the next part.

Des– Lots of similarities between English and Belgian Brewing. One of the most interesting explanations for this I’ve read recently is that the first generation of Belgian brewers (19th c), may have learned the brewing craft while living the Edinburgh area as refugees after the Napoleonic wars and took their skills home. In Belgium, the dark beer recipes are very complex, but the lighter beers are simple, just as in England. Typical Belgian high gravity yeasts make a delicious English barleywine. One big difference from UK–they use a lot of granulated (non-invert) sugar in their lighter colored beers and it produces a certain flavor tang. RE: your recipe: I would have gone with a lower flocculant, slower fermenting yeast than Ardennes, which can produce phenolic notes at times. Choice of malts and hops seems right on. English water tends toward being kind of carbonate (favoring the making of darker beers over lighter ones). Getting the water right is critical for lighter colored beers. Cheers, Tom!

Thanks for this, Tom. Actually it turned out pretty well — the result tastes to style to me without being a clone of any of the Belgian examples and it is a pretty decent drinking beer. It got a lot of good feedback too from people whose views I trust who tasted it at the British Guild of Beer Writers’ dinner last week. I was afraid the Ardennes yeast would be too strident too, thinking of brewers from that part of the world like Achouffe and Rulles, but actually it worked well, with a definitely Belgian-style fruitiness and light spice but subtle and not phenolic.

I think the most straightforward explanation for the affinities between brewing in the UK and the Low Countries (including Nord-Pas de Calais) is simply the physical proximity and a long common history of brewing that goes at least as far back as the 15th century when Dutch-speaking brewers started brewing hopped beer in England as a competitor to unhopped ale. Then there was the influx of Huguenot refugees from the 16th century, many of them from French Flanders and Wallonia. There’s all sorts of intriguing crossovers too with Flemish brown ale brewing, with the creation of sour and vinous beer through lengthy wood ageing recalling the original practice of London porter brewing.