They say…

Best beer and travel writing award 2015, 2011 -- British Guild of Beer Writers Awards

Accredited Beer Sommelier

Writer of "Probably the best book about beer in London" - Londonist

"A necessity if you're a beer geek travelling to London town" - Beer Advocate

"A joy to read" - Roger Protz

"Very authoritative" - Tim Webb.

"One of the top beer writers in the UK" - Mark Dredge.

"A beer guru" - Popbitch.

|

Lamb Tavern, London EC3 London’s Best Beer, Pubs and Bars updates

Central London: City

Traditional pub, bar (Young’s) Regional heritage pub

10 Leadenhall Market EC3V 1LR

T 020 7626 2454 w www.lambtavernleadenhall.com f Lamb-Tavern, Old-Toms-Bar tw thelambtavern, OldTomsBar

Open 1100-2300 (Closed Sat-Sun). Children welcome until early evening.

Cask beer 4 + 3 (Wells & Young’s, local guests), Other beer 3 keg, 10 bottles (Camden Town, Meantime, Wells & Young’s), Also 17 wines.

Food Upmarket pub grub, cheese and meat boards, Outdoor Tables on market, Wifi.

Seaonal events, functions, occasional major big screen sport.

The impressive looking Lamb Tavern, in the unique and beautiful setting of Leadenhall Market, is both a City institution and a tourist attraction, pulling in power lunchers from local financial firms and guidebook clutching heritage seekers. As a tenanted Young’s pub in longstanding family hands, it boasts more character than some. The extravagant exterior in deep red and cream is of a piece with the surrounding market (see below), while one of the most striking features inside is a tiled panel by the right hand door, dated 1889, depicting Christopher Wren explaining his plans for the nearby Monument.

Old Toms Bar, Lamb Tavern, London EC3 The main bar is small and largely given to vertical drinking in traditional dark wood surrounds, offering Young’s Bitter, London Gold and Ordinary on cask and a guest that sometimes comes from the East London brewery. The mezzanine, a comfortably jumbled space with more seating, is a more recent addition. A limited bar menu of lunchtime rolls and simple cooked meals is supplemented by an upstairs restaurant with an offer firmly targeted at Financial Times readers.

The surprisingly extensive green and cream-tiled vaulted cellar is under the same management but has recently been relaunched as a self-proclaimed craft beer bar under the name Old Tom’s. The range turns out to be rather more limited than that phrase might imply, concentrating on better known London brewers. Redemption and Sambrook’s are often on cask, two Meantime beers are on keg and there are further Meantime beers alongside Camden Town in the bottled fridges, with grazing plates of cheese and charcuterie if you wish.

Visitor note. Leadenhall Market began in the 14th century as a cheese and poultry market for non-Londoners, later becoming a general market. Old Tom’s Bar is named after a goose who in the 18th century somehow managed to evade slaughter and lived in the market to the ripe old age of 38. The current wrought iron and glass arcades date from an1881 rebuild by architect Horace Jones, who was inspired by Milan’s Galleria. Restored in 1991, it now houses specialist stalls and shops. In recent years it was the location for Diagon Alley in the Harry Potter films.

National Rail Cannon Street, Fenchurch Street, Liverpool Street Underground Monument / Bank DLR Bank Cycling LCN+ 10 11 15, links to NCN 4, CS7 Walking Jubilee Walkway, link to Jubilee Greenway, Thames Path

A Pilsner Urquell dray begins the long trek to Johannesburg… Pic: Pilsner Urquell I’m one of several writers who’ve complained in the past about the way in which the fanciful notions of marketing departments inform so much of the received wisdom on the history and heritage of brewing, and recently I’ve witnessed the process in operation at close quarters. It happened at the European Beer Bloggers Conference (EBBC) in Leeds, which enjoyed significant sponsorship from the US-South African conglomerate SABMiller, fronted by its premium Czech lager brand Pilsner Urquell. Urquell hosted the Saturday evening conference dinner in the wonderful surrounds of the old Corn Exchange, providing not only food and beer but some semi-serious lectures and demonstrations on the beer’s history and provenance. The problem was that some of the ‘history’ just didn’t add up.

As most people with at least a passing interest in the history of beer styles will tell you, Pilsner Urquell – Plzeňský Prazdroj in Czech – claims a highly significant slice of brewing heritage. Back in the 1840s, the brewery first defined the style of well-hopped pale golden lager that today sets the framework for the vast majority of the world’s beer production. The terms ‘pils’ and ‘pilsener’ originally derive from ‘Pilsen’, the German name of the brewery’s home city of Plzeň, some 85km west of Prague, but now appear on the labels of thousands of beers across the world, many of them only distant and degenerated derivatives of the original model.

Gateway to a new era of brewing: the landmark gate at the Plzeň brewery. Pic: Pilsner Urquell Now, the exact story of the origin of pilsner beer is unclear and disputed – see for example Czech-based US beer writer Evan Rail’s challenge to the account given in the Oxford Companion to Beer – though the legend that the golden lager came about by accident is now discredited. At the time, most beers were still dark, and cold fermentation was still a minority technique, but for some reason the 12 citizens of Plzeň who got together to build the brewery in 1839 decided to brew a pale beer using a cold fermenting “lager” yeast.

In those days Bohemia was part of Austria-Hungary. The German language was widely spoken and German culture and ideas were common currency, enjoying some prestige. Bavaria was then the principal centre of lager brewing, so it made sense to invite a Bavarian brewer, Josef Groll, to oversee the new brewery.

Paler beers were not unprecedented. Britain then led the field in pale malt production, using indirectly heated and coke fired kilns. It’s likely that the pale ales for which Britain became famous from the middle of the 18th century were notably light in colour, as some of the revivalist versions are today. According to brewing historian Martyn Cornell, in 1842, the same year Groll brewed his first batch in Plzeň, a Burton upon Trent brewer was promoting “East India Pale and Golden Ales”.

The year before, in the Austrian capital, Vienna, Anton Dreher had attempted to replicate the pale colour of the beers he’d seen on a British visit, ending up with an amber beer in a style known today as Vienna lager. Possibly Groll was influenced by Dreher, who had links with the Spaten brewery in the Bavarian capital, Munich.

The first Pilsner Urquell brewmaster, the Bavarian Josef Groll. Pic: Pilsner Urquell. Plzeň’s new brewery, like many at the time, was equipped with its own maltings where British ideas, if not British techonology, were used to achieve the optimum pale colour in the malt. It’s sometimes said that equipment was bought from Britain, but an 1883 history of the city quoted by Evan Rail speaks only of a kiln “equipped in the English manner,” presumably using indirect heat.

The beer brewed in Plzeň in 1842 was groundbreaking, placing the brewery at the cutting edge of innovation in the industry. 170 years later, Pilsner Urquell, as it is now known, markets itself, somewhat ironically, on its tradition and heritage, attempting to reclaim the somewhat debased term ‘pilsner’ by insisting it is the Ur-Quelle, the ‘original source’ of golden lager (the Czech term prazdroj means the same thing). Recently it has taken to describing itself as “the world’s first golden beer.”

Pilsner Urquell is now the Czech Republic’s largest brewery, claiming around 50% of the domestic market across its brand portfolio. But internationally it faces strong competition from another Czech heritage lager – Budweiser Budvar, otherwise known as Budějovice Budvar or Czechvar. Under the pro-Soviet regime of the1960s, Budvar and Urquell, then both products of nationalised industries, were picked as the brands most likely to raise hard currency in the export market, and both are still much better known across the world than any other Czech beers.

Set beside Budvar, Urquell today faces an image problem. The brewery was privatised following the political changes of 1989, and in 1999 it was bought by South African Breweries (SAB), which in turn merged in 2002 to form SABMiller. The new owners brought badly needed investment, but also introduced sweeping changes to the production process which were widely criticised for allegedly damaging the character of the beer. Influential established beer writers, who had known both beers from the days before the Velvet Revolution, presented Urquell as the corporate sellout, while lionising the much smaller Budvar for its continued resistance to privatisation and for holding its ground in the long-running trademark dispute with big US brewer Anheuser Busch.

Groll’s successor, the effusive Václav Berka, displays Pilsner Urquell’s basic ingredients at the European Beer Bloggers Conference in Leeds, 2012. Pic: Pilsner Urquell. So it’s not surprising to find Urquell on a charm offensive to win friends among the new generation of online opinion formers. The brewery has two strengths here. The first is effusive head brewer Václav Berka, one of those big personalities often encountered in the industry, bursting with enthusiasm for the beer he brews and oozing authenticity from every pore.

The second is the beer itself. Pilsner Urquell’s flagship 4.4% beer still tastes pretty good, particularly the unfiltered, unpasteurised version known in Czech as kvasnicový. Served by Václav himself at both EBBC events so far, complete with much ritualistic hammering of taps into wooden casks, this beer is sublime. Originally it was only available at the brewery and in a select handful of Czech pubs, with export markets receiving only the filtered and pasteurised version, but it’s gradually becoming more widely available, including to some specialist pubs in the UK.

Sadly these days no beer sells by its quality alone, particularly an international brand from a big brewery. Indeed the actual liquid itself is often a relatively minor part of the overall ‘brand proposition’. And Urquell seems to be generating ever more elaborate and more fanciful supporting narratives with which to surround the beer, riding roughshod over brewery history in the process.

In Leeds, we were briefed on aspects of this brand story. Amid lessons on correct pouring from Robert Kecskes, the current UK Pilsner Urquell Master Bartender (and although Robert was charming, I could write paragraphs about brands that attempt to create a mystique around the pouring process), and a talk on current production by Václav, we were treated to a monologue from ‘the Storyteller’, an actor with the sort of drama school-trained voice that can easily boom to the back row of the top tier at the Olivier and beyond.

The problem was that the story turned out to be a fairytale, presenting a romanticised and mythologised version of the beer’s history laced with pretty but unreliable details of the sort that send certain brewery historians into apoplexy. Thankfully the Brewed-By-Accident myth wasn’t retailed, but we were still told that Pilsner Urquell, the “world’s first golden beer”, is still brewed to the “same recipe” as Groll used in 1842, with malt from “nearby Moravia” and Žatec hops.

Pilsner Urquell UK Master Bartender 2011 Robert Kecskes with a traditional wooden barrel of the ‘Original source’, Leeds 2012. Pic: Pilsner Urquell. It should be obvious from what I’ve written above that Urquell’s claim to be the first golden beer is shaky to say the least, as it’s likely beers of this colour were around in Britain long before. And claims about recipes unchanged for many years, although regularly made about particular beers keen to exhibit their heritage credentials, deny the practical realities of commercial brewing.

The “nearby” Southern Moravian barley growing region is well over 200km from Plzeň and even Žatec is 70km away – with transport back then, it’s likely more local ingredients were used. Indeed Evan Rail quotes sources that record the first barley for the brewery’s own maltings was simply bought at the weekly market in Plzeň.

The methods have certainly changed, most recently when SABMiller took over and modernised the brewery. Traditional open wooden fermenters were replaced with closed steel cylindroconicals and the old wooden barrels used for lagering were also exchanged for modern tanks, inevitably impacting on the behaviour of the house yeast.

One of the key features of lager beer brewing is lagering itself, when the beer is left to mature in tanks at near-freezing temperatures following primary fermentation. This process derives from the style’s roots in the old Bavarian practice of storing beer over the summer months in cold caves (lagern means ‘to store’ in German). During lagering, the beer stabilises and various chemicals that might otherwise taste harsh and unpleasant are slowly broken down, giving a cleaner and better integrated flavour.

But lagering times often come under pressure when breweries modernise and rationalise. To a management accountant, all that beer slumbering for months in the lagering hall looks like so many wads of cash locked away in a safe when they should be out there circulating and generating profits.

At EBBC, I asked Václav Berka how long the current beer is lagered for. He replied, rather cagily, that the total brewing time is now five weeks – the same period, he claimed, as in Groll’s day. This may be true, but at some point in its history the beer was lagered for much longer. When beer writers Michael Jackson and Roger Protz visited Urquell independently in the 1990s, they were both quoted lagering times of 70 days, whereas now that period, taking account of brewing and fermentation, looks closer to three weeks.

But do such things matter? Assuming you agree with me that beer is worthy of being treated as seriously as other products of human endeavour, you may still say that surely this was a light hearted presentation, not an article from a serious reference book or journal. The problem is that, given the current environment in which beer is discussed, myths about beer history have a habit of passing into folk knowledge and being quoted as fact in other contexts. Sure enough, within a few days of the event, some elements of the “history” were being repeated uncritically by beer bloggers.

I commented on one such post on Phil Hardy’s Beersay blog – I’m not singling Phil out but his was the one I had the time to respond to when I spotted it. My comment, interestingly, sparked a response from Vanessa Hollidge at Urquell’s PR agency in the UK, Gabrielle Shaw Communications. Vanessa wrote in an email:

You are correct in stating that in the case of Pilsner Urquell production methods have been modernised to deal with modern demand, but we can confirm that the recipe and taste remain extremely unaltered [my italics] from the original brew. This is done through the use of parallel brewing methods, where quantities of hop wort is [sic] regularly fermented and matured the traditional way in wooden vats and barrels for quality control and our brewers constantly test and compare to remain faithful to the original.

Also as a cautionary measure Pilsner Urquell has invited groups of independent experts to the brewery to conduct a full test analysis. For example, The Research Institute of Brewing and Malting PLC [at the Brewing Institute in Prague] has tested Pilsner Urquell from 1897 until present day and provided confirmation to the brewery in 2008 that the average analytical parameters of Pilsner Urquell remained practically identical to the parameters recorded in 1897. Exhaustive taste testing within the brewery itself also means knowledge is passed on.

I wrote back to Vanessa saying I was pleased that Pilsner Urquell took quality control seriously, and was especially interested to hear about the parallel test brews. It’s also good to have an admission that production methods have been modernised, though this contradicts the assertion that the recipe has remained unchanged.

The claim that the taste is “extremely unaltered”, though, reaches further heights of absurdity. Beer is a perishable product – it’ll even taste different if left to stand in a glass for half an hour – and flavour is one of the most challenging sensory experiences to record in an objective way that will allow meaningful comparisons across time. Today we have a more detailed, but still incomplete, understanding of both the chemistry and sensory aspects of flavour, and tasting panels trained to map flavours using a rigorous methodology, but even this is not flawless, and nothing like it existed 50 years ago, let alone 170.

Vanessa later sent me a copy of the declaration from the Brewing Institute, which confirms that basic parameters such as the original gravity (the proportion of fermentable sugars in the unfermented wort), attenuation (the extent to which these sugars are converted to alcohol during fermentation) and alcohol content of samples from the past 15 years correspond to those measured by the Chemical Research Institute in Plzeň and the Chemical Laboratory in St Gallen in 1897. This is interesting in itself, but says nothing even about bitterness levels, let alone the overall flavour.

Pilsner Urquell today: still a pretty good beer. Pic: Pilsner Urquell. The most important point, however, is that Pilsner Urquell shouldn’t need to pretend that nothing important has changed over the best part of two centuries. Beer ingredients, methods and flavours change for perfectly good reasons, to compensate for inevitable changes in quality, composition and availability of raw materials over time, to take advantage of improved technologies and ingredients, and because brewers believe they can brew better beers by changing what they do. Slavish recreations of obsolete brewing methods are of great interest to historians and archaeologists, but there’s no reason they should have a place in a working commercial brewery. If Pilsner Urquell today wasn’t a better and more consistent beer than it was in 1842, 170 years of development would have been in vain.

Indeed in a later email, Vanessa told me more realistically that “so as far as we can control and influence, we think [the beer is] as similar as it could be while producing on a decent scale.” This is indeed the best that any contemporary brewery could be expected to do with a heritage brew. But it opens up a new area of debate, as to whether or not ingredients and methods have been changed simply to reduce costs and increase profits when this impacts negatively on the beer’s quality and character.

This is the allegation longstanding Urquell drinkers make about the changes introduced by SABMiller. I don’t trust my taste memory enough to say they are right, but the claims sound plausible, particularly as regards the standard pasteurised product. Unfiltered, unpasteurised Pilsner Urquell today tastes like an excellent beer to me, though perhaps it might be even better if lagered longer.

As a final thought, if Josef Groll and the citizens of Plzeň had decided to stick to established practices, they would not have taken the leap of faith necessary to produce a beer that changed the face of brewing. When drinking Pilsner Urquell today, let’s celebrate their courage, foresight and innovative spirit, not muddy their achievement with fairy tales.

European Beer Bloggers Conference 2012

Top Tastings 2012 (Siberia)

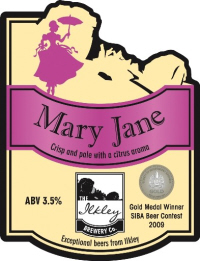

ABV: 3.5% and 5.9%

Origin: Ilkley, Bradford, England

Website: www.ilkleybrewery.co.uk

Ilkley Mary Jane It’s a generational thing, not a Yorkshire thing. When I heard that the Ilkley brewery’s flagship cask ale goes by the name of Mary Jane, it made perfect sense. The name is a reference to a folk song sung to a thumping hymn tune that was not only regarded as Yorkshire’s unofficial national anthem but also once formed part of the repertoire of every English schoolchild, even in Lancashire. The song’s narrator is concerned for the health of an unnamed interlocutor who has apparently been courting someone called Mary Jane in the inhospitable surroundings of Ilkley Moor without wearing a hat:

Tha’s been a cooartin’ Mary Jane

On Ilkla Moor baht ’at…

Tha’s bahn’ to catch thy deeath o` cowd.

However, according to youthful Ilkley brewer, Luke Raven, these days fewer and fewer people recognise the reference. The brewery is in Ilkley itself, an historic spa town nestling in Wharfedale close to some beautiful countryside, not only the Moor to the south but the Yorkshire Dales national park to the north. Although opened in 2009, it’s claimed the name of a previous Ilkley Brewery, operating between 1873-1923 and once one of the biggest in Yorkshire. The new brewery deliberately combines tradition and innovation, producing beers that are admired both by established cask ale fans and “craft beer” drinkers seeking more adventurous flavours, many of whom are doubtless entirely ignorant of Mary Jane and her rustic trysts with bareheaded admirers.

Arriving in Leeds before the European Beer Bloggers Conference (EBBC), I took a Twitter follower’s suggestion and went to lunch at Veritas in Great George Street, which turned out to be an inviting and friendly combination of a beer bar, tearoom and deli in the care of small pubco Market Town Taverns. A cask session beer with a resonant name from a relatively local brewery seemed a good choice to start my sojourn in Yorkshire, so I ordered a Mary Jane.

The beer is a crisp golden ale of the type that’s now become so ubiquitous and popular on the British cask scene, but with more hops than is typical, including large quantities of US variety Amarillo. Pulled northern-style through a sparkler and in immaculate condition, this very pale straw coloured beer had a close and foamy white head and a lovely floral and citric aroma with a firm cereal note beneath.

Some people say the beer is unbalanced but I found it integrated well on the drying palate, with plenty of spicy and rooty bitter flavours offset by cheerfully refreshing citrus and a sweet fruit hint. There was plenty of soft malty body in the drying finish which soon developed crackly and earthy pepper hop flavours without becoming overpowering. Overall it’s an impressive beer for its notably low strength.

Ilkley Siberia Rhubarb Saison Ilkley then popped up at the conference, with their Lotus IPA featuring in a tasting session, but Luke was also sharing bottles of a recent special, Siberia, a ‘rhubarb saison’ created with beer writer Melissa Cole. The designation ‘saison’ is now used very loosely in the English speaking brewing world, appearing on beers with only a remote connection to Belgian classics like Saison Dupont to connote a vaguely rustic funkiness, and its use here is equally questionable, although it does use a saison yeast. But aside from that, it’s a thoroughly delightful beer.

The rhubarb is particularly appropriate as it’s something of a local delicacy – a little way south of Ilkley, on the other side of Leeds, is the ‘rhubarb triangle’ producing Yorkshire forced rhubarb, which now enjoys EU Protected Designation of Origin status. But though this tart dessert plant now seems as Yorkshire as pudding, it originated in Siberia, thus the name. The hops also evoke more distant climes – Slovenian Celeia, Czech Žatec, Australian Galaxy and New Zealand Pacific Hallertau.

So far Ilkley’s regular bottled beers have been filtered but Siberia has happily been bottle conditioned in saison style. It poured a lively, cloudy yellow with some white head. A definite slightly stinky yeast note with a faint hint of buttery diacetyl rose over light grains and a twist of lemon in the aroma. The lemon note persisted in the palate, but with an emerging dry hoppiness over the citric tang that developed quite a bitter punch without becoming overpowering. There were some funky and spicy notes and even a hint of clove.

A bitterish finish turned out to be rather clean and refreshing, with more citric flavours, a hint of exotic perfume and lingering hops. The rhubarb might not have been noticed if you didn’t know it was there, but it did add a dry tartness to this very distinctive and drinkable beer. Well worth looking out for.

Update, March 2013. I’ve subsequently tried Siberia in two different draught formats.

At the Great British Beer Festival in Autumn 2012, the cask version had a good white head and a tart, spicy and lightly flowery aroma with a touch of toffee and cream. A coriander-like note floated on a toffeeish complex palate with tart apple flavours and lots of spice. A smacky finish had chewy hops and a light nutty bitterness, making for a very pleasant and tasty beer.

A lively keykeg version sampled that same month at the Earl of Essex, London N1, was even better, yielding a very spicy aroma with obvious rhubarb notes alongside flowery malt. A lightly tangy palate was again very spicy with a note of tart astringency among soft wheaty cereal and fruit. The tartness persisted in the finish with drying hops, soft fruit and a hint of custard.

European Beer Bloggers Conference 2012

Birra del Borgo Equilibrista ABV: 10.9%

Origin: Borgorose, Latium, Italy

Website: www.birradelborgo.it

Even the most experienced beer taster ultimately comes up against subjective judgement and hazy guesses about brewers’ intentions when evaluating beers, particularly those that push the envelope of categories. Plenty of professionals struggle with lambics and the new wild beers inspired by them, and once as a table captain at a beer competition I had to manage a serious argument with some members of my team – including a rather good professional brewer – who felt Samuel Adams Triple Bock should be disqualified as it wasn’t a beer.

I mention this as I’m not sure where I should stand on this particular, rather extraordinary, beer, which I tasted at an international beer tasting at the European Beer Bloggers Conference in Leeds. It originates from Birra del Borgo, one of the most widely acclaimed of the new breed of small Italian craft brewers.

Founded by former biochemist and home brewer Leonardo Di Vincenzo in 2005, the brewery now operates on two sites in the small village of Borgorese. Its best known brand is ReAle, one of the earlier European takes on a modern American pale ale, but it makes a wide range of seasonals and specials often incorporating unusual techniques and ingredients.

Equilibrista is one such, classified by the brewery as bizzarre and sperimentale in style, and brewed in small quantities once a year. It’s an attempt at a beer-wine hybrid, aiming to achieve the ‘equilibrium’ of the name. A conventional hopped barley malt wort is added to the must of Sangiovese grapes, the latter making up 39% of the mixture, and fermented with wine yeast.

The beer is then treated according to the methode traditionelle used for Champagne – refermented in the bottle with Champagne yeast over the course of a year, with bottles stored upside down and turned by hand to encourage the sediment to settle on the cork, which is then rapidly removed and replaced in a process called dégorgement, at which point another dose of concentrated must provokes a renewed sparkle.

There are other ‘Champagne’ beers, of which perhaps the best known is Bosteels DeuS, but this is something rather different that doesn’t attempt to imitate Champagne as such. My sample, from the 2011 vintage, poured a rich pinkish amber colour with a fizzy, slightly pink-tinged head. The aroma was decidedly winy, but still with subtle notes of hops besides the fruit, and a slight but definite trace of lambic-like wild yeast.

The palate was rather sweet at first, reminding me more of those luscious Italian sparklers like Asti Spumante than the more prestigious and drier French variety. There was plenty of grapey fruit, but the beer rapidly dried, becoming quite tart, with a complex and definitely sour lemon juice note and some spicy, grapy complexity.

Tannins from grapeskins – a very unusual note in a beer – were a feature on a lightly citric, subtly fruity finish with a hint of vanilla. And that light sourness persisted – not overwhelming, and actually making quite a harmonised contribution to the overall complexity. I noted a very rewarding taste experience, with the funky sourish notes a pleasant surprise in what was already a highly unusual beer.

Then a few days later, another beer expert – a highly experienced taster and beer judge – told me that the sourness was unintentional. Presumably at some point in the complex process, some bug or other [corrected from “a wild yeast” — see comments below] sneaked in unwanted and did its acidic stuff. I haven’t been able to verify this, but I do recall there was no mention of wild yeast on the label, there’s certainly no mention of it on the brewery website, and while some online reviews refer to the sourness (and ratebeer even classifies it as a ‘Sour Ale/Wild Ale’), others do not. And Champagne shouldn’t be sour, so why should a drink that’s trying to strike a balance between beer and bubbly?

So was I taken for a mug in being caught rhapsodising over a bad beer with a serious technical fault, of the sort that I’d normally pour straight down the sink? Was I seduced by the reputation of the brewer, by the trendy status of Italian craft beer, by the enigmatic label and the stylish designer bottle with its cork and capsule?

I don’t think so. If this was an accident, it was a happy one, at least to my taste. The sourness wasn’t overbearing, and worked well against the rich, deep fruity tones of the wine must and the relatively light hopping. There are precedents for sour beers made with grapes – such as the much admired grape lambic Vigneronne from Brussels’ Cantillon brewery. While it would be interesting to taste Equilibrista as intended, a deliberately funky version might also have a future.

As to whether a drink made with wine yeasts and a large quantity of grape sugar in its primary fermentation qualifies as a beer or not, that’s an argument for another day.

Top Tastings 2012 (Kroužkovaný ležák 12°)

ABV: 5% and 4.7%

Origin: České Budějovice, Jihočeský kraj, Czech Republic

Website: www.budejovickybudvar.cz

Budějovický Budvar kroužkovaný ležák 12° straight from the conditioning tank — note security device on glass. These are the unfiltered, unpasteurised draught versions of Budvar’s flagship golden lager (labelled Budvar Czech Imported Lager in the UK, Czechvar Premium Czech Lager in North America and Světlý ležák in Czech), and the dark beer simply labelled Dark Lager in English. The unpasteurised pale beer is more widely available than it used to be in the Czech Republic, and occasionally pops up at beer festivals and special events elsewhere. The unfiltered version of the dark lager is very rarely seen, but I was lucky enough to sample both in the lagering hall of the brewery itself, drawn straight from a tank.

It was cold in there – the temperature is kept at around 2°C, a few degrees below the ideal drinking temperature – but the qualities of the beer shone through. The first beer, made with Moravian pale malt, poured a cloudy gold with a thick, rich head leaving plenty of lace on the glass. The hops showed through much more clearly than on filtered and pasteurised versions, with a typical Žatec spicy, grassy, lemony note.

A full palate had a comfortingly broad malt character but with a decent hop bite and fleeting lemon and spiced orange notes. A touch of perfumed orange in the finish reminded me of Cointreau, with a crackly bitterness building over more soft malt, and a very light fruity yeast touch.

The second beer was a very dark brown, nearly black, made with Munich, caramel and coloured malts alongside pale. A thick bubbly beige head gave forth a solid dark malt aroma with chocolate and lightly roasted notes. The palate was deliciously rich and soft, with lots of fine chocolate and well matched bittering tones both from hops and roast, softened by subtle raisin fruit.

The grassiness of Žatec hops came to the fore in quite a bracing finish, still with a satisfying chocolate note and gorgeously fresh softness. Both beers are very special in this form but the dark was a real treat.

Read more about my Budvar visit.

The Budvar knights — saying No makes them what they are. In the early 1990s, as Czech brewing faced the new challenges and opportunities of the return of the free market, the trademark dispute between the USA’s biggest brewer Anheuser-Busch (AB) and South Bohemian brewery Budějovický (Budweiser) Budvar entered a new phase. The dispute, which had been running on and off for almost a century, centred on AB’s best-selling Budweiser brand and its attempts to stop Budvar using that same brand name on its own beer, even though the name derived from the Czech brewery’s home city.

In a rather misguided effort to drum up support in the UK, AB approached the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA), putting its case to several influential members including veteran beer writer and campaigner Roger Protz and CAMRA company secretary Iain Dobson. After the meeting, the CAMRA representatives were astonished to read a press release from AB claiming the organisation supported its case – completely the opposite of the impression they’d intended to give. Hastily, CAMRA put out its own corrective statement, and the ripples of the incident even reached to Prague Castle, with a copy of the statement faxed to dissident playwright turned president Václav Havel in support of an official government response. All in all it was something of a PR disaster for AB and heads, apparently, rolled.

The incident illustrates several extraordinary things about Budvar. First there’s that still unresolved trademark dispute, which has long since gone beyond the merely commercial and taken on national and international significance, widely interpreted in terms of a David versus Goliath parable that illustrates all that’s beastly about big industrial brewing. Then there’s the close links between Budvar and British beer campaigners, which go back a long way, despite the fact that the filtered, pasteurised and kegged products the Czech brewer exports to the UK are a long way from the approved definition of real ale.

The other thing most people with more than a passing interest know about Budvar is that, over two decades after the ending of the command economy in what was then Czechoslovakia, it remains a state-owned enterprise. This is despite numerous threats of privatisation down the years from pro-free market politicians, the most recent one fought off earlier this year. Privatisation and the trademark dispute are not unconnected. The latter would likely deter any commercial buyer other than AB’s successor AB InBev – now the biggest brewer in the world as well as in the USA – and the loss of the Budweiser brands to a foreign interest would be the near-inevitable outcome.

Budějovický Budvar brewery, České Budějovice, Jihočeský kraj, Czech Republic This unique social and political background added to my own interest when I was invited on a free trip to the brewery in České Budějovice in April 2012, part of my prize for winning a Budvar-sponsored award. I had some interesting travelling companions too – including longstanding brewery supporter Roger Protz himself, and Budvar UK’s veteran head of PR, Denis Cox, who has been associated with the beer since the days when pro-Soviet Communist Gustáv Husák ruled in Prague.

Visiting the brewery, and meeting its staff, it’s immediately striking how that social and political background is part of Budvar’s lived identity. Since 2005, the extensive site in an industrial suburb to the north of the city centre has boasted a glitzy, glass walled visitor centre that includes an extensive walk-through AV presentation on the history of the brewery.

Once you get past the Disneyfied depiction of Otakar II, the 13th century Přemysl king who founded the city, improbably quaffing golden beer from modern glassware, you’re plunged into the detail of the trademark dispute from its first rumblings in 1907. The climax of the presentation is a 20-minute parody spy thriller, lavishly shot in 3D, in which a secret agent hired by wicked men in expensive suits to collect evidence against Budvar ends up coming over to the Bohemian side.

And just in case you miss the point, a new domestic poster campaign features cartoon fantasy Slavic knights (above left), their armour collaged from various elements of brewery and city history, defending Budvar’s honour and reputation. “Saying No makes us what we are,” run the slogans. “No to selling our own name…No to moving production from České Budějovice…No to reducing the 90-day lagering period.”

There’s a subtext here identifying brand and nation. Despite its fame abroad, Budvar is not a huge seller at home, even in its own region. It’s currently third in the league table of Czech breweries, commanding only 6% of a domestic market dominated by Pilsner Urquell (Plzeňský Prazdroj) – but Urquell is owned by the US-South African group SAB-Miller which has notoriously streamlined traditional production techniques. SAB-Miller is linked to MolsonCoors which in April bought the second biggest Czech brewer, Staropramen, previously part of AB InBev. Heineken, meanwhile, owns the smaller Krušovice brewery. Budvar’s patriotic positioning is nothing new, as Czech nationalism played a role in the brewery’s foundation.

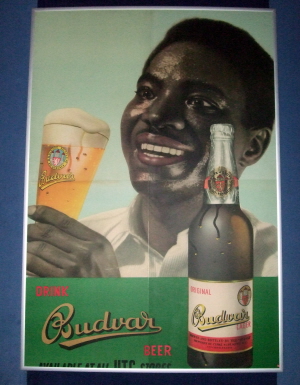

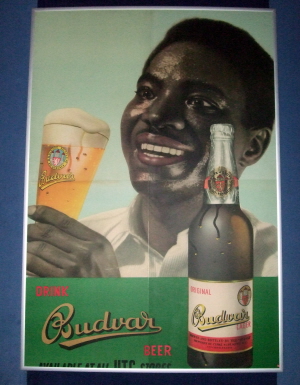

Past Budvar advertising on display at the visitor centre, though with no indication of what territory it was used in. Though many of AB’s arguments over the years have been spurious, the US group has the shred of a case in being able to claim that it was using the name Budweiser before Budvar was. To understand the history, you need to know that the Czech lands were once part of Austria-Hungary, and until some rather unpleasant episodes of ethnic cleansing in the immediate aftermath of World War II, had a significant German speaking population. German was once the official language, and most place names have both Czech and German forms.

The biggest markets for Bohemian products were German-speaking so unsurprisingly German was favoured in commerce too. At the end of the 19th century the population of České Budějovice was more-or-less half German and half Czech, with Germans more predominant among privileged social groups. In German the city is known as Budweis, and the term ‘Budweiser’ is simply a regular adjective meaning someone or something from Budweis, so any beer brewed there could lay claim to it.

From 1385 citizens had the exclusive right to brew within the radius of a ‘mile’ from the city – actually around 10km – and from the end of the 15th century domestic brewing was gradually supplanted by a municipal brewery which at the end of the 18th century came under the collective control of the citizens. This ‘Burgher’s brewery’, also known as Budweiser Bürgerbräu or Budějovický měšťanský pivovar, was the first to market Budweiser beer widely as a brand – a golden lager that challenged another famous geographically designated Bohemian beer, Pilsner, from the city of Plzeň (Pilsen in German).

Such was Budweiser’s success and fame that in 1876 Adolphus Busch, one of a number of German-American brewing entrepreneurs who were to transform the beer market in the United States, introduced a beer named Budweiser at his Anheuser-Busch brewery in St Louis, Missouri. Positioning this beer as a premium brand, and claiming it was brewed using authentic Bohemian methods, AB staunchly protected its trademark, pursuing other US brewers who used the Budweiser name.

As people of German origin secured their dominance of US brewing, back in Bohemia German speakers increasingly found their social supremacy challenged. Industrialisation in towns like České Budějovice shifted the ethnic balance as the new labouring classes were largely made up of Czech-speaking people displaced from rural areas, boosting the potential for Czech-run businesses.

In 1895 a group of Czechs led by August Zátka founded a joint stock brewing company, originally known as the Český akciový pivovar (‘Bohemian joint stock brewery’), to challenge the German-dominated Bürgerbräu. Logically enough it also used the term ‘Budweiser’ to identify its beers, though in 1930 it registered the brand Budvar, one of those Orwellian contractions popular at the time, comprising the first syllable of the city’s name in both languages, and the last syllable of the Czech word pivovar meaning ‘brewery’.

Budvar crossed swords with AB when it started to export to the US, with AB making much of the fact that its own use of the term ‘Budweiser’ as a brand predated Budvar’s by almost 20 years. In 1911 the Bohemian brewer voluntarily waived its right to use the term Budweiser in the US in return for compensation. The breakup of Austria-Hungary and the creation of Czechoslovakia as an independent state following World War I meant the loss of a large and favourable market for Czech breweries, encouraging further efforts in more distant markets, and the dispute inevitably flared again in 1937. Two years later both Budvar and Bürgerbräu, under pressure from the US courts, agreed to avoid the term Budweiser in the USA.

A few months later the outbreak of World War II put an end to exports to anywhere but Germany. A Nazi-approved management ran the brewery from 1942, and on liberation in 1945 it was shut down. It shortly reopened as a nationalised industry under the post-war coalition government. From 1948, under the pro-Soviet communist regime, Budvar became part of a regional group but since this concentrated only on serving the domestic market and other parts of the Eastern Bloc like the German Democratic Republic, the AB issue fell quiet.

Then in 1966, the Czechoslovak government decided to increase its hard currency reserves with a concerted programme of exports to the West. Two breweries were chosen to participate – unsurprisingly given their famous names, these were Budweiser Budvar and Pilsner Urquell, and the former was reconstituted as a separate entity again.

Three variants of Budvar brands necessited by the trademark dispute with Anheuser Busch. Note the strong common visual identify, first developed in 1932. The current international fame of both brands owes much to this bureaucratic decision of nearly half a century ago, ensuring they were already familiar to international audiences as the modern beer consumer movement emerged in the 1970s and 1980s. By using the brand Czechvar in North America, and hiding behind initials in the label details, Budvar got around the pre-war agreement with AB, but as that brewery too began to look to wider export markets, court cases followed in every country of the world where both brands aspired to have a presence.

In 1989 Husák’s government toppled alongside many others in the Warsaw Pact in the movement the Germans call die Wende. Czechs call it the sametová revoluce, the ‘velvet revolution’, and it was followed three years later by the ‘velvet divorce’ when the Czech and Slovak Republics became independent entities. Inevitably the changes heralded the return of the capitalist market and most previously state owned enterprises were ultimately privatised. Budvar, however, clung on in the public sector, and also flourished. As an exporting brewery it had emerged from the Cold War era in comparatively good shape, and under particularly skilful management it expanded still further, building on its international reputation to triple sales over a handful of years

But everywhere Budvar went, AB challenged it. A significant victory followed the Czech Republic’s entry into the European Union in 2004, when Budvar won the right to use the term Budweiser throughout the EU, obtaining Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) status in 2005. AB’s own application to use the term across the EU was rebuffed, with the result that while, for example, in the UK both breweries call their product Budweiser, in Germany only beers from České Budějovice are permitted to carry that label. Elsewhere AB has been more successful – in parts of the Far East, Budvar can use the Czech adjective Budějovický but not Budweiser.

The city’s other brewer has had rather more mixed fortunes – after decades of underinvestment prior to 1989, Budějovický měšťanský was privatised in the 1990s and despite some attempts at the export market, it has remained a small, local producer. Last year, in a complicated and rather dodgy deal, the business was split in two – one company owning the brewing assets, the other all the brands relating to the Budweiser name. The latter company was immediately sold to AB InBev, while the former ‘burghers’ brewery’ itself now makes beer exclusively under the Samson brand. This is the brewery that said Yes to selling its own name.

Budějovický Budvar managing director Jiří Boček explains his defiance of AB and the government at the brewery tap. Budvar’s managing director Jiří Boček says that the messy situation around the trademark is undoubtedly one reason his enterprise has avoided privatisation. He also points out that thanks to the unique legal status it was given back in the 1960s, divesting the brewery could prove a lengthy and difficult process. It’s effectively a semi-autonomous operational arm of the Ministry of Agriculture, governed by a board appointed by the minister. It would first have to be converted into a limited company, which would require an act of Parliament signed by the President, inviting a public debate and a challenge by opponents.

Undoubtedly, however, one of the reasons why Budvar has been able both to remain in public ownership and to thrive in such unusual circumstances is down to Jiří Boček himself. Appointed in 1991, he has proved a shrewd and determined steward, and, at 54, has found himself something of a national hero. I meet him in the pleasant surrounds of the brewery tap, its vaulted ceiling and heavy wooden furniture retaining a traditional beer hall ambience despite recent refurbishment. He’s a big man, not at all loud but confident and focused, with an obvious charm.

He’s also a brewer. His father was a senior Budvar brewer, and he worked there himself as a chemist and brewer in the 1980s before promotion to his current post. He’s not a management wonk or a money man, and doesn’t have any particular sympathy with those that are. He’s generous to his old adversaries at the former Anheuser-Busch, whom he regards as fellow brewers, and scathing of the accountancy and management-driven regime that now presides at AB InBev. He also thinks that to cave in to that company’s demands would spell disaster for Budvar. “To build a new brand is much more expensive than to protect your existing key brand,” he tells me.

Open lautering at Budějovický Budvar. Mr Boček’s reluctance to deal with AB InBev (all his staff refer to him this way, so I will too) was one of the accustations against him levelled earlier this year by his government adversaries. The current centre-right coalition is ideologically committed to privatisation, and identified Budvar’s managing director as one of the obstacles to pursuing that agenda. His nominal boss, agriculture minister Petr Bendl, set out to discredit him with the support of certain sections of the media, pointing to his alleged autocratic style and lack of financial controls. Bendl threatened to pack the Budvar board with pro-government appointees, and to strike a deal with AB InBev behind the brewery’s back.

But the campaign backfired on a government under pressure from several other quarters and quite likely to lose the next election to parties that have stated they would keep the brewery in public ownership. A South Bohemian MP has even promised a referendum on Budvar’s future that, according to opinion polls, would certainly reject privatisation. Mr Boček acquitted himself well, winning public sympathy with persuasive appearances on television. As a result all future privatisations have been put on hold – not only for Budvar but for other remaining public undertakings like Czech Railways and Prague Airport.

The brewhouse at Budějovický Budvar To top it all, Budvar has just announced some excellent annual results, growing domestic sales by 3.4% and exports by 7.7%, a performance significantly better than the industry average, and increasing its surplus by 9.2%. As a public body it’s not in the business of making profits so surpluses are largely reinvested, but Mr Boček points out that like other breweries it pays beer duty and VAT, and also donates voluntarily to social projects, mainly in its own region.

We’re shown around the brewery by former head brewer Josef Tolár, who is now officially retired, but like several others I’ve met in similar positions, clearly unable to stay away from the place. Though Budvar is in many respects a big modern brewery currently turning out some 1.5million hl a year, several aspects of the production process are striking in their adherence to traditional practices and old fashioned ideas about quality. You can’t help but wonder what view a private firm with shareholders to please would take on some of this, especially one that happened to be the world’s biggest brewer.

Our first stop is at a pair of big white tanks storing water drawn from the brewery’s own 300m-deep artesian wells. All the water used – both brewing liquor and cooling and cleaning water – now comes from this source. Next up is the handsome 1985 brewhouse with gleaming copper-clad vessels set in a big white-tiled hall. There are two interconnected mash tuns that work together to provide the traditional decoction mash, a lauter tun and a kettle. Despite the relative newness of the kit, the brewhouse still uses open lautering, with hot wort from the mash tuns gushing from a line of taps into a trough that drains into the lauter tun. Josef invites us to taste this comfortingly malty liquid, which has a rounded sweetness still recognisable in the final product.

Retired Budvar head brewer Josef Tolár with one of the key ingredients, whole leaf Žatec (Saaz) hops. Budvar once had its own maltings, but this has been replaced by an automated warehouse. Moravian pilsner malt is now the main malt used, with specially made coloured malt, also Moravian, for the dark beer. Another practice some brewers would regard as extravagant is the use of 100% Žatec (Saaz) whole leaf hops in the boil. Josef proffers a handful of the compressed leaves from a nearby sack – rubbed between the fingers, they have a beautifully fresh lemony scent. “You can drink beers made from whole hops all night,” he says. “Hop extract is too harsh. After half a litre the beer becomes undrinkable.”

The fermentation and conditioning vessels are all modern. The beer is fermented at a maximum temperature of 10°C in cylindroconicals, using a yeast culture that originally came from Bavaria in 1896. Examples of this are retained in the extensive yeast library at the Slovak Academy of Sciences in Bratislava, where it’s known simply as “Yeast strain number two”. The fermented beer then goes into big cylindrical tanks marshalled in the vast and chilly spaces of the lagering hall.

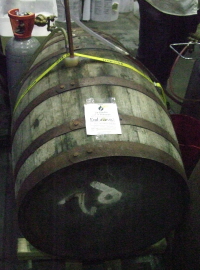

Wooden vessels were phased out in the late 1960s, though a few are still kept for show. With their great size and hefty locking systems, the old conditioning barrels look remarkably like some of the vessels used to mature lambic at the Boon brewery in Lembeek, and I’m reminded that some lambic brewers and blenders, such as De Cam, use oak barrels that formerly belonged to Pilsner Urquell.

Lagering tanks at Budějovický Budvar. There are no compromises on lagering periods. Budvar’s flagship beer, the standard 5% ABV světlý ležák 12°, spends 90 days in the tanks at a temperature of 2°C. Each tank holds around 3,700l and until a few years back there was capacity to mature 100,000hl at once. With sales growing, more capacity was needed. Many commercial brewers would have been tempted to increase throughput by slashing lagering times, but instead Budvar invested around Kč300m (£10m, €12m, $16m) in adding half as many tanks again. “We had good financial reserves,” says Josef.

The bottling line is highly automated, mainly with German equipment, and capable of getting through 40,000 bottles an hour. The snakes of full and empty bottles, and the robotic machines packing and lifting crates, are mesmerising to watch. During our visit, the line is on a run of Pardál, a more downmarket brand launched domestically in 2007 to compete with the likes of Urquell’s Gambrinus brand. One slight disappointment is the brewery’s preference for green glass for its custom embossed bottles, which affords the beer less protection. “It is for fashion and marketing,” says Josef. “Of course as a brewer I would prefer brown.”

Overall, it’s a glowing success story for a nationalised industry, enough to warm an old socialist’s heart – which I’m convinced is part of the reason Budvar is so appreciated in Britain. Many of the writers and campaigners that influenced CAMRA in its early years had left wing leanings, and wrestled with the contradiction of promoting a British industry dominated by the deeply Conservative ‘beerage’. The campaigners were generally not sympathetic to the one party state socialism of the Soviet Union and its allies, particularly after 1968 when Red Army tanks crushed the Czech liberalisation movement known as the Prague Spring. In the early 1970s Roger Protz was editor of the Trotskyist newspaper Socialist Worker, which carried the strapline “Neither Washington nor Moscow but international socialism” beneath its masthead. But in Czechoslovakia in the 1980s they discovered breweries making great beer without a profit motive. To a British socialist and beer fan, it must have seemed something of a dream come true.

“CAMRA always supported Budvar,” Roger tells me, “because it was a respectable beer.” During the 1980s it was imported in bulk through the Czech Ministry of Foreign Trade, and sent to Everards in Leicester for kegging. Back then, Denis Cox, now PR for Budvar UK, did a similar job for the Ministry, but there was no export department at the brewery itself or any direct communications with it. Roger himself first tracked the beer down to its source in the mid-1980s – he got a curious but friendly welcome and wasn’t allowed to visit the brewhouse. “Back then there was no domestic branding,” he recalls. “You went into a pub, asked for a pivo and took what you were given. You had to ask to find out if it was Budvar, Urquell or whatever.”

This was the decade when Britain’s own nationalised industries and public services created as part of the post-war Welfare State were being exposed to the ‘disciplines of the market’ under Thatcherist doctrine – in most cases to no obvious public benefit and with a notable amount of private profiteering. And while it was obvious that the Czech model wasn’t without problems and issues, including a chronic lack of investment, not to mention the viciously repressive regime that underpinned it, the rapacious capitalism that swept the former Eastern Bloc after 1989 would make the ‘fat cats’ that benefited from privatisation in Britain look modest and civilised in comparison.

But not at Budvar. It’s unclear how much the brewery’s status as a cause célèbre in Britain influenced its position at home. But it’s certainly helped the brand build credibility and a reputation for quality in its second biggest export market (the biggest is Germany, the third biggest Slovakia), and, through the international audience commanded by certain beer writers, in the rest of the English speaking world. The trademark story also appeals to those who instinctively side with the little man against the corporate bully.

A choice of Budvar beers on sale at the brewery tap. It’s also interesting to consider how the view of Budvar as a nationalised industry through British eyes might differ from the local view. For over 40 years, all Czech industries were nationalised, but even before that, local communal arrangements for certain industries, the legacy of mediaeval modes of production, persisted far longer in the German sphere of influence than in the UK. It’s somewhat ironic that České Budějovice’s communal brewery, Budějovický měšťanský, has become the privatised sellout, while Budvar, with its roots firmly in the late Victorian era of entrepreneurial capitalism, is now the people’s champion.

That’s not to say Budvar doesn’t still make, in Roger Protz’s words, “respectable beer”. The flagship golden lager is marvellously easy going with a rich cracker-like malt, subtly balanced with hops, and particularly delicious in its unfiltered, unpasteurised kroužkovaný form. Easier drinking still is the underrated výčepní (4%), in the lower alcohol style known as desitka after its original gravity of 10° on the old Czech scale. More recently introduced are a rather decent dark, an alcohol-free beer and the liqueur-tinged strong lager Bud Premier Select (7.6%), originally aimed at the Russian market. The previously mentioned Pardál beers use hop extract rather than whole hops, selling at a cheaper price with their own very distinct branding.

But then Budvar competes in a marketplace where standards, despite the turmoil of the past quarter century, remain notably high. SAB-Miller’s rationalisation programme may have been ruthless, but even Pilsner Urquell, still regarded here as a premium brand, can provide a decent glassful, with a notably hoppy bite that might appeal more to contemporary tastes than the milder, less focused Budvar. Some of the smaller historic regional and local breweries in the Czech Republic make even more noteworthy beer, but don’t boast Budvar’s dramatic backstory and remain largely unknown outside the country. And there are an increasing number of modern, internationally-minded micros and brewpubs too. Josef Tolár tells me he welcomes these new arrivals and their eclectic influences. “Czech brewing has imported many good ideas from the West,” he says, before adding with a shrug, “and all the bad ones.”

Budvar seems safe for now, but privately some brewery staff still feel insecure. Along with many other Czechs, they have little confidence in governments of any shade not to sell the brewery out. As opinion polls show, few people here trust their politicians, exhibiting the wry cynicism you might expect from those who’ve experienced the transition from Stalinist repression to the get-rich-quick graft of the free market.

And when all’s said and done, it would be a great shame to see the brewery and its traditions fall to the mercies of AB InBev and the like. Despite its relative youth in historical terms, Budvar boasts a fine sense of place, its roots as deep in the soil of České Budějovice as those artesian wells. The city, the regional capital of South Bohemia, sits on the meandering Vltava (Moldau in German), the country’s longest river, around 125km upstream of Prague and close to some of the Republic’s most beautiful countryside. The city centre clusters attractively on a small island formed by two arms of the river. Cobbled streets wind from the riverside to a fine and expansive square, where grotesque gargoyles sprouting from the old town hall overlook graceful pastel-shaded baroque mansions.

It’s a great place to enjoy a glass of unfiltered Budvar, perhaps in the historic Masné Krámy, the old meat market that has long been a showcase Budvar pub. AB may have won a few courtroom arguments, but the absurdity of this beer not being able to call itself after the place where it’s made surely flies in the face of natural justice. Long may Budweiser Budvar continue to say No to selling its own name.

See also Roger Protz, ‘Bounced Czech: the plot to do down Budvar‘

Update 5 July 2012: Following a process that went all the way up to the European courts, AB InBev has recently been told again by the UK courts that it has to share the Budweiser trademark with Budvar in the UK. Read more.

Beer picks

The opinions expressed above, and any errors, are my own, but for background information I’d like to thank Denis Cox, Roger Protz, Evan Rail and Petr Samec, and Denis and Budvar for arranging the trip.

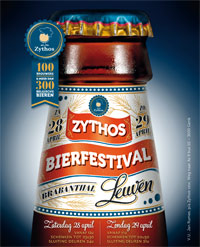

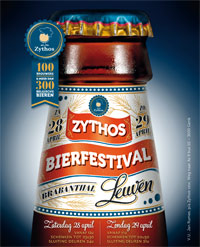

Zythos Bierfestival 2012, Brabanthal, Leuven, Vlaams-Brabant, België The most important beer festival in one of the world’s greatest beer countries just got bigger still. After several years packing out a smallish hall in the obscure town of Sint-Niklaas, the Zythos Bierfestival (ZBF) almost doubled in size in 2012 in its new home for at least the next four years, the Brabanthal in the historic brewing and university city of Leuven. The welcome additional space and extended choice should help ensure ZBF remains one of the world’s top beer events, and a fine showcase for the diverse and increasingly dynamic Belgian brewing scene.

This way for good beer... Unlike British beer festivals, ZBF allocates a small stand per brewery and this year the number of stands grew from 56 to 96. With a few sharers, 104 breweries and beer firms were represented, from tiny hobby outfits to multinationals, offering over 400 different craft and other specialist beers – with a waiting list of brewers who failed to secure a stand. Total attendance over the weekend of 28-29 April was up by 3,000 to 13,000, with plenty of room to grow still further over the coming years.

In contrast to Sint-Niklaas, a pleasant but ordinary small town with excellent transport links, Leuven has much to offer as a host city. 30km east of Brussels on the main road and rail routes east towards Liège and Köln, it was for many centuries an important brewing centre. Its most successful old-established brewery, Artois, has since bloated into global giant AB InBev and the city remains the international headquarters of the world’s biggest brewing group. But it’s long boasted an excellent independent brewpub, Domus, and in the past few years several small breweries have started up in the vicinity.

Besides its brewing links, Leuven is the provincial capital of Flemish Brabant and a fascinating and historic place in its own right, with some astonishing and important built heritage like the elaborate Gothic town hall and two peaceful mediaeval beguinages that enjoy World Heritage Site status. Significantly, it’s also home to the oldest and biggest university in the Low Countries, the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (Catholic University of Leuven, otherwise known as KU Leuven). A massive student population supports Belgium’s biggest collection of student pubs, occupying practically every ground floor of the long, narrow rectangle of the Oude Markt (Old Market Place) in the city centre. Needless to say, the university boasts a brewing faculty which has made a major contribution to the national industry.

The festival venue stands rather apart from all this. The Brabanthal is a giant box of an exhibition and convention centre next to a dual carriageway on the eastern edge of town. Regular attenders will have missed the convenience of the short stumble from Sint-Niklaas station to the Stadsfeestzaal almost opposite, but in mitigation a free shuttle bus operated every 15 minutes to and from Leuven station. I opted instead for a pleasant half-hour walk, plotting a route through the redeveloped former Philips factory site, the parkland and waterside of the Abdij van ‘t Park (Park Abbey) and along a track across fields. I confess to catching the bus back, though.

Zythos Bierfestival 2012 In common with the Stadsfeestzaal, the Brabanthal is a hanger-like space with a concrete floor and no natural light, but developed an adequate atmosphere when full of decorated brewery bars and crowds of eager drinkers, and the additional space was really welcome. Plentiful tables lined the walls around the bars, with much more standing and circulation room between them. Additionally the marginally more luxurious foyer offered more seating as well as hot and soft drinks in an extensive cafeteria, and spreading room for other stands, including a much expanded bottle shop stocked with unusual beers from small breweries. An outdoor food area enabled the enjoyment of that national staple, chips (fries) lathered with mayonnaise (or filled rolls and pitas or pizza slices) without the frying fumes detracting from the appreciation of beer aromas. There was also an extended outdoor smoking area – the festival has been smoke free for several years anyway and last year Belgian law caught up with it.

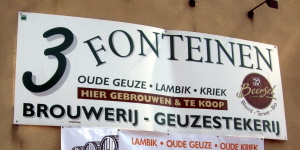

Armand Debelder presides at the 3 Fonteinen stand, Zythos Bierfestival 2012 One of the advantages of the brewery bars is that they are usually staffed by the breweries, giving drinkers the opportunity to meet the people behind the beers. Numerous brewers were in evidence at the festival – I spotted people from Brasserie de la Senne, Rulles, Alvinne and Tilquin. Lambic legend Armand Debelder was happily dispensing his own excellent beers at the 3 Fonteinen stand.

The whole spectrum of Belgian specialist brewing was represented. At one extreme, AB InBev put in an appearance for the first time I can remember, and quite right too given their local links. They were showcasing the Leffe abbey brands, including a new 5.5% beer, Nectar. At the other extreme were several new and often very small breweries, some run only as spare time hobbies. Danny, Dijkwaert, Donum Ignis, Gruut, Herberg, Hof ten Dormaal, Jessenhofke, Leite, Lupus, Maenhout, Nieuwhuys, Paenhuys, Pakhuis, Pirlot, Sint Canarus, Vlier, Wieze and Wilderen were among the less familiar names.

This profusion of newcomers, often showcasing distinctive and innovative beers, reflects the current healthy state of Belgian brewing. Given the reverence with which the country is regarded by beer connoisseurs internationally, and the uncritical view of most Belgian drinkers that their national beers are the best in the world, complacency is not unknown, but international awareness happily works both ways. 11million hl – more than half the country’s production – is now exported and Belgian brewers seem well attuned to changing tastes in the world market, which are increasingly feeding back into the home market too.

What is it about beer festivals and embarassing headgear? Pink elephants on parade at Zythos Bierfestival 2012. The happy result is that the country’s numerous surviving unique traditional styles seem secure, as attested by the recent arrival of a new geuze blender, Tilquin, though brewers no longer feel hidebound by them at the expense of experimentation. Unusual hybrids based on abbey beers and wheat beers, wood aged extreme stouts and pale ales with generous dosings of US hops were all on offer alongside classic lambics, tripels, saisons and spéciales belges. And with a 15cl glass of any beer available for a standard €1.40 token, there were plenty of bargains to be had at the rarified end of the market.

'Thou shalt enjoy'. The 11th commandment being obeyed at Zythos Bierfestival 2012. Alongside the Great American and Great British Beer Festivals, the Zythos Bierfestival is arguably one of the world’s top three events for serious beer lovers, reflected in the increasingly international attendance. A rainbow of English accents could be heard across the hall, and there were plenty of Scandinavians and Italians in evidence as well as Belgians and Dutch. The new venue and the attractions of the host city make it even more of a must-visit than ever, so make a note in your diary now for 27-28 April 2013.

Zythos Bierfestival 2012: festival glasses and ballot papers waiting to be filled. Insider tip. Admission is free, but if you’re a member of an EBCU (European Beer Consumer Union) affiliated organisation, you can also claim two free tokens (jetons) at the Zythos stand by showing your membership card. If you’re a member of more than one EBCU organisation, you’ll get two tokens for each membership. I can’t help feeling a little greedy every year for claiming six tokens with a flash of my CAMRA, PINT and Zythos cards.

On a personal note, Leuven is also the place where I underwent a major beer epiphany, almost exactly 20 years before, when my then partner, who was on a six month placement at KU Leuven, introduced me to Hoegaarden at the Oase, one of those many student bars on the Oude Markt. A few weeks later we bought a copy of Michael Jackson’s The Great Beers of Belgium between us and I never looked back. I found the Oase again the other day, though it was too early in the day for it to be open, but I’m glad to report that the Domus brewpub, another of our favourite haunts back then, is still going strong, and brewing again after a challenging period.

See also Zythos Bierfestival 2010.

Beer picks

Zythos Bierfestival 2012

ABV: 6.5%

Origin: Oudenaarde, Oost-Vlaanderen, Vlaanderen

Website: www.seef.be

Roman / Antwerpse Brouw Compagnie Seef Bier The consolidation and transformation of the brewing industry and the beer market in the 20th century swept away numerous local and regional beer styles, with beers once ubiquitous in their own territories rapidly declining and almost being wiped from memory. Porter is perhaps the best known example, but there are more, and some are only now being rediscovered as the growing interest in specialist and craft beer drives a corresponding interest in brewing history.

One such rediscovered style is ‘seefbier’, which for over a century before World War II was the signature beer style of the city of Antwerpen and its surroundings. It’s mentioned by several Flemish authors, and in folk poems and songs. According to Domien Sleeckx, writing in 1863, seef was “a white beer [‘wit bier’]…that foamed like Champagne, went to the head like port, and cost 10¢ a litre” (my translation). Lode Baekelmans, in 1904, made a similarly effervescent comparison in dubbing it “poor man’s Champagne”. It gave its name, which most likely derives from Latin sapa or Dutch sap, meaning juice or sap, to a district of the city, the Seefhoek to the north of the city centre. Incidentally, it’s not pronounced to rhyme with ‘beef’ as it looks to English speakers — try saying ‘safe’ in a Yorkshire accent and you’ll get closer.

Yet seefbier completely vanished. Today we think of the Belgian pale ale, De Koninck, as the signal Antwerpenaar beer – a style developed to compete with the seemingly unstoppable postwar popularity of golden lager, the latter now of course outstripping in volume all other beers in Antwerpen as it does throughout Belgium.

But seefbier has returned from the dead. Industry figure Johan Van Dyck, the marketing director at Duvel-Moortgat, became intrigued by the style a few years back and set about researching its elusive history. Seefbier brewers tended to keep their recipes secret, but Johan finally tracked down a brewer’s handwritten notes, which he analysed with Freddy Delvaux, brewing scientist at KU Leuven, and his son Filip, who had worked with Dogfish Head on their attempt at recreating an ancient Egyptian beer.

Previously, that description of seef as a ‘witbier’ or white beer had misled people into assuming it was a spiced wheat beer in the Brabant style typified by Hoegaarden, itself a revival of a temporarily extinct local speciality. But the research indicated a beer quite unlike any contemporary example, made from a mixed grist bill including oats and buckwheat as well as barley malt and wheat. The ‘wit’ description turned out simply to indicate a cloudy beer that was lighter in colour than most of its contemporaries.

Over several test brews, Johan and Filip evolved a new version of seef using the four grains, Belgian hops and an historic yeast strain not much removed genetically from a baker’s yeast. Johan set up his own beer firm, the Antwerpse Brouw Compagnie, with the initial aim of marketing the revived beer. It would have been a nice idea to brew it at De Koninck, but this proved impractical, so in December 2011 the first commercial brew of seefbier in many decades emerged from the mash tun at small family brewery Roman in Oudenaarde, and was finally launched to the public in March 2012.

I found it at the Zythos Bierfestival, bottle conditioned and poured from the bottle. It emerged a cloudy deep yellow with a smooth white head. A lightly spicy aroma had notes of ginger, clove and lemonade citrus. A soft and refreshing but very interesting palate yielded liquorice, custard, tangerine, fresh white bread, banana and vanilla cream.

The softness persisted into the finish, with a citrus peel tang, an unctuous smoothness perhaps from the oats, and a late note of hops. Overall it was a very cheerful and refreshing beer, and amazingly easy going for a relatively robust gravity. Distinctive and indeed different from any other beer I’ve tried, it’s a worthy resurrection which makes you wonder what other potential delights might be still be hidden in dusty and forgotten notebooks of long dead brewers.

Update 17 May 2012. After I posted this, Johan Van Dyck from Antwerpse Brouw Compagnie got in touch with some more information. The beer was officially launched on 9 March at Antwerpen town hall where the Mayor, Patrick Janssens, declared it the second official beer of the city, after De Koninck of course. The beer proved so popular that what was planned as seven months’ worth was sold out in a fortnight. Seef Bier was also submitted to the World Beer Cup in San Diego, California, earlier this month — “a bit over-courageous maybe,” reflects Johan — and ended up winning a gold medal in the Other Belgian-Style Ale category. In the process of researching the recipe, Johan unearthed numerous interesting old recipes that have inspired other ideas for new beers, but for the time being he is focusing on Seef.

I’m grateful to the following source for background information:

Johan ‘Wanne’ Madelijns (2012), ‘Johan Van Dyck wil oude bieren nieuw leven inblazen’ in De Zytholoog 36 (February 2012)

Zythos Bierfestival 2012

ABV: 9%

Origin: Baarle-Hertog, Antwerpen, Vlaanderen

Website: www.dedochtervandekorenaar.be

De Dochter van de Korenaar Peated Oak Aged Embrasse, Zythos Bierfestival, Leuven 2012 De Dochter van de Korenaar (‘the ear of corn’s daughter’, a poetic expression for beer) is a Belgian brewery, but only just. It was founded by a former home brewer, Ronald Mengerink, originally from Groningen in the northeast of the Netherlands, who lived for a time in France. When he finally went professional in 2007, Ronald located his brewery adjacent to his home in the intriguing location of Baarle-Hertog.

Connoisseurs of geopolitical eccentricity will be familiar with Baarle-Hertog, an enclave of the Belgian province of Antwerpen in the Dutch province of Noord-Brabant – or rather several enclaves totalling 7.5km2, some of which in themselves contain enclaves of the Netherlands. These enclaves are a legacy of 11th and 12th century land deals between the Dukes of Brabant, the Lords of Breda and the Counts of Holland that somehow managed to exert their influence beyond the foundation of the Kingdom of Belgium in 1831. The boundaries even bisect individual buildings and what life must have been like there before Schengen and the euro is hard to imagine.

De Dochter van de Korenaar is a small, artisanal setup and I have to confess my early experiences with its beers were not happy ones. But the quality has got more consistent in recent years and Ronald’s experimental approach has caught the interest of an increasingly globally aware young market of beer fans in both Belgium and the Netherlands.

Embrasse, first sold in 2008, is one of the brewery’s most highly rated beers, described as a cross between a strong, dark Trappist and an imperial stout, with a generous dose of hops more typical of the latter. It’s also been the basis of various oak matured special editions, including Peated Oak Aged (the English term is used), ripened for three months in oak barrels formerly filled with Connemara peated whiskey from the Cooley distillery in Ireland.

Last year Peated Oak Aged Embrasse was voted beer of the festival at the Zythos Bierfestival, and this year it was back, served from a suitably rugged looking barrel by handpump with the assistance of a CO2 cask breather.

The resulting beer was a very dark amber brown with a thick and bubbly head. A rich woody, leathery and meaty aroma had notes of black treacle as well as a definite whiff of peated malt whiskey. The thick chocolate palate was tingly with gentle carbonation, with oaky vanilla, tangy orange fruit, and lots of dark cakey malt, still with whiskey evident.

The woody vanillins became slightly more pronounced on a tangy finish, with more of that orange fruit, a pleasant sweetness and a roasty malt note that sat in the mouth, without the burnt quality of some beers in this style. A splendid beer that certainly redeemed my earlier disappointments.

Zythos Bierfestival 2012

ABV: 5.5%

Origin: Beersel, Vlaams-Brabant, Vlaanderen

Website: www.3fonteinen.be

Brouwerij en stekerij 3 Fonteinen, Beersel, Vlaams-Brabant, België The simplest way to make an acidic young lambic palatable is to bung sugar in it, and in the past this was probably the most common way of drinking lambic in its heartland in and around Brussels. Low gravity lambic, blended with a lighter beer that might not be spontaneously fermented, would have been dosed with brown sugar at the pub just before serving. The resulting drink, known as ‘faro’, was, like mild in England, an everyday refresher popular with manual workers from factories and farms.

These days faro is a minority style, usually made from standard strength lambic and pre-mixed with brown sugar, and perhaps some caramel, at the brewery or blender. The sweetening needs to be done shortly before serving, or the beer has to be pasteurised first, otherwise the sugar will prompt a refermentation and the beer will lose its sweetish, relatively still character.

I find the style fascinating, and 3 Fonteinen’s version is one of the rarest, usually only reliably on sale in Beersel itself, so I pounced on it when I spotted it at ZBF, served from a handpump. I wasn’t disappointed.