In the early 1990s, as Czech brewing faced the new challenges and opportunities of the return of the free market, the trademark dispute between the USA’s biggest brewer Anheuser-Busch (AB) and South Bohemian brewery Budějovický (Budweiser) Budvar entered a new phase. The dispute, which had been running on and off for almost a century, centred on AB’s best-selling Budweiser brand and its attempts to stop Budvar using that same brand name on its own beer, even though the name derived from the Czech brewery’s home city.

In a rather misguided effort to drum up support in the UK, AB approached the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA), putting its case to several influential members including veteran beer writer and campaigner Roger Protz and CAMRA company secretary Iain Dobson. After the meeting, the CAMRA representatives were astonished to read a press release from AB claiming the organisation supported its case – completely the opposite of the impression they’d intended to give. Hastily, CAMRA put out its own corrective statement, and the ripples of the incident even reached to Prague Castle, with a copy of the statement faxed to dissident playwright turned president Václav Havel in support of an official government response. All in all it was something of a PR disaster for AB and heads, apparently, rolled.

The incident illustrates several extraordinary things about Budvar. First there’s that still unresolved trademark dispute, which has long since gone beyond the merely commercial and taken on national and international significance, widely interpreted in terms of a David versus Goliath parable that illustrates all that’s beastly about big industrial brewing. Then there’s the close links between Budvar and British beer campaigners, which go back a long way, despite the fact that the filtered, pasteurised and kegged products the Czech brewer exports to the UK are a long way from the approved definition of real ale.

The other thing most people with more than a passing interest know about Budvar is that, over two decades after the ending of the command economy in what was then Czechoslovakia, it remains a state-owned enterprise. This is despite numerous threats of privatisation down the years from pro-free market politicians, the most recent one fought off earlier this year. Privatisation and the trademark dispute are not unconnected. The latter would likely deter any commercial buyer other than AB’s successor AB InBev – now the biggest brewer in the world as well as in the USA – and the loss of the Budweiser brands to a foreign interest would be the near-inevitable outcome.

This unique social and political background added to my own interest when I was invited on a free trip to the brewery in České Budějovice in April 2012, part of my prize for winning a Budvar-sponsored award. I had some interesting travelling companions too – including longstanding brewery supporter Roger Protz himself, and Budvar UK’s veteran head of PR, Denis Cox, who has been associated with the beer since the days when pro-Soviet Communist Gustáv Husák ruled in Prague.

Visiting the brewery, and meeting its staff, it’s immediately striking how that social and political background is part of Budvar’s lived identity. Since 2005, the extensive site in an industrial suburb to the north of the city centre has boasted a glitzy, glass walled visitor centre that includes an extensive walk-through AV presentation on the history of the brewery.

Once you get past the Disneyfied depiction of Otakar II, the 13th century Přemysl king who founded the city, improbably quaffing golden beer from modern glassware, you’re plunged into the detail of the trademark dispute from its first rumblings in 1907. The climax of the presentation is a 20-minute parody spy thriller, lavishly shot in 3D, in which a secret agent hired by wicked men in expensive suits to collect evidence against Budvar ends up coming over to the Bohemian side.

And just in case you miss the point, a new domestic poster campaign features cartoon fantasy Slavic knights (above left), their armour collaged from various elements of brewery and city history, defending Budvar’s honour and reputation. “Saying No makes us what we are,” run the slogans. “No to selling our own name…No to moving production from České Budějovice…No to reducing the 90-day lagering period.”

There’s a subtext here identifying brand and nation. Despite its fame abroad, Budvar is not a huge seller at home, even in its own region. It’s currently third in the league table of Czech breweries, commanding only 6% of a domestic market dominated by Pilsner Urquell (Plzeňský Prazdroj) – but Urquell is owned by the US-South African group SAB-Miller which has notoriously streamlined traditional production techniques. SAB-Miller is linked to MolsonCoors which in April bought the second biggest Czech brewer, Staropramen, previously part of AB InBev. Heineken, meanwhile, owns the smaller Krušovice brewery. Budvar’s patriotic positioning is nothing new, as Czech nationalism played a role in the brewery’s foundation.

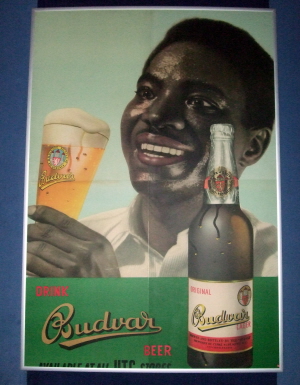

Past Budvar advertising on display at the visitor centre, though with no indication of what territory it was used in.

Though many of AB’s arguments over the years have been spurious, the US group has the shred of a case in being able to claim that it was using the name Budweiser before Budvar was. To understand the history, you need to know that the Czech lands were once part of Austria-Hungary, and until some rather unpleasant episodes of ethnic cleansing in the immediate aftermath of World War II, had a significant German speaking population. German was once the official language, and most place names have both Czech and German forms.

The biggest markets for Bohemian products were German-speaking so unsurprisingly German was favoured in commerce too. At the end of the 19th century the population of České Budějovice was more-or-less half German and half Czech, with Germans more predominant among privileged social groups. In German the city is known as Budweis, and the term ‘Budweiser’ is simply a regular adjective meaning someone or something from Budweis, so any beer brewed there could lay claim to it.

From 1385 citizens had the exclusive right to brew within the radius of a ‘mile’ from the city – actually around 10km – and from the end of the 15th century domestic brewing was gradually supplanted by a municipal brewery which at the end of the 18th century came under the collective control of the citizens. This ‘Burgher’s brewery’, also known as Budweiser Bürgerbräu or Budějovický měšťanský pivovar, was the first to market Budweiser beer widely as a brand – a golden lager that challenged another famous geographically designated Bohemian beer, Pilsner, from the city of Plzeň (Pilsen in German).

Such was Budweiser’s success and fame that in 1876 Adolphus Busch, one of a number of German-American brewing entrepreneurs who were to transform the beer market in the United States, introduced a beer named Budweiser at his Anheuser-Busch brewery in St Louis, Missouri. Positioning this beer as a premium brand, and claiming it was brewed using authentic Bohemian methods, AB staunchly protected its trademark, pursuing other US brewers who used the Budweiser name.

As people of German origin secured their dominance of US brewing, back in Bohemia German speakers increasingly found their social supremacy challenged. Industrialisation in towns like České Budějovice shifted the ethnic balance as the new labouring classes were largely made up of Czech-speaking people displaced from rural areas, boosting the potential for Czech-run businesses.

In 1895 a group of Czechs led by August Zátka founded a joint stock brewing company, originally known as the Český akciový pivovar (‘Bohemian joint stock brewery’), to challenge the German-dominated Bürgerbräu. Logically enough it also used the term ‘Budweiser’ to identify its beers, though in 1930 it registered the brand Budvar, one of those Orwellian contractions popular at the time, comprising the first syllable of the city’s name in both languages, and the last syllable of the Czech word pivovar meaning ‘brewery’.

Budvar crossed swords with AB when it started to export to the US, with AB making much of the fact that its own use of the term ‘Budweiser’ as a brand predated Budvar’s by almost 20 years. In 1911 the Bohemian brewer voluntarily waived its right to use the term Budweiser in the US in return for compensation. The breakup of Austria-Hungary and the creation of Czechoslovakia as an independent state following World War I meant the loss of a large and favourable market for Czech breweries, encouraging further efforts in more distant markets, and the dispute inevitably flared again in 1937. Two years later both Budvar and Bürgerbräu, under pressure from the US courts, agreed to avoid the term Budweiser in the USA.

A few months later the outbreak of World War II put an end to exports to anywhere but Germany. A Nazi-approved management ran the brewery from 1942, and on liberation in 1945 it was shut down. It shortly reopened as a nationalised industry under the post-war coalition government. From 1948, under the pro-Soviet communist regime, Budvar became part of a regional group but since this concentrated only on serving the domestic market and other parts of the Eastern Bloc like the German Democratic Republic, the AB issue fell quiet.

Then in 1966, the Czechoslovak government decided to increase its hard currency reserves with a concerted programme of exports to the West. Two breweries were chosen to participate – unsurprisingly given their famous names, these were Budweiser Budvar and Pilsner Urquell, and the former was reconstituted as a separate entity again.

Three variants of Budvar brands necessited by the trademark dispute with Anheuser Busch. Note the strong common visual identify, first developed in 1932.

The current international fame of both brands owes much to this bureaucratic decision of nearly half a century ago, ensuring they were already familiar to international audiences as the modern beer consumer movement emerged in the 1970s and 1980s. By using the brand Czechvar in North America, and hiding behind initials in the label details, Budvar got around the pre-war agreement with AB, but as that brewery too began to look to wider export markets, court cases followed in every country of the world where both brands aspired to have a presence.

In 1989 Husák’s government toppled alongside many others in the Warsaw Pact in the movement the Germans call die Wende. Czechs call it the sametová revoluce, the ‘velvet revolution’, and it was followed three years later by the ‘velvet divorce’ when the Czech and Slovak Republics became independent entities. Inevitably the changes heralded the return of the capitalist market and most previously state owned enterprises were ultimately privatised. Budvar, however, clung on in the public sector, and also flourished. As an exporting brewery it had emerged from the Cold War era in comparatively good shape, and under particularly skilful management it expanded still further, building on its international reputation to triple sales over a handful of years

But everywhere Budvar went, AB challenged it. A significant victory followed the Czech Republic’s entry into the European Union in 2004, when Budvar won the right to use the term Budweiser throughout the EU, obtaining Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) status in 2005. AB’s own application to use the term across the EU was rebuffed, with the result that while, for example, in the UK both breweries call their product Budweiser, in Germany only beers from České Budějovice are permitted to carry that label. Elsewhere AB has been more successful – in parts of the Far East, Budvar can use the Czech adjective Budějovický but not Budweiser.

The city’s other brewer has had rather more mixed fortunes – after decades of underinvestment prior to 1989, Budějovický měšťanský was privatised in the 1990s and despite some attempts at the export market, it has remained a small, local producer. Last year, in a complicated and rather dodgy deal, the business was split in two – one company owning the brewing assets, the other all the brands relating to the Budweiser name. The latter company was immediately sold to AB InBev, while the former ‘burghers’ brewery’ itself now makes beer exclusively under the Samson brand. This is the brewery that said Yes to selling its own name.

Budějovický Budvar managing director Jiří Boček explains his defiance of AB and the government at the brewery tap.

Budvar’s managing director Jiří Boček says that the messy situation around the trademark is undoubtedly one reason his enterprise has avoided privatisation. He also points out that thanks to the unique legal status it was given back in the 1960s, divesting the brewery could prove a lengthy and difficult process. It’s effectively a semi-autonomous operational arm of the Ministry of Agriculture, governed by a board appointed by the minister. It would first have to be converted into a limited company, which would require an act of Parliament signed by the President, inviting a public debate and a challenge by opponents.

Undoubtedly, however, one of the reasons why Budvar has been able both to remain in public ownership and to thrive in such unusual circumstances is down to Jiří Boček himself. Appointed in 1991, he has proved a shrewd and determined steward, and, at 54, has found himself something of a national hero. I meet him in the pleasant surrounds of the brewery tap, its vaulted ceiling and heavy wooden furniture retaining a traditional beer hall ambience despite recent refurbishment. He’s a big man, not at all loud but confident and focused, with an obvious charm.

He’s also a brewer. His father was a senior Budvar brewer, and he worked there himself as a chemist and brewer in the 1980s before promotion to his current post. He’s not a management wonk or a money man, and doesn’t have any particular sympathy with those that are. He’s generous to his old adversaries at the former Anheuser-Busch, whom he regards as fellow brewers, and scathing of the accountancy and management-driven regime that now presides at AB InBev. He also thinks that to cave in to that company’s demands would spell disaster for Budvar. “To build a new brand is much more expensive than to protect your existing key brand,” he tells me.

Mr Boček’s reluctance to deal with AB InBev (all his staff refer to him this way, so I will too) was one of the accustations against him levelled earlier this year by his government adversaries. The current centre-right coalition is ideologically committed to privatisation, and identified Budvar’s managing director as one of the obstacles to pursuing that agenda. His nominal boss, agriculture minister Petr Bendl, set out to discredit him with the support of certain sections of the media, pointing to his alleged autocratic style and lack of financial controls. Bendl threatened to pack the Budvar board with pro-government appointees, and to strike a deal with AB InBev behind the brewery’s back.

But the campaign backfired on a government under pressure from several other quarters and quite likely to lose the next election to parties that have stated they would keep the brewery in public ownership. A South Bohemian MP has even promised a referendum on Budvar’s future that, according to opinion polls, would certainly reject privatisation. Mr Boček acquitted himself well, winning public sympathy with persuasive appearances on television. As a result all future privatisations have been put on hold – not only for Budvar but for other remaining public undertakings like Czech Railways and Prague Airport.

To top it all, Budvar has just announced some excellent annual results, growing domestic sales by 3.4% and exports by 7.7%, a performance significantly better than the industry average, and increasing its surplus by 9.2%. As a public body it’s not in the business of making profits so surpluses are largely reinvested, but Mr Boček points out that like other breweries it pays beer duty and VAT, and also donates voluntarily to social projects, mainly in its own region.

We’re shown around the brewery by former head brewer Josef Tolár, who is now officially retired, but like several others I’ve met in similar positions, clearly unable to stay away from the place. Though Budvar is in many respects a big modern brewery currently turning out some 1.5million hl a year, several aspects of the production process are striking in their adherence to traditional practices and old fashioned ideas about quality. You can’t help but wonder what view a private firm with shareholders to please would take on some of this, especially one that happened to be the world’s biggest brewer.

Our first stop is at a pair of big white tanks storing water drawn from the brewery’s own 300m-deep artesian wells. All the water used – both brewing liquor and cooling and cleaning water – now comes from this source. Next up is the handsome 1985 brewhouse with gleaming copper-clad vessels set in a big white-tiled hall. There are two interconnected mash tuns that work together to provide the traditional decoction mash, a lauter tun and a kettle. Despite the relative newness of the kit, the brewhouse still uses open lautering, with hot wort from the mash tuns gushing from a line of taps into a trough that drains into the lauter tun. Josef invites us to taste this comfortingly malty liquid, which has a rounded sweetness still recognisable in the final product.

Retired Budvar head brewer Josef Tolár with one of the key ingredients, whole leaf Žatec (Saaz) hops.

Budvar once had its own maltings, but this has been replaced by an automated warehouse. Moravian pilsner malt is now the main malt used, with specially made coloured malt, also Moravian, for the dark beer. Another practice some brewers would regard as extravagant is the use of 100% Žatec (Saaz) whole leaf hops in the boil. Josef proffers a handful of the compressed leaves from a nearby sack – rubbed between the fingers, they have a beautifully fresh lemony scent. “You can drink beers made from whole hops all night,” he says. “Hop extract is too harsh. After half a litre the beer becomes undrinkable.”

The fermentation and conditioning vessels are all modern. The beer is fermented at a maximum temperature of 10°C in cylindroconicals, using a yeast culture that originally came from Bavaria in 1896. Examples of this are retained in the extensive yeast library at the Slovak Academy of Sciences in Bratislava, where it’s known simply as “Yeast strain number two”. The fermented beer then goes into big cylindrical tanks marshalled in the vast and chilly spaces of the lagering hall.

Wooden vessels were phased out in the late 1960s, though a few are still kept for show. With their great size and hefty locking systems, the old conditioning barrels look remarkably like some of the vessels used to mature lambic at the Boon brewery in Lembeek, and I’m reminded that some lambic brewers and blenders, such as De Cam, use oak barrels that formerly belonged to Pilsner Urquell.

There are no compromises on lagering periods. Budvar’s flagship beer, the standard 5% ABV světlý ležák 12°, spends 90 days in the tanks at a temperature of 2°C. Each tank holds around 3,700l and until a few years back there was capacity to mature 100,000hl at once. With sales growing, more capacity was needed. Many commercial brewers would have been tempted to increase throughput by slashing lagering times, but instead Budvar invested around Kč300m (£10m, €12m, $16m) in adding half as many tanks again. “We had good financial reserves,” says Josef.

The bottling line is highly automated, mainly with German equipment, and capable of getting through 40,000 bottles an hour. The snakes of full and empty bottles, and the robotic machines packing and lifting crates, are mesmerising to watch. During our visit, the line is on a run of Pardál, a more downmarket brand launched domestically in 2007 to compete with the likes of Urquell’s Gambrinus brand. One slight disappointment is the brewery’s preference for green glass for its custom embossed bottles, which affords the beer less protection. “It is for fashion and marketing,” says Josef. “Of course as a brewer I would prefer brown.”

Overall, it’s a glowing success story for a nationalised industry, enough to warm an old socialist’s heart – which I’m convinced is part of the reason Budvar is so appreciated in Britain. Many of the writers and campaigners that influenced CAMRA in its early years had left wing leanings, and wrestled with the contradiction of promoting a British industry dominated by the deeply Conservative ‘beerage’. The campaigners were generally not sympathetic to the one party state socialism of the Soviet Union and its allies, particularly after 1968 when Red Army tanks crushed the Czech liberalisation movement known as the Prague Spring. In the early 1970s Roger Protz was editor of the Trotskyist newspaper Socialist Worker, which carried the strapline “Neither Washington nor Moscow but international socialism” beneath its masthead. But in Czechoslovakia in the 1980s they discovered breweries making great beer without a profit motive. To a British socialist and beer fan, it must have seemed something of a dream come true.

“CAMRA always supported Budvar,” Roger tells me, “because it was a respectable beer.” During the 1980s it was imported in bulk through the Czech Ministry of Foreign Trade, and sent to Everards in Leicester for kegging. Back then, Denis Cox, now PR for Budvar UK, did a similar job for the Ministry, but there was no export department at the brewery itself or any direct communications with it. Roger himself first tracked the beer down to its source in the mid-1980s – he got a curious but friendly welcome and wasn’t allowed to visit the brewhouse. “Back then there was no domestic branding,” he recalls. “You went into a pub, asked for a pivo and took what you were given. You had to ask to find out if it was Budvar, Urquell or whatever.”

This was the decade when Britain’s own nationalised industries and public services created as part of the post-war Welfare State were being exposed to the ‘disciplines of the market’ under Thatcherist doctrine – in most cases to no obvious public benefit and with a notable amount of private profiteering. And while it was obvious that the Czech model wasn’t without problems and issues, including a chronic lack of investment, not to mention the viciously repressive regime that underpinned it, the rapacious capitalism that swept the former Eastern Bloc after 1989 would make the ‘fat cats’ that benefited from privatisation in Britain look modest and civilised in comparison.

But not at Budvar. It’s unclear how much the brewery’s status as a cause célèbre in Britain influenced its position at home. But it’s certainly helped the brand build credibility and a reputation for quality in its second biggest export market (the biggest is Germany, the third biggest Slovakia), and, through the international audience commanded by certain beer writers, in the rest of the English speaking world. The trademark story also appeals to those who instinctively side with the little man against the corporate bully.

It’s also interesting to consider how the view of Budvar as a nationalised industry through British eyes might differ from the local view. For over 40 years, all Czech industries were nationalised, but even before that, local communal arrangements for certain industries, the legacy of mediaeval modes of production, persisted far longer in the German sphere of influence than in the UK. It’s somewhat ironic that České Budějovice’s communal brewery, Budějovický měšťanský, has become the privatised sellout, while Budvar, with its roots firmly in the late Victorian era of entrepreneurial capitalism, is now the people’s champion.

That’s not to say Budvar doesn’t still make, in Roger Protz’s words, “respectable beer”. The flagship golden lager is marvellously easy going with a rich cracker-like malt, subtly balanced with hops, and particularly delicious in its unfiltered, unpasteurised kroužkovaný form. Easier drinking still is the underrated výčepní (4%), in the lower alcohol style known as desitka after its original gravity of 10° on the old Czech scale. More recently introduced are a rather decent dark, an alcohol-free beer and the liqueur-tinged strong lager Bud Premier Select (7.6%), originally aimed at the Russian market. The previously mentioned Pardál beers use hop extract rather than whole hops, selling at a cheaper price with their own very distinct branding.

But then Budvar competes in a marketplace where standards, despite the turmoil of the past quarter century, remain notably high. SAB-Miller’s rationalisation programme may have been ruthless, but even Pilsner Urquell, still regarded here as a premium brand, can provide a decent glassful, with a notably hoppy bite that might appeal more to contemporary tastes than the milder, less focused Budvar. Some of the smaller historic regional and local breweries in the Czech Republic make even more noteworthy beer, but don’t boast Budvar’s dramatic backstory and remain largely unknown outside the country. And there are an increasing number of modern, internationally-minded micros and brewpubs too. Josef Tolár tells me he welcomes these new arrivals and their eclectic influences. “Czech brewing has imported many good ideas from the West,” he says, before adding with a shrug, “and all the bad ones.”

Budvar seems safe for now, but privately some brewery staff still feel insecure. Along with many other Czechs, they have little confidence in governments of any shade not to sell the brewery out. As opinion polls show, few people here trust their politicians, exhibiting the wry cynicism you might expect from those who’ve experienced the transition from Stalinist repression to the get-rich-quick graft of the free market.

And when all’s said and done, it would be a great shame to see the brewery and its traditions fall to the mercies of AB InBev and the like. Despite its relative youth in historical terms, Budvar boasts a fine sense of place, its roots as deep in the soil of České Budějovice as those artesian wells. The city, the regional capital of South Bohemia, sits on the meandering Vltava (Moldau in German), the country’s longest river, around 125km upstream of Prague and close to some of the Republic’s most beautiful countryside. The city centre clusters attractively on a small island formed by two arms of the river. Cobbled streets wind from the riverside to a fine and expansive square, where grotesque gargoyles sprouting from the old town hall overlook graceful pastel-shaded baroque mansions.

It’s a great place to enjoy a glass of unfiltered Budvar, perhaps in the historic Masné Krámy, the old meat market that has long been a showcase Budvar pub. AB may have won a few courtroom arguments, but the absurdity of this beer not being able to call itself after the place where it’s made surely flies in the face of natural justice. Long may Budweiser Budvar continue to say No to selling its own name.

See also Roger Protz, ‘Bounced Czech: the plot to do down Budvar‘

Update 5 July 2012: Following a process that went all the way up to the European courts, AB InBev has recently been told again by the UK courts that it has to share the Budweiser trademark with Budvar in the UK. Read more.

Beer picks

The opinions expressed above, and any errors, are my own, but for background information I’d like to thank Denis Cox, Roger Protz, Evan Rail and Petr Samec, and Denis and Budvar for arranging the trip.

[…] The story of Budweiser Budvar (Des de […]