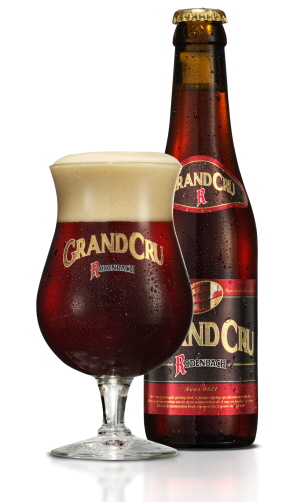

Rodenbach Grand Cru

ABV: 6%

Origin: Roeselare, Oost-Vlaanderen

Website: www.palm.be

Beer writers and experts tend to have different drinking habits from ordinary beer drinkers. To keep ourselves well informed and authoritative, we’re usually tasting beers we haven’t tried before, and find ourselves passing on the popular and familiar by. In contrast, while the number of discerning consumers prepared to experiment is growing, most people still turn to established favourites as their fall back position without the compulsion of novelty.

Of course all beer writers worth their salt have tasted the revered classics and style-defining benchmarks – but it might have been years ago, when they were honing their skills and expertise by ticking their way through Michael Jackson books. It’s a tendency I’m now trying to balance out, making a conscious effort to return with the benefit of experience to the sort of beers that sent me out on this adventure in the first place.

So it was that when on a pub review visit to Belgique Bistro, a Belgian-themed tea room and bar in the unlikely location of leafy Wanstead, last summer, I siezed the opportunity to revisit Rodenbach Grand Cru, one of the beers I used to consider a touchstone of my enthusiasm.

Rodenbach is the most prominent surviving producer of Flemish oud bruin, sometimes known in English, following Jackson, as sour red ale. The brewery’s base beer is made with Vienna malt added to the grist, which partly explains the reddish hue, and also contains a proportion of corn grits and sugar. The last time I saw the hop varieties listed they included German Brewers Gold and Kent Goldings.

It’s what happens after mashing and boiling, though, that’s most interesting. The wort is fermented with a multistrain yeast which includes lactic microorganisms contributing a lightly sour taste. It’s then matured for up to two years in a hall full of 300 giant wooden vats known as foeders, made of Slavonian oak from Poland.

These vessels vary in capacity from 12,000l to 65,000l and some of them are more than 150 years old. Each one has its own resident menagerie of microflora that adds still more complexity to the beer, including funky wild yeast notes of the sort that only appear during long maturation, which also deepens the colour still further.

To create the final product, old and young beers from various selected foeders are blended together – the standard Rodenbach uses a 50:50 mix but the more intense, and stronger, Grand Cru includes two thirds of older beer. Bottles and kegs are then flash pasteurised and sent out brewery conditioned, though some vintage specials of mature beer from individual foeders have been bottle conditioned.

Brewery historians will instantly recognise the similarities between Rodenbach’s production and classic 18th century London porter brewing, even down to the blending of ‘stale’ and ‘mild’ beers – and to the production of old and stock ales that just about clings on in England at, of all places, Greene King (see Old 5X).

The Rodenbach family, originally from Koblenz in Germany, first got involved in brewing in Roeselare in 1832, and it’s sometimes said that one of the family, Eugene Rodenbach, learned the techniques in eastern England in the 1880s. However, brewing has been a relatively international occupation at least since it first became a large scale industry, and brewers often independently evolved similar responses to similar challenges, such as keeping beer reliably consistent and palatable without refrigeration and microbiological science to help.

Whatever the truth, Rodenbach today is something of a brewing heritage treasure. In 1998 it was bought by Belgian national brewer Palm and there were intial concerns this might spell the beginning of the end for its unique products, but in fact the parent company has invested and now proudly promotes the beer as a revered regional speciality.

Opening my Grand Cru, I rediscovered a deep chestnut brown beer with a reddish tinge, and a light beige head that left soft lace on the glass. The aroma was immediately familiar and distinctive – sharp with orange citrus and balsamic qualities, and a hint of minerals and iron, the latter leading on to a suggestion of blood.

The palate was also intense and notably sour with a complex acidity layering very full fruity and chocolate notes. A refreshing swallow left a lightly acidic trace, with funky woody notes, more chocolate and a perfumed touch reminiscent of lemon and honey permeating a long finish.

The beer remains an enduring classic, and one I personally delight in, though it’s unarguably an acquired taste. When I presented it at a recent private beer tasting for a corporate client, it divided the room. Like lambic, it seems the keenest conventional beer drinkers are often the most challenged, while those who believe they don’t like beer can find it refreshing and beguiling.

Leave a Reply