National Homebrew Competition, Bristol 2011

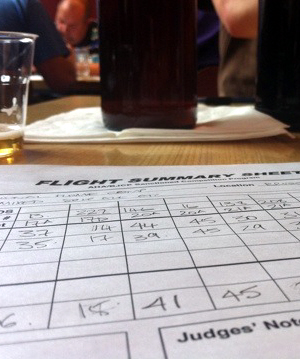

National Homebrew Competition 2011: the view from the judging sheet. Pic: Phil Lowry of beermerchants.com.

Home brewing still struggles with a bad reputation in the UK. Folk memories of Boots kits bought principally on the promise of only a few pence for a pint “just like you drink down the pub” but instead producing smelly, cloudy concoctions that remain the only alcoholic drinks left unfinished at the end of the party — such stereotypes die hard. When I told friends and colleagues I was going to judge a homebrew competition, their commiserations were delivered without a hint of irony.

This is unfair. There are many other fields of human endeavour where able and enthusiastic amateurs (and let’s not forget that for all its negative connotations the word derives from the Old French for ‘lover of something’) are accepted as capable of producing work that rivals and occasionally even exceeds in quality that of professionals — think of cookery or gardening, for example.

These same occupations enjoy healthy communication and interchange between amateur and professional spheres. In the USA and some other countries where a flourishing craft brewing scene has been built from scratch on the tabula rasa of a beer culture effaced by industrial brewing, the vast majority of commercial brewers have been recruited from among home brewers, and the ties remain close — witness the various ‘pro-am’ events and competitions on the other side of the Atlantic, and the commercial beers that began as prizewinning homebrew competition entries.

In Britain, where a tradition of commercial craft brewing persisted, the first generation of microbrewers was largely made up of professionals fleeing or made redundant from bigger breweries. Brewing on a domestic scale was once the norm, of course, but the ascendancy of the “common brewer” established a received wisdom that the “mysteries of the craft” were way beyond the scope of unpaid dabblers equipped with tea urns and plastic buckets, an assumption reinforced by most people’s experience with those 1970s Boots kits.

This assumption is becoming increasingly untenable. If doubts remain, they would quickly have been dispelled by random tastings of the entries at the UK National Homebrew Competition held in Bristol at the beginning of September 2011, where the quality the best homebrewers are capable of was obvious for all to taste. It was also significant that, besides homebrewing experts, the judging panel included some of Britain’s leading professional brewers — people of the calibre of Fuller’s John Keeling and Moor’s Justin Hawke — as well as beer writers and other industry figures, all of whom felt privileged to be asked, though it was purely on a voluntary basis and at their own travelling expense. Bristol Beer Factory, one of the UK’s more forward looking micros, offered invaluable practical assistance.

The crowd of hopeful entrants, helpful stewards and curious judges that gathered at the Tobacco Factory — the regenerated former Imperial Tobacco works in a now-trendy part of south Bristol — reflected the changing complexion of Britain’s developing beer scene. The home brewers were predominantly youthful and clearly alive to international beer culture — though almost exclusively male. Far from being an easy way of making pints for a pittance, brewing is for many of them a consuming pastime that involves serious commitment in terms of equipment and time.

This wasn’t about kits and malt extracts — pretty much all the beers in the competition were “full mash”, brewed from scratch with malt and hops just as in the commercial sector. In fact four entries were from professional brewers who made them at home, permissible under the rules of the competition which admitted any beer brewed on non-commercial equipment. The fact that full time brewers also spend their free time brewing is a demonstration of quite how much passion drives the industry.

I’ve judged at numerous commercial beer competitions but this was quite a different experience, and not just because we were asked to use the BJCP guidelines, of which more below. The bane of commercial competitions is not bad beer but boring beer — beer created under the pressure of marketing departments so obsessed with giving it the widest possible appeal they end up creating the lowest common denominator. Tasting a succession of technically flawless but bland beers with nothing distinctive to say for themselves can be a dispiriting experience.

Home brewers have no such commercial imperative — they brew to please themselves, and to satisfy their own curiosity. Yes, there were a scattering of misfires, “gushers” and bad beers in Bristol, perhaps a few more than you’d expect from the commercial sector (who are by no means immune to technical problems), but blandness certainly wasn’t an issue. The relatively high numbers of entries in the American pale, IPA and Belgian ale categories illustrates the point. The imagination on display was reflected in the final Best in Show winners — a delicious porter flavoured with vanilla, an American amber and a Bavarian-style wheat beer bursting with authentic spicy and fruity flavours.

Organiser and home brewer Ali Kocho-Williams says that, though there have been previous national competitions run by British home brewers’ club the Craft Brewing Association, this was almost certainly the biggest event of its kind yet organised in the UK, with 243 entries and 116 participants. And it was the first to use the BJCP guidelines. This is yet another example of how US craft beer culture, which was originally partly inspired by the beer consumer movement in Britain, is now returning the compliment by feeding the aspiration and imagination of young British brewers and beer connoisseurs.

The Beer Judge Certification Program was first set up in the 1980s by the American Homebrewers Association (AHA) and, although it is now adminstered by its own organisation, its accreditations and procedures remain in use for AHA competitions. The first BJCP exam in the UK was held in January this year and a number of official Beer Judge badges were proudly on display in Bristol.

“I got involved in the BJCP and qualified as a judge via the New York City Homebrewers Guild,” Ali told me. “I got excited and enthused, and came back to Bristol with a head full of ideas about developing a homebrew club. About a year ago I floated the idea within what was then a nascent Bristol Brewing Circle of organising a competition. This was originally going to be a regional event, but open to all. When the Craft Brewing Association announced that they weren’t going to run their competition this year, I was urged to turn ours into a national event. It all rather went from there.

“We decided to adopt the BJCP because it offered a much broader set of guidelines than those previously used in the UK. It also gave the beers a much better chance of being fairly assessed and for brewers to receive detailed feedback. Following the first British BJCP exam, there were qualified judges around, and judges need to be active in order to maintain their status. What I didn’t expect was that it would make me the point of focus for competitions in the UK, nor that I would have over 50 people asking me to organize BJCP courses and exams here so that they could qualify as judges!”

At first I felt a little apprehensive about the BJCP angle. I’m not a certified judge — I’ve had no formal beer tasting training — and I was flattered that my knowledge and experience was thought sufficient to exempt me from qualification. American culture takes these things very seriously, applying a thoroughness and rigour which to British eyes can seem a little, well, anally retentive. And in common with other US beer competitions like the World Beer Cup, the BJCP gives great weight to the principle of judging to style guidelines: currently the program recognises around 80 beer styles grouped into 23 major categories, each one defined by a detailed description of at least 500 words.

Perfectly good beers can be marked down if they fail to conform to these. A fellow judge – who was BJCP accredited – and I actually had an example of this during the competition, where a rather decent beer in one of our flights had clearly been entered in the wrong category by someone who hadn’t read the guidance properly. With some heavy heartedness we duly marked it down, though perhaps not as ruthlessly as we ought to have done.

While I appreciate that judging beers within style categories helps to establish a level playing field so like can be judged against like, I’ve long been uncomfortable with the straitjacket such a system might place on the creativity of brewers if too rigorously enforced. On the other hand, the categories cover a very broad range of possibilities so brewers should be able to find a place for even their most eccentric creations, in the catch-all ‘specialty beer’ category if nowhere else.

In the event I got used to speed reading the style guidelines, which helpfully include commercial examples considered to be within the specified style, and quickly got the hang of the detailed scoring. Although more complex than any other judging system I’ve yet used, I had to agree it helped give fair consideration to each beer.

Ali’s experience suggests home brewing’s place within the UK’s wider beer culture is at something of a turning point. “There are more home brewers, and more of them are moving away from beer kits and experimenting with new ingredients – quality products that weren’t available before, like imported hops from the US, New Zealand and Australia,” he says. “And although the crossover between professional and home brewing is not as developed as in the US, it’s growing.”

He’s certainly right on that last point. Britain has a mushrooming crop of microbreweries, and increasingly the people behind them come from outside the established industry. Some plunge straight into commercial brewing, often with the aid of an experienced business partner or consultant. But many come through home brewing, either by taking up brewing purely as a hobby and only later deciding to turn it into a business, or by using home brewing deliberately as a springboard to a commercial operation.

One of Britain’s highest achieving new brewers, Evin O’Riordan of the Kernel in London, is a good example of that last group. He returned from a stay in the US determined to become a working craft brewer, and honed his skills through home brewing, becoming involved with the Durden Park Beer Circle, a group of amateurs who dedicate themselves to recreating historic British recipes. Evin is a key figure in the London Brewers Alliance, the umbrella group for the capital’s multiplying craft breweries, where London Amateur Brewers is also represented. And recently one of Britain’s most outstanding micros, Thornbridge, has teamed up with pub chain Nicholson’s in an arrangement familiar in the USA, running a home brewing competition in which the prize is the chance to produce the winning beer commercially.

All these developments are to be welcomed. As I said above, home brewers brew what they like, and the influence of the home brewing aesthetic is one of the main reasons why US craft brewing today is so eclectic, dynamic and innovative. British brewing could make good use of the energy, creativity and love of the amateur, ensuring that the gap between the beer kit and the commercial micro is filled to everyone’s benefit.

Read a full list of winners at www.bristolhomebrewcompetition.org.uk. For more about the BJCP see www.bjcp.org.

There’s a blog piece about the event and more pics by Phil Lowry here: http://beermerchants.wordpress.com/2011/09/03/national-homebrew-competition-2011/

Enjoyed the article Des, long read! Reminds me to get onto Ali re the next exam in Brizzle

Great piece Des, thanks for the kind words about my amber and weizen 🙂

The most satisfying thing about homebrewing for me is when you’re able to share your brews with other beer enthusiasts, and they enjoy drinking it as much as you enjoy making it.

For homebrewers, remember that the London and SE festival is coming up on the 12th Nov. Check out the LAB website fire details.